Sovereignty, Stewardship, and Scrutiny: The Complex Landscape of Native American Land Lease Agreements

By

On the sprawling, often starkly beautiful landscapes of Native American reservations across the United States, a quiet revolution is unfolding – or, perhaps more accurately, an ancient struggle is being re-negotiated. At its heart are Native American land lease agreements, a complex tapestry of commerce, sovereignty, history, and environmental stewardship. These agreements, which allow external entities to utilize tribal or individually allotted lands for purposes ranging from agriculture and energy development to housing and commercial enterprises, represent both a vital economic lifeline and a poignant reminder of centuries of land dispossession and federal oversight.

For many Native nations, land leases are a cornerstone of their economic development strategies, generating much-needed revenue for tribal governments and individual allottees, creating jobs, and fostering self-sufficiency. Yet, they are also fraught with historical baggage, bureaucratic hurdles, and the perpetual tension between economic expediency and the preservation of cultural heritage and environmental integrity. Understanding these agreements requires delving into a unique legal and historical framework that sets them apart from conventional real estate transactions.

A Legacy of Land Loss and Trust

The story of Native American land leases cannot be told without acknowledging the foundational injustice of land dispossession. Prior to European contact, Native nations held vast territories under communal stewardship. The subsequent centuries saw a dramatic shrinkage of these lands, culminating in the establishment of reservations and, crucially, the General Allotment Act of 1887 (Dawes Act). This disastrous policy sought to break up tribal communal lands, allotting individual parcels to Native Americans and declaring the "surplus" land open for non-Native settlement. The stated goal was assimilation; the actual outcome was the loss of two-thirds of the remaining Native American land base – approximately 90 million acres – by 1934.

The Dawes Act also introduced the concept of "trust land." Under this system, individual allotments and many tribal lands are held "in trust" by the U.S. federal government for the benefit of Native American tribes or individuals. This trust relationship, enshrined in law and upheld by Supreme Court decisions, means that Native lands cannot be alienated (sold) without federal approval, and are generally exempt from state and local taxation. While intended to protect Native lands, this system has also created a labyrinthine bureaucracy, primarily managed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), that often complicates simple transactions, including leases.

"The trust relationship is a double-edged sword," explains Professor Sarah E. Smith, an expert in federal Indian law. "It provides a layer of protection against outright land loss, but it also imposes federal paternalism that can stifle tribal self-governance and economic agility. Every lease agreement, even if negotiated directly by a tribe, ultimately requires BIA approval, a process that can be agonizingly slow and opaque."

The Mechanics of Modern Leasing

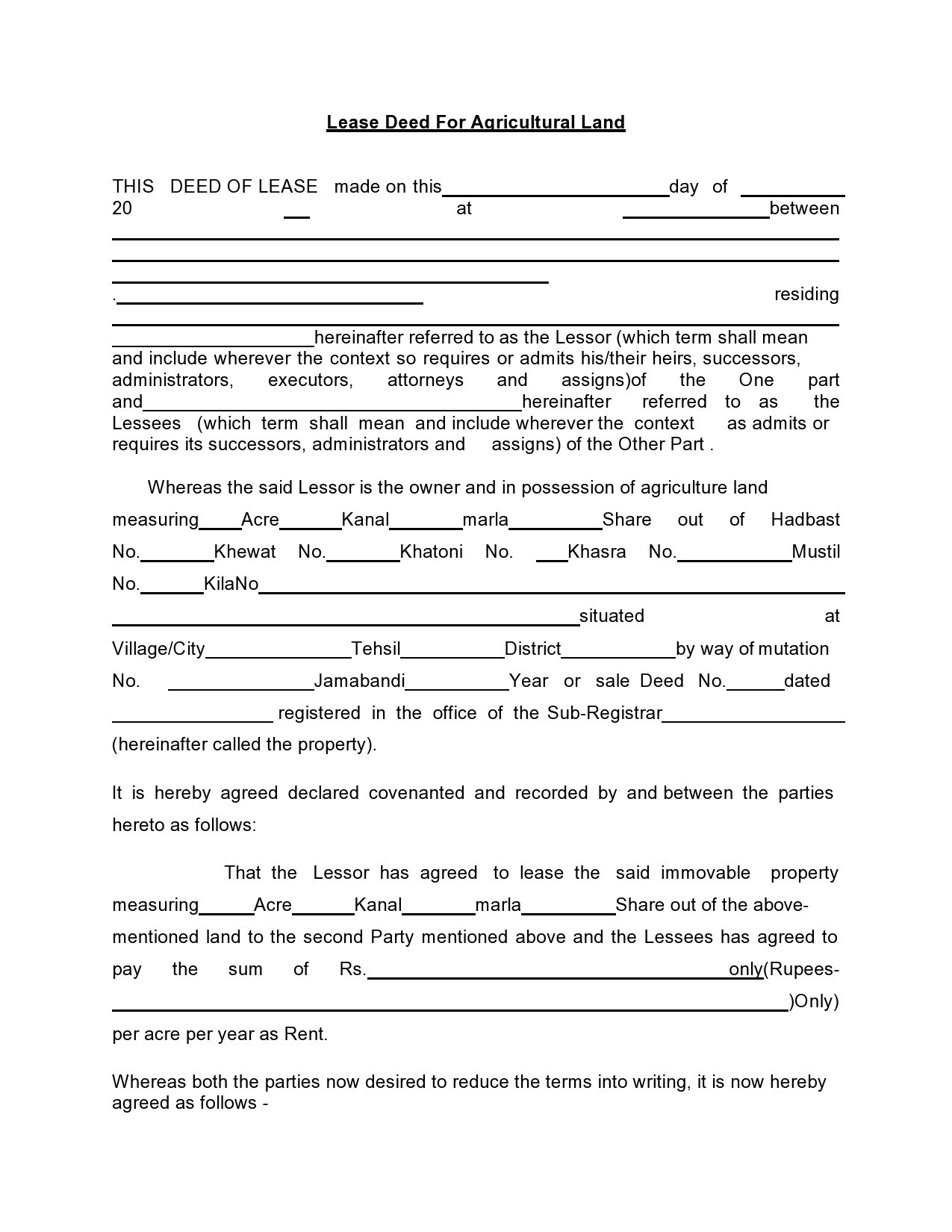

Today, land leases on Native American lands fall into two main categories: tribal leases (on lands owned by the tribe) and allotted land leases (on parcels owned by individual Native Americans, often with multiple co-owners due to heirship). The types of leases are diverse:

- Agricultural and Grazing Leases: Traditional and common, often for farming or livestock.

- Commercial Leases: For businesses, casinos, retail, and industrial facilities.

- Residential Leases: For homes, apartments, and planned communities.

- Energy and Resource Leases: For oil and gas extraction, coal mining, renewable energy (wind, solar), and mineral development.

- Infrastructure Leases: For roads, utilities, pipelines, and communication towers.

The negotiation process typically involves the prospective lessee (a company, individual, or government entity) working with either the tribal government or the individual allottees. For tribal lands, the tribal council or a designated tribal entity negotiates the terms, which can be extensive, covering rent, lease duration (often up to 25 years, with options for renewal, or up to 99 years for certain purposes under 25 U.S.C. § 415), environmental protections, job creation requirements, and cultural resource preservation clauses.

Once negotiated, the agreement must be submitted to the BIA for review and approval. This BIA oversight ensures compliance with federal regulations, protects the interests of the Native landowners, and verifies fair market value for the lease. While this process is meant to safeguard Native interests, it has historically been a source of frustration. "Waiting for BIA approval can hold up critical projects for months, sometimes years," laments Chairman Robert Manygoats of the fictional Black Mesa Nation. "In the business world, that kind of delay can kill a deal and cost our people jobs and revenue."

Economic Engines and Sovereignty in Action

Despite the bureaucratic hurdles, land leases are indisputably vital economic engines for many Native American communities. They provide a stable revenue stream that tribal governments use to fund essential services like education, healthcare, public safety, and infrastructure development. For individual allottees, lease payments can provide much-needed income in areas with limited employment opportunities.

The advent of renewable energy has opened new avenues for leasing. Many reservations are blessed with abundant sun and wind resources, making them ideal locations for solar and wind farms. These projects offer not only lease payments but also opportunities for tribal members to gain skills and employment in a growing industry. The Navajo Nation, for instance, has embraced solar development, leveraging its vast desert lands to generate clean energy and economic benefits.

"We are moving beyond simply being landlords," states a spokesperson for the Oglala Lakota Nation, discussing their wind energy aspirations. "These projects are about energy independence, creating our own power, and asserting our sovereignty over our resources. It’s about building a sustainable future for our children, not just for the next 25 years, but for the next seven generations."

Challenges and Persistent Tensions

However, the path to leveraging land leases is not without its significant challenges:

- Bureaucratic Delays and Inefficiency: The BIA’s approval process, while improving in some areas due to tribal self-governance initiatives, remains a frequent point of contention. The sheer volume of transactions and often understaffed BIA offices can lead to frustrating delays that undermine economic progress.

- Fair Market Value and Historical Undervaluation: Historically, Native lands have been undervalued in lease agreements. Ensuring that tribes and allottees receive fair market compensation is an ongoing struggle, requiring diligent negotiation and robust appraisal processes. The legacy of federal mismanagement of Native trust funds, famously highlighted in the Cobell v. Salazar lawsuit, underscores this historical pattern of financial exploitation.

- Environmental and Cultural Impacts: Resource extraction leases (oil, gas, coal) can bring substantial revenue but often come at a significant environmental cost, including water depletion, land degradation, and pollution. Tribes must carefully weigh these trade-offs, often balancing immediate economic needs with long-term environmental stewardship and the protection of sacred sites and traditional cultural properties. "Our land is not just dirt; it holds the spirits of our ancestors, our history, our ceremonies," emphasizes an elder from the Hopi Tribe. "Any development must respect that, or the cost is far too great."

- "Checkerboard" Ownership: Due to the Dawes Act and subsequent heirship, many reservations have a complex "checkerboard" pattern of land ownership, where tribal, allotted, and non-Native (fee simple) lands are interspersed. This creates jurisdictional headaches, complicates resource management, and makes unified development challenging.

- Capacity Building: Not all tribes have the internal capacity, legal expertise, or financial resources to negotiate and manage complex lease agreements effectively. Federal funding and technical assistance are crucial but often insufficient.

Towards Self-Determination and Sustainable Futures

The trend in recent decades has been towards greater tribal self-governance and self-determination. Under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, tribes can enter into contracts with the BIA to administer programs and services that would otherwise be run by the federal government. This includes taking on more direct control over land management and lease approvals, thereby streamlining processes and ensuring agreements better reflect tribal priorities and values.

Many tribes are investing in their own land departments, legal teams, and economic development corporations, empowering them to negotiate directly with prospective lessees from a position of strength and knowledge. This shift allows tribes to infuse their agreements with provisions that prioritize cultural preservation, environmental sustainability, local job creation, and long-term community benefits, rather than just short-term profit.

For instance, some tribes are incorporating language requiring lessees to employ a certain percentage of tribal members, to provide training, or to invest in tribal infrastructure. Others are developing comprehensive land use plans that guide development, ensuring that leases align with a holistic vision for the future of their lands and people.

Conclusion

Native American land lease agreements are far more than mere contracts; they are living documents that reflect a dynamic and evolving relationship between Native nations, the federal government, and the wider economy. They represent a continuous effort by Native peoples to reclaim control over their destinies, leverage their assets for the benefit of their communities, and uphold their responsibilities as stewards of their ancestral lands.

The challenges are formidable, rooted in centuries of injustice and complicated by bureaucratic inertia. Yet, the resilience, strategic vision, and inherent sovereignty of Native nations are increasingly shaping these agreements, transforming them from instruments of federal control into powerful tools for self-determination, economic prosperity, and the preservation of unique cultures and invaluable ecosystems. As the nation grapples with issues of resource management, energy transition, and equitable development, the lessons learned from the complex landscape of Native American land lease agreements offer a profound blueprint for a more just and sustainable future for all.