The Unfolding Narrative: How the National Museum of the American Indian Reclaimed a Voice

Nestled amidst the neoclassical grandeur of Washington D.C.’s National Mall, a structure of organic curves and earthy hues stands in striking contrast. The National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), a Smithsonian institution, is not merely a repository of artifacts; it is a profound declaration, a living testament to resilience, and a bold redefinition of how Native American cultures are presented to the world. Its very existence, and the journey that led to its 2004 opening, is a story steeped in a complex interplay of philanthropy, advocacy, cultural reclamation, and a fundamental shift in the power dynamics of museum curation.

The NMAI’s history begins not in the halls of Congress, but with the insatiable collecting passion of a single individual: George Gustav Heye. A wealthy New York financier, Heye began amassing Native American objects in the late 19th century with a zeal that, by today’s ethical standards, would be scrutinized, but which nonetheless resulted in an unparalleled repository of cultural heritage. From the early 1900s through the 1950s, Heye’s collectors scoured North, Central, and South America, acquiring an estimated 800,000 objects. In 1916, he established the Museum of the American Indian (MAI) in New York City, a private institution dedicated to his vast collection.

For decades, the MAI served as a significant, albeit problematic, resource. While it held an immense collection, its interpretative approach often reflected the prevailing anthropological viewpoints of the era – one of collecting and classifying cultures often perceived as "vanishing," rather than celebrating their enduring presence and vitality. The museum faced persistent financial difficulties and lacked the resources to adequately care for its collection or engage in modern exhibition practices. By the 1980s, the MAI was in crisis, its future uncertain.

This precarious situation, however, opened the door for a transformative opportunity. The Smithsonian Institution, America’s preeminent museum complex, recognized the collection’s immense value and the urgent need for its preservation. More importantly, Native American leaders and advocates saw a chance to fundamentally alter the narrative surrounding Indigenous peoples in a national institution. This wasn’t just about saving a collection; it was about finally establishing a museum by Native people, for Native people, and about Native people.

The negotiations were protracted and complex, involving the MAI’s trustees, the Smithsonian, and crucial input from Native American communities. A pivotal moment came with the passage of the National Museum of the American Indian Act by Congress in 1989. This landmark legislation established the NMAI as the 16th museum of the Smithsonian Institution and mandated the transfer of the Heye collection. Crucially, it also laid the groundwork for a new kind of museum – one that would operate with a strong commitment to Native American perspectives, self-determination, and active collaboration.

The Act was revolutionary in its vision. It wasn’t enough to simply house the objects; the museum was tasked with "advancing knowledge and understanding of the Native cultures of the Western Hemisphere through partnership with Native peoples." This commitment to partnership became the bedrock of the NMAI’s philosophy, setting it apart from virtually every other museum in the world at the time.

With the legislative framework in place, the physical manifestation of this vision began to take shape. The NMAI would have three distinct facilities: the main museum on the National Mall in Washington D.C.; the George Gustav Heye Center, housed in the historic Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House in New York City, utilizing the original MAI space; and the Cultural Resources Center (CRC) in Suitland, Maryland, a state-of-the-art facility dedicated to the care, study, and repatriation of the collections.

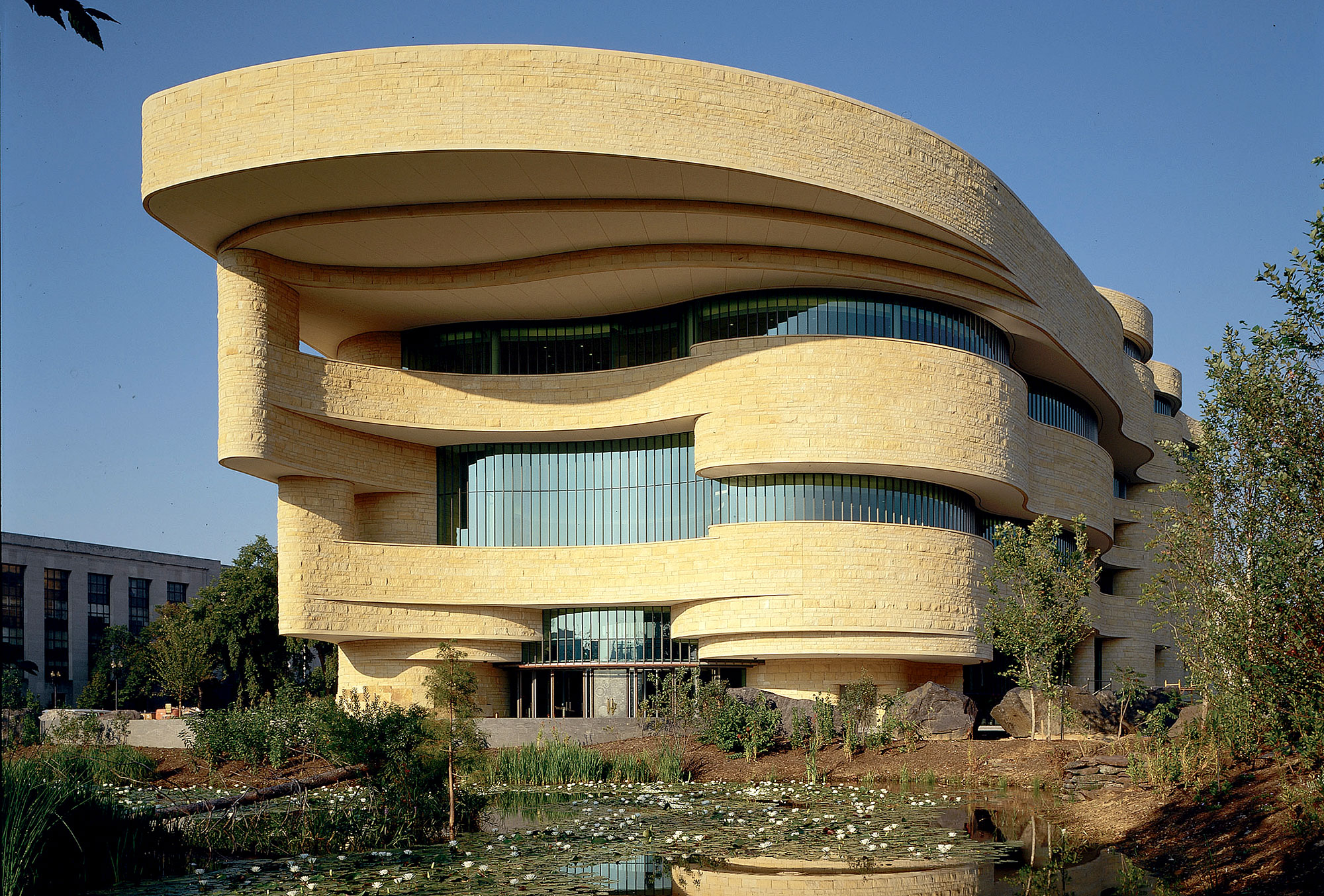

The design of the flagship museum on the Mall was itself a powerful statement. Architect Douglas Cardinal (Blackfoot), in collaboration with the design team, created a building that deliberately broke from the neoclassical tradition of its neighbors. Its curvilinear, wind-swept form, clad in Kasota limestone, evokes natural geological formations sculpted by wind and water. The building’s orientation is significant, facing east to greet the rising sun, and incorporating a grand entrance aligned with the four cardinal directions. Inside, a soaring central space, the Potomac Atrium, features a vast sky-lit dome, and natural light floods the galleries. A wetlands garden surrounds the building, integrating indigenous landscapes and plant life, further blurring the lines between architecture and environment. "The building is not just a building; it is a message," Cardinal once stated, emphasizing its role in representing the spiritual connection Native peoples have to the land.

The 2004 grand opening of the NMAI on the National Mall was an event of unprecedented scale and emotion. Tens of thousands of Native people from across the Western Hemisphere, joined by dignitaries and the public, participated in a "Return to the Homeland" procession, culminating in the museum’s inauguration. It was a moment of profound significance, signaling a homecoming for cultures long marginalized and often misrepresented.

However, the early years of the NMAI were not without their challenges. Crafting a new model of museum practice, one centered on collaboration and multiple perspectives, proved to be a complex undertaking. Some initial exhibitions, particularly the permanent ones, faced criticism for lacking a cohesive narrative or for being too focused on individual tribal stories without providing broader historical context. Critics, both Native and non-Native, pointed to a perceived lack of interpretive depth in certain areas.

W. Richard West Jr. (Southern Cheyenne and citizen of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes), the museum’s founding director, acknowledged these challenges as part of the learning curve for a truly groundbreaking institution. He famously articulated the NMAI’s mission as being "a museum of living cultures, not dead ones," underscoring the shift from static ethnographic display to dynamic cultural expression. The museum committed to an ongoing process of consultation, evaluation, and adaptation, continuously refining its approach to exhibition development and public engagement.

Over the years, the NMAI has evolved, strengthening its interpretive voice and deepening its commitment to indigenous self-representation. Its exhibitions now span a vast array of themes, from historical treaties and land rights to contemporary art, environmental stewardship, language revitalization, and the ongoing struggles for sovereignty and justice. Recent exhibitions, such as "Americans" (which explores the ubiquitous, yet often invisible, presence of Native American imagery in popular culture) and "Developing Stories: Native Photographers in the Field," demonstrate a sophisticated approach to engaging visitors with complex issues and showcasing Indigenous creativity.

A cornerstone of the NMAI’s philosophy is its commitment to "voice." Unlike traditional museums where curators typically dictate the narrative, NMAI actively involves Native communities in the development of exhibitions, programs, and educational materials. This collaborative model ensures that the stories told are authentic, nuanced, and resonate with the lived experiences of Indigenous peoples. This emphasis extends to its staff, with a significant number of Native professionals working across all departments.

The NMAI is also a vital center for education and cultural revitalization. It hosts numerous public programs, performances, film screenings, and symposia that provide platforms for Native artists, scholars, and community leaders. Its culinary program, the Mitsitam Cafe, celebrates indigenous foods of the Western Hemisphere, offering a taste of cultural heritage.

Beyond its physical presence, the NMAI plays a critical role in fostering understanding and challenging stereotypes. It serves as a powerful antidote to centuries of misrepresentation and erasure, offering a space where the richness, diversity, and enduring vitality of Native cultures are celebrated. It underscores that Native Americans are not relics of the past but vibrant, dynamic communities actively shaping the present and future.

The National Museum of the American Indian’s journey, from a vast private collection to a national institution of unparalleled significance, is a testament to the power of collective vision and the unwavering spirit of Native peoples. It is a museum that continues to challenge, educate, and inspire, proving that a museum can be more than a building of objects – it can be a beacon of self-determination, a forum for dialogue, and a living monument to the enduring narratives of America’s first peoples. Its history is still being written, one exhibit, one program, and one shared story at a time.