Echoes of Assimilation: Native American Boarding Schools, Historical Trauma, and the Enduring Spirit of Resilience

The phrase "Kill the Indian, save the man" is not merely a historical relic; it is a chilling mantra that once underpinned a devastating chapter in American history: the forced assimilation of Native American children through a system of federally funded and often religiously run boarding schools. For over a century, from the mid-19th to the late 20th century, these institutions systematically stripped Indigenous youth of their language, culture, and identity, leaving behind a legacy of profound historical trauma that continues to ripple through Native communities today. Yet, amidst this harrowing history, an equally powerful narrative emerges: one of extraordinary cultural resilience, a testament to the indomitable spirit of Indigenous peoples to reclaim their heritage, heal their wounds, and forge a future rooted in self-determination.

The origins of the Indian boarding school system can be traced to the post-Civil War era, a period marked by westward expansion and escalating conflicts between the U.S. government and Native nations. As military solutions proved costly and often ineffective, policymakers sought a new strategy to "civilize" and control Indigenous populations. Education, or rather, forced re-education, became the chosen instrument. Richard Henry Pratt, a former military officer and founder of the infamous Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania (established in 1879), articulated the philosophy with stark clarity: "All the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man."

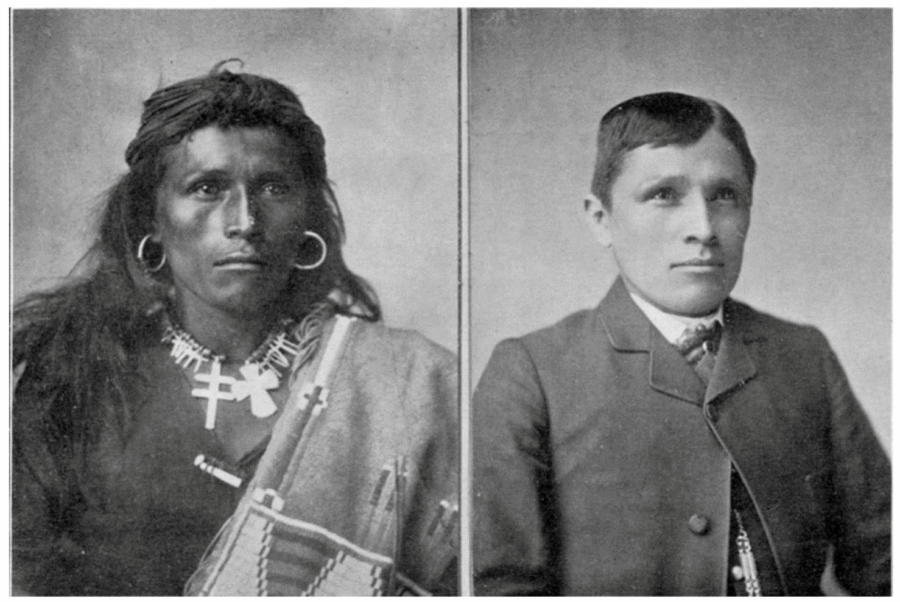

Under this directive, hundreds of thousands of Native American children, some as young as four or five, were forcibly removed from their families and communities. Often, parents had little choice, facing threats of withheld rations or imprisonment if they resisted. Upon arrival at the schools, children were subjected to a brutal regimen designed to erase their Indigenous identity. Their long hair, a sacred symbol in many cultures, was cut short. Their traditional clothing was replaced with uniforms. Their Native languages were strictly forbidden, punishable by severe physical abuse. They were given new, English names, and their spiritual practices were replaced with Christian doctrine.

Life within these institutions was harsh. Days were structured around military drills, vocational training (boys learned farming and trades, girls domestic skills), and academic instruction in English. However, the primary focus was not education in the modern sense, but rather manual labor and cultural obliteration. Disease, especially tuberculosis, was rampant due to poor sanitation, overcrowding, and inadequate nutrition, leading to tragically high mortality rates. Many children never returned home, buried in unmarked graves on school grounds, a grim discovery that continues to be made today.

Beyond the physical hardships, the psychological and emotional toll was immense. Children were isolated from their families and cultural support systems, often for years. They experienced profound loneliness, alienation, and a sense of displacement. Many endured physical, emotional, and sexual abuse at the hands of school staff. Survivors recount stories of beatings, solitary confinement, and constant humiliation for speaking their language or practicing their traditions. This systematic assault on identity and dignity left deep, festering wounds.

The long-term consequences of this systemic trauma, now recognized as intergenerational trauma, are staggering. Survivors often struggled with a fractured sense of self, unable to fully integrate into either the Native world they had been torn from or the white world they were forced into. Many returned home speaking English but no longer their Native tongue, creating communication barriers with their elders. They often lacked traditional parenting skills, having been denied the experience of being raised in a loving family unit, leading to cycles of neglect or abuse in subsequent generations. High rates of PTSD, depression, substance abuse, and domestic violence within Native communities have been directly linked to the historical trauma inflicted by the boarding school era.

A 2022 report by the U.S. Department of the Interior, initiated by Secretary Deb Haaland (the first Native American Cabinet Secretary), further illuminated the dark realities. The investigation identified over 400 federal Indian boarding schools across 37 states and found that the system was "a critical component of the United States’ strategy to assimilate Native Americans." The report detailed "rampant physical, sexual, and emotional abuse; disease; malnourishment; overcrowding; and a lack of health care." It also confirmed the existence of unmarked burial sites, underscoring the horrific human cost. Secretary Haaland stated, "The consequences of the federal Indian boarding school policies are tragically still with us today."

Yet, the story does not end with trauma. It is also a profound testament to cultural resilience. Despite the relentless efforts to eradicate their identities, Native peoples found ways to resist, adapt, and ultimately, to endure. Within the boarding schools themselves, children often formed secret bonds, speaking their languages in hushed tones, sharing stories, and finding solace in their shared heritage. These acts of quiet defiance kept cultural embers glowing in the darkest of times.

In the decades following the official closure of most boarding schools by the 1970s, Native communities embarked on a painstaking journey of healing and revitalization. The Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) of 1978, though currently under legal challenge, was a landmark piece of legislation aimed at preventing the unwarranted removal of Native children from their families and tribes, acknowledging the devastating impact of past policies.

Today, cultural revitalization efforts are flourishing across Indian Country. Language immersion schools and programs are working tirelessly to teach younger generations their ancestral languages, recognizing them not just as words, but as entire worldviews, repositories of knowledge and identity. "Our languages are the heartbeat of our nations," states Dr. LaNada War Jack (Shoshone-Bannock), an advocate for Indigenous rights. "To lose them is to lose a part of who we are, but to bring them back is to reclaim our very soul."

Traditional ceremonies, once practiced in secret, are now openly celebrated, bringing communities together in spiritual renewal and cultural affirmation. Arts, storytelling, and traditional ecological knowledge are being passed down from elders to youth, bridging the generational gaps created by the boarding school system. Tribal colleges and universities, founded and run by Native nations, are at the forefront of this effort, providing culturally relevant education that honors Indigenous knowledge systems while preparing students for contemporary challenges.

Healing circles, elder councils, and community-led initiatives are addressing the intergenerational trauma head-on, creating safe spaces for survivors and their descendants to share their stories, mourn their losses, and find collective strength. The "Road to Healing" initiative launched by Secretary Haaland is a vital step towards truth and reconciliation, providing a platform for survivors to share their experiences and for the U.S. government to acknowledge its role. Many look to Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) regarding its residential school system as a model for how a nation can confront its past and begin to heal.

The path forward is long and complex. It requires not only a full accounting of the past but also sustained investment in Native communities, support for language and cultural preservation, and genuine self-determination. It demands that the broader American public confront this uncomfortable history and understand its lasting impact. The scars of the boarding school era remain, etched into the collective memory and individual psyches of Native peoples. But alongside these scars is an undeniable and powerful force: the enduring spirit of resilience. It is a spirit that refuses to be silenced, that actively reclaims what was lost, and that continues to build a vibrant, culturally rich future, ensuring that the voices of their ancestors, once nearly extinguished, echo with strength and pride across the generations. The Native American nations, through their unwavering commitment to cultural survival, offer a profound lesson in the power of the human spirit to heal, reclaim, and thrive against all odds.