Stones of Contention: Native American Perspectives on America’s Monumental Divide

In the vast tapestry of American history, monuments stand as stoic sentinels, ostensibly marking significant events, venerating heroes, and preserving collective memory. Yet, for Native American communities, these towering figures and sculpted narratives often represent not shared heritage, but rather a painful reminder of conquest, erasure, and enduring injustice. The very ground beneath many of America’s revered historical monuments is shifting, as Indigenous voices increasingly demand a reckoning with the narratives they perpetuate, challenging a foundational understanding of national identity.

For centuries, the dominant historical narrative in the United States has largely marginalized or outright ignored the experiences of its First Peoples. Monuments, therefore, frequently serve as physical manifestations of this selective memory, glorifying figures who, from an Indigenous perspective, were architects of genocide, land theft, and cultural destruction. Christopher Columbus, the "discoverer" of America, is perhaps the most prominent example. While celebrated in mainstream culture with statues and holidays, for Native Americans, he symbolizes the brutal initiation of colonialism, slavery, and the decimation of Indigenous populations.

"These monuments aren’t just reminders of the past; they’re active participants in the ongoing erasure of our presence and the glorification of our oppressors," states Dr. Anya Redfeather, a prominent Indigenous historian and activist. "They teach a biased history that continues to harm our children and perpetuate harmful stereotypes. When we see a statue of a ‘pioneer’ or ‘explorer,’ we don’t see courage; we see the beginning of the end of our traditional ways of life, the forced removal, the broken treaties."

The issue extends far beyond Columbus. Consider the numerous monuments to figures like Andrew Jackson, whose Indian Removal Act led to the forced displacement of thousands of Native Americans on the Trail of Tears. Or the various tributes to U.S. cavalry officers and generals who led campaigns against Indigenous nations, often resulting in massacres. From a Native American viewpoint, these statues are not symbols of national pride, but rather a celebration of conquest, a constant re-traumatization that denies their humanity and historical suffering.

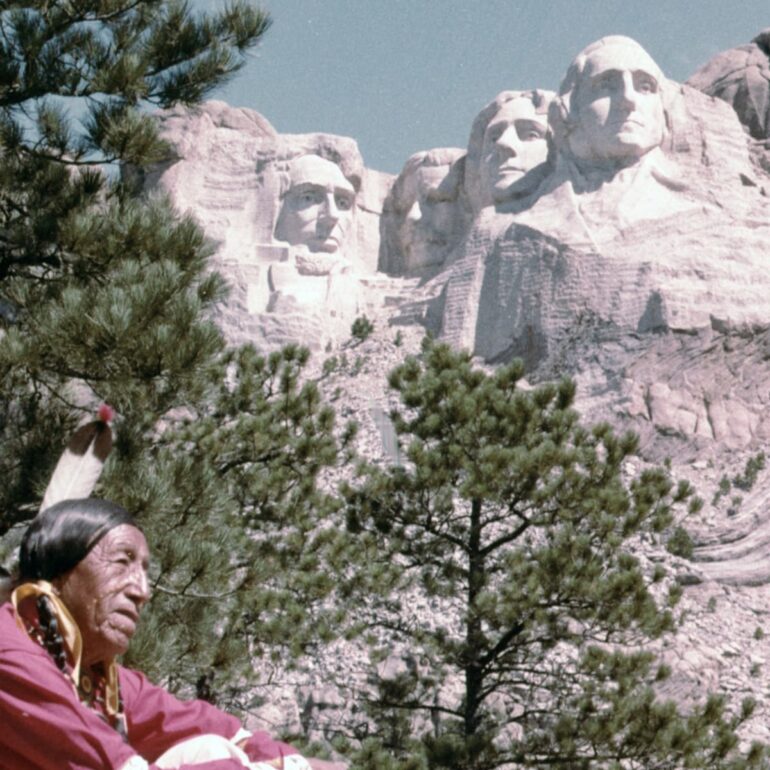

One of the most profound examples of this monumental divide is Mount Rushmore. Carved into the sacred Black Hills of South Dakota, land promised to the Lakota people in the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, it features the faces of four U.S. presidents: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln. For the Lakota, the monument is a permanent defacement of their sacred Paha Sapa, a holy site central to their spiritual identity.

"Mount Rushmore is a testament to broken treaties and the audacity of manifest destiny," says Elder Joseph Two Crows, a spiritual leader of the Oglala Lakota Nation. "They carved the faces of men who embodied the very policies that dispossessed us, on land that was stolen from us. It is an insult, a desecration that screams of triumph over our people, not a shared American heritage." The irony is stark: a monument celebrating American freedom and democracy, built upon the violation of Indigenous sovereignty and religious freedom.

The struggle over monuments is not merely about static stone and metal; it is deeply intertwined with the ongoing fight for land rights, cultural preservation, and self-determination. The land itself holds historical memory for Native peoples, often embodying their creation stories, ancestral journeys, and sacred ceremonies. A monument erected without Indigenous consent, particularly on stolen or sacred land, is therefore not just an aesthetic imposition but a spiritual violation.

Beyond the figures of conquerors, there are monuments that subtly perpetuate harmful narratives. The statue of "The Hiker" found in many American towns, honoring soldiers of the Spanish-American War, for example, often overlooks the war’s imperialist ambitions and its impact on Indigenous populations in the Philippines and Puerto Rico. Even seemingly innocuous historical markers can omit the Indigenous presence, creating a false narrative of empty lands awaiting European settlement.

The call for removal or recontextualization of these monuments is not an attempt to "erase history," as critics often contend. Rather, it is an urgent plea for a more complete, honest, and inclusive history. "It’s not about erasing history; it’s about completing it, making it honest," argues Sarah Many Arrows, a young Cheyenne activist. "Our history has been erased from public spaces for too long. We want a history that acknowledges the full story, the pain and resilience, not just the victor’s narrative."

This push for truth-telling has manifested in various ways:

-

Removal and Relocation: Many Indigenous groups advocate for the outright removal of statues of figures like Columbus or confederate generals (who, while not directly tied to Native American conflicts, represent a broader ideology of white supremacy and conquest that impacted all marginalized groups). Some have been successfully removed, such as the Columbus statue in cities like Philadelphia and Chicago, often replaced with monuments honoring Indigenous figures or symbols.

-

Recontextualization and Reinterpretation: In cases where removal isn’t immediately feasible or desired, calls are made to add interpretive plaques or digital exhibits that provide the Indigenous perspective. For example, at the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site in Colorado, the U.S. National Park Service has worked closely with descendants of the massacre to ensure their oral histories and perspectives are central to the site’s interpretation, offering a powerful counter-narrative to the initial U.S. Army accounts.

-

New Monuments and Public Art: A crucial aspect of this movement is the creation of new monuments that celebrate Indigenous heroes, cultures, and historical events. This includes erecting statues of figures like Sacagawea, Crazy Horse, or Tecumseh, or public art installations that tell Indigenous stories in contemporary ways. The Crazy Horse Memorial, still under construction in the Black Hills, stands as a direct counterpoint to Mount Rushmore, envisioned by Lakota Chief Henry Standing Bear as a tribute "to prove to the red man that the white man has a heart."

-

Indigenous Peoples’ Day: The growing movement to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day is a prime example of shifting focus from a figure of oppression to the celebration of Indigenous resilience and culture. Many cities and states have officially adopted this change, reflecting a broader societal recognition of the need for historical re-evaluation.

-

Educational Reform: Ultimately, the debate over monuments is a symptom of a larger educational deficit. Native American perspectives must be integrated into curricula from an early age, ensuring that future generations understand the complex, often painful, history of the continent. Only through comprehensive education can the public truly grasp why a statue might be a source of pain for one community and pride for another.

The journey towards reconciliation and a truly inclusive historical landscape is long and fraught with challenges. It requires empathy, a willingness to confront uncomfortable truths, and a commitment to shared responsibility. For Native Americans, the demand to re-evaluate historical monuments is not an act of erasing history, but an essential step towards healing, reclaiming their narratives, and asserting their rightful place in the ongoing story of America. Until the stones of contention reflect the diverse and often tragic histories of all its peoples, the monumental divide will continue to cast a long shadow over the nation’s promise of liberty and justice for all.