Sovereignty’s Enduring Struggle: Native American Advocacy for Treaty Rights

The echoes of promises made on parchment, often signed under duress and rarely honored, resonate through the landscapes of the United States. For Native American nations, treaties are not mere historical artifacts; they are living documents, the bedrock of their sovereignty, and the ongoing battle for their enforcement forms one of the most persistent and principled advocacy movements in modern American history. This struggle is a testament to resilience, a demand for justice, and a fundamental assertion of inherent nationhood that challenges the very foundation of colonial conquest.

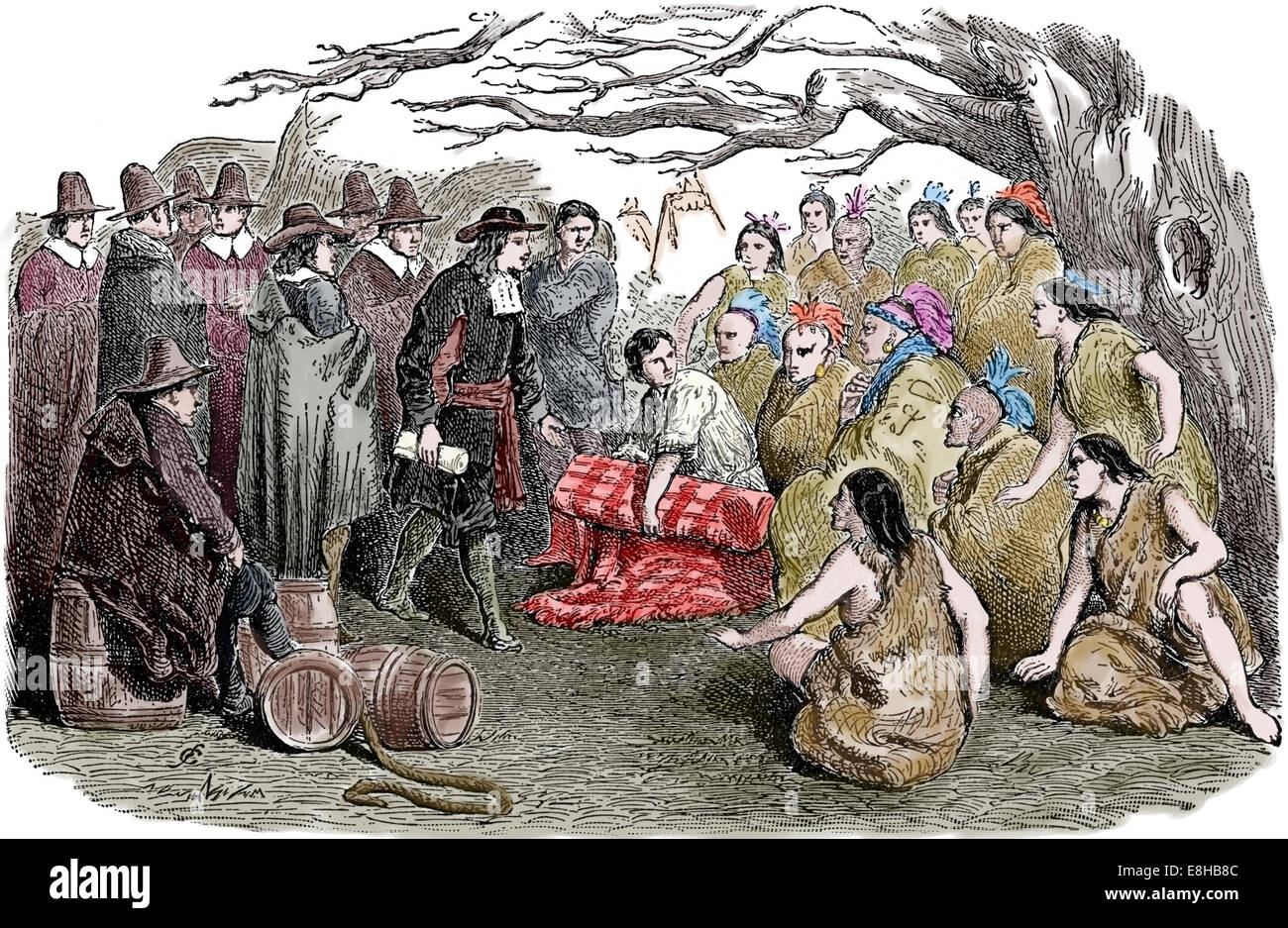

At its heart, Native American advocacy for treaty rights is a fight for self-determination. These treaties, numbering over 370 ratified by the U.S. Senate between 1778 and 1871, represent solemn agreements between sovereign nations. In exchange for vast tracts of land, Native tribes reserved specific rights – to hunt, fish, gather, govern themselves, and maintain their cultural practices on their remaining territories. The U.S. government, in turn, often pledged protection and services, establishing a "trust responsibility" to safeguard tribal assets and welfare. Yet, for centuries, these promises have been systematically broken, leading to land dispossession, resource depletion, and cultural erosion.

The historical trajectory of these violations is well-documented. Early treaties were often followed by forced removals, most infamously the "Trail of Tears" under the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which saw the Cherokee and other Southeastern tribes forcibly marched from their ancestral lands. Later, policies like the Dawes Act of 1887 aimed to break up communal landholdings into individual allotments, further eroding tribal sovereignty and facilitating the sale of "surplus" lands to non-Natives. The mid-20th century brought the "Termination Era," a policy designed to assimilate Native Americans by ending federal recognition of tribes and their trust relationship, leading to devastating economic and social consequences. Each of these policies, in its own way, was a direct assault on the spirit and letter of the treaties.

However, the late 20th century ushered in a new era of Native American self-determination, fueled by powerful legal challenges and grassroots activism. The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 marked a pivotal shift, allowing tribes to assume control over federal programs and services. This era empowered tribes to pursue their rights with renewed vigor, often turning to the very legal system that had historically been used against them.

Legal Battles: The Courts as a Battleground

The courtroom has become a crucial battleground for treaty rights, with landmark cases affirming tribal sovereignty and reserved rights. One of the most significant is Winters v. United States (1908), which established the "reserved rights doctrine." This case, involving the Fort Belknap Indian Community’s water rights in Montana, affirmed that when Congress created reservations, it implicitly reserved enough water to make the land productive. This doctrine has since been applied to other resources, asserting that tribes retain rights not explicitly relinquished in treaties.

Another monumental victory came with United States v. Washington (1974), often known as the "Boldt Decision." This case, brought by various tribes in Washington State, affirmed their treaty-reserved right to harvest up to 50% of the salmon and steelhead migrating through their traditional fishing grounds. Judge George Boldt famously ruled that the tribes had a right to take fish "at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations," in common with non-Native citizens, meaning an equal share. This decision was met with intense opposition and even violence from non-Native fishermen but was ultimately upheld by the Supreme Court. The Boldt Decision not only restored vital economic resources to tribes but also reaffirmed the "time immemorial" nature of their relationship with the land and its resources, challenging the notion that their rights were merely privileges granted by the federal government.

These legal victories underscore a fundamental principle: treaties are not grants of rights to Native Americans, but rather grants of rights from them, reserving what was not explicitly given away. As the late Native American scholar and activist Vine Deloria Jr. famously stated, "The treaties are not ancient documents… they are the living law of the land, as binding today as they were when they were signed."

Grassroots Activism: The Power of Collective Action

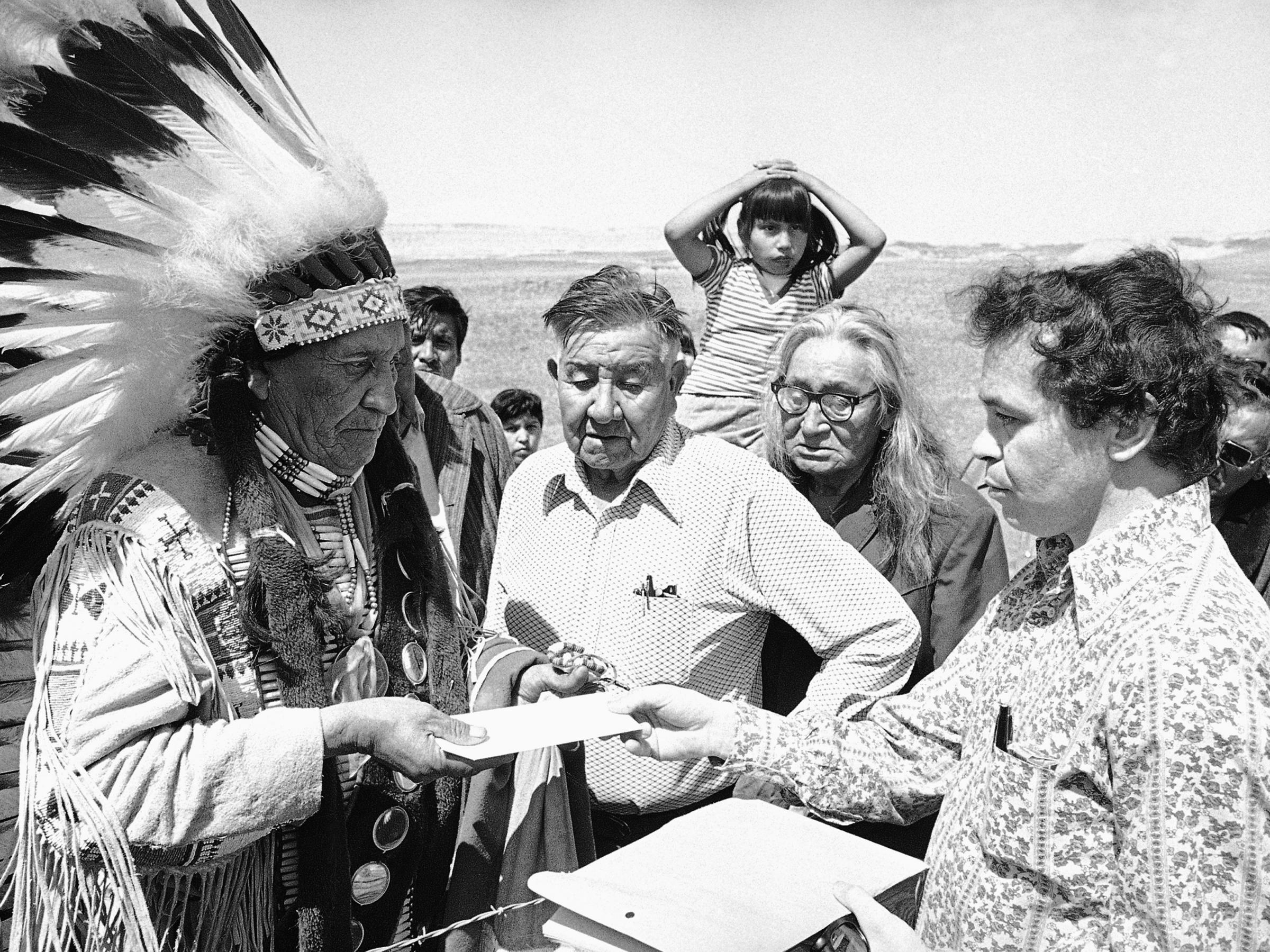

Beyond the courtroom, Native American advocacy for treaty rights thrives on grassroots activism and public protest, drawing national and international attention to ongoing injustices. The American Indian Movement (AIM), founded in 1968, played a crucial role in raising awareness and demanding federal accountability for treaty violations. Their occupation of Alcatraz Island (1969-1971) and the siege at Wounded Knee (1973) brought the issues of broken treaties, poverty, and self-determination into the national consciousness.

In more recent times, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s struggle against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) from 2016-2017 became a global symbol of treaty rights advocacy. The pipeline’s proposed route threatened sacred burial grounds and, more critically, the tribe’s primary water source, the Missouri River, which was protected by the Fort Laramie Treaties of 1851 and 1868. Thousands of "water protectors" from across the globe, including members of over 300 tribal nations, converged at Standing Rock, asserting "Mni Wiconi" – Water is Life. This movement highlighted the intersection of treaty rights with environmental justice and indigenous sovereignty, demonstrating the immense power of unified action and the deep spiritual connection Native peoples have to their ancestral lands and waters. While the pipeline was eventually completed, the advocacy forced significant legal battles and delays, and it galvanized a new generation of activists and allies.

The Federal Trust Responsibility and Its Failures

A cornerstone of treaty rights advocacy is the concept of the federal trust responsibility. This legal and moral obligation requires the U.S. government to protect tribal lands, resources, assets, and self-governance. However, the consistent underfunding of essential services like healthcare, education, and infrastructure in Indian Country is a direct failure of this responsibility. The Indian Health Service (IHS), for example, is notoriously underfunded, leading to health disparities that are a direct consequence of historical injustices and broken promises. Advocates continually push for adequate funding, arguing that these are not handouts, but rather the fulfillment of treaty obligations and the cost of lands ceded.

International Recognition and the Path Forward

Native American advocacy has also reached international platforms. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2007 (and endorsed by the U.S. in 2010), provides a universal framework for the rights of indigenous peoples, including their rights to self-determination, lands, territories, resources, and cultural integrity. While non-binding, UNDRIP offers a powerful tool for advocacy, allowing Native nations to hold their governments accountable to international human rights standards.

The future of treaty rights advocacy remains dynamic and multifaceted. It involves:

- Continued Legal Action: Challenging new infringements on land, water, and resource rights, often in the face of powerful corporate interests and state governments.

- Political Engagement: Lobbying Congress, state legislatures, and federal agencies for policy changes, increased funding, and respect for tribal sovereignty.

- Public Education: Dispelling myths and fostering a deeper understanding among the general public about the historical context, legal weight, and contemporary relevance of treaties. Many non-Native Americans are unaware of the existence or implications of these agreements.

- Cultural Revitalization: Protecting and promoting Native languages, ceremonies, and traditional ecological knowledge, which are inextricably linked to the lands and resources protected by treaties.

- Building Alliances: Forging coalitions with environmental groups, human rights organizations, and other marginalized communities to amplify their voices and broaden their impact.

The struggle for treaty rights is not merely about historical grievances; it is about the present and future well-being of sovereign nations. It is about ensuring that Native American communities have the resources, land base, and self-governance necessary to thrive, to protect their cultures, and to contribute to the rich tapestry of American society on their own terms. The perseverance of Native American advocates, against centuries of injustice, stands as a powerful testament to the enduring spirit of self-determination and the unyielding belief in the sanctity of nation-to-nation agreements. Their demand is simple, yet profound: Honor the treaties.