Echoes of the Longhouse: The Enduring Legacy of the Mohawk Nation

In the annals of North American history, few Indigenous nations have cast as long and influential a shadow as the Mohawk. As the "Keepers of the Eastern Door" of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, their strategic geographic position, formidable military prowess, and sophisticated political structure placed them at the epicentre of colonial power struggles for centuries. From their foundational role in forging a league of peace among warring nations to their modern-day battles for sovereignty and cultural revitalization, the Mohawk story is one of enduring resilience, adaptability, and an unyielding commitment to their identity.

The narrative of the Mohawk begins not with European contact, but with the profound vision of the Peacemaker, Deganawidah, and his disciple Hiawatha. Centuries before Columbus, these figures brought together the five warring nations – the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca – under the Great Law of Peace, forming the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. The Mohawk, known as the Kanien’kehá:ka (People of the Flint), were the easternmost nation, entrusted with defending the confederacy’s traditional territories and acting as its primary voice in dealings with outsiders.

The Great Law, or Kaianere’kó:wa, established a sophisticated democratic system that profoundly influenced later constitutional thought. It emphasized consensus, the equality of clans, and the empowerment of women as clan mothers who held ultimate authority over land and the selection of chiefs. "Our government was not by coercion," explains Mohawk elder Jake Swamp, "but by the consent of the governed, based on the principles of peace, power, and righteousness." This indigenous democracy, rooted in a spiritual understanding of interconnectedness, provided the Mohawk with a unified front and a clear sense of purpose long before the arrival of Europeans.

The 17th century heralded a dramatic shift in the Mohawk world. Their strategic location along the Mohawk River valley, connecting the Great Lakes to the Hudson River, made them invaluable trading partners and formidable adversaries for both the French and the Dutch, and later the English. The burgeoning fur trade became a double-edged sword: it brought wealth and European goods but also introduced devastating diseases and intensified conflicts, leading to the brutal "Beaver Wars" against neighbouring nations.

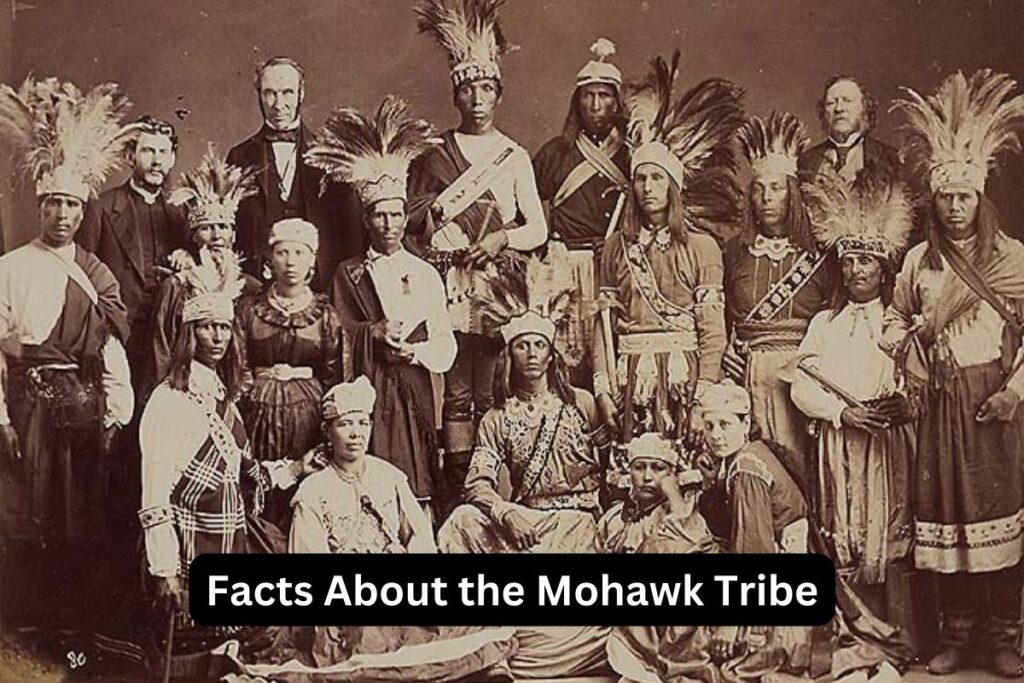

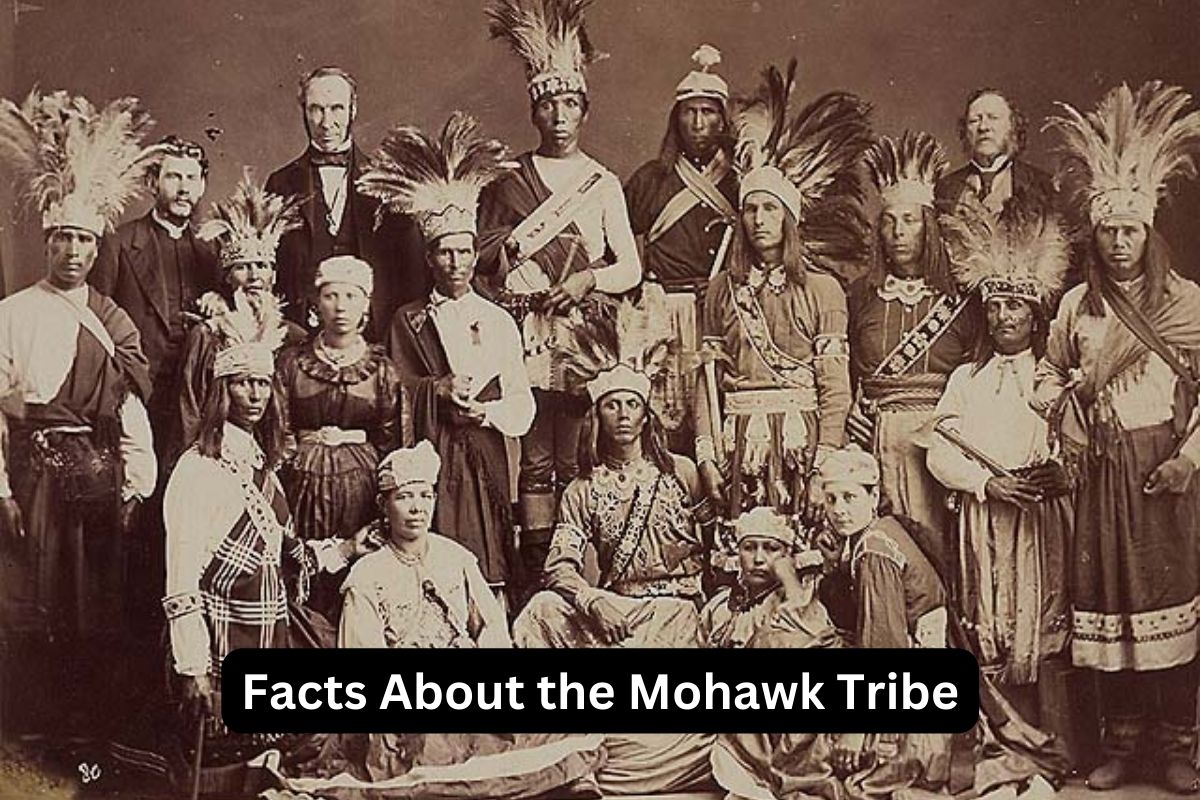

The Mohawk proved adept at playing European powers against each other. They forged a crucial alliance with the Dutch, providing furs in exchange for firearms, which enhanced their military dominance. When the English supplanted the Dutch, the Mohawk maintained their leverage, becoming indispensable allies to the British in the series of colonial wars that defined the 18th century. Their influence was so significant that the British crown often treated directly with the Confederacy, recognizing its sovereign status. Figures like Sir William Johnson, the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, formed deep relationships with the Mohawk, even marrying Molly Brant, a prominent Mohawk woman whose brother Joseph Brant would become one of the most celebrated and controversial figures in their history.

The American Revolution, however, proved to be the most divisive and devastating period for the Haudenosaunee. The Confederacy, committed to neutrality, was ultimately fractured by the conflict. The Mohawk, largely swayed by Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea), a brilliant military and political leader who had been educated by missionaries and had strong ties to the British, sided with the Crown. Brant argued that loyalty to the British was the best way to protect Mohawk lands and sovereignty from American expansion.

Brant led Mohawk and other Haudenosaunee warriors in numerous campaigns against the American revolutionaries. His ferocity and strategic brilliance made him a feared opponent. Yet, the outcome of the war was catastrophic for the Mohawk and their allies. Despite their loyalty and sacrifices, the Treaty of Paris (1783) between the British and the Americans ignored Indigenous land claims entirely. The Mohawk found themselves on the losing side, dispossessed of their ancestral lands in the Mohawk Valley.

"We were driven from our homes, and our hunting grounds," Brant lamented, "and we have been obliged to take refuge in the country of a foreign power." This displacement led to the establishment of the Six Nations of the Grand River Territory in Ontario, Canada, granted by the British Crown in recognition of their loyalty. Many Mohawk also settled at Tyendinaga and Akwesasne, straddling the modern US-Canada border, a testament to their fractured existence post-Revolution.

The 19th and early 20th centuries were marked by relentless pressure on Mohawk communities. Land cessions, assimilation policies, and the trauma of residential schools in Canada and boarding schools in the US sought to dismantle their culture and language. Yet, the Mohawk spirit of resilience refused to be extinguished. They adapted, finding new ways to assert their identity and sustain their communities.

One of the most remarkable examples of this adaptation is the Mohawk "skywalker" tradition. Beginning in the late 19th century, Mohawk men from communities like Kahnawake became renowned for their fearlessness and skill as high-steel ironworkers, helping to construct iconic skyscrapers and bridges across North America, including the Empire State Building and the Golden Gate Bridge. This dangerous profession, often performed without safety nets, became a source of pride and economic stability, allowing many to maintain their ties to their communities. It’s said that their comfort with heights stems from their ancient spiritual connection to the sky world, and their dexterity from generations of navigating dense forests. "We’re not afraid of heights," one Mohawk ironworker famously said, "we’re afraid of falling."

In the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st, the Mohawk Nation has been at the forefront of Indigenous rights and sovereignty movements. The Oka Crisis of 1990, a 78-day standoff between Mohawk warriors, Quebec police, and the Canadian military over the expansion of a golf course onto ancestral burial grounds near Kanesatake, became a watershed moment. It brought international attention to Indigenous land rights and the inherent sovereignty of First Nations. Though painful and violent, Oka galvanized Mohawk communities and served as a stark reminder that their fight for self-determination was far from over.

Today, Mohawk communities like Kahnawake, Akwesasne, and Tyendinaga continue to navigate the complexities of modern nationhood within colonial states. They are revitalizing their Kanien’kehá:ka language, establishing their own education systems, and asserting jurisdiction over their territories and resources. They are leaders in environmental stewardship, fighting against pollution and advocating for the protection of their traditional lands and waters. Economic initiatives, from gaming to technology, are pursued with the goal of self-sufficiency and communal well-being.

The Mohawk Nation’s historical role is not confined to the past; it is a living, breathing testament to the enduring power of Indigenous identity. From the wisdom of the Great Law of Peace that united nations, to the strategic acumen that shaped colonial geopolitics, to the modern battles for land and sovereignty, the Mohawk have consistently demonstrated an unbreakable spirit. Their story is a vital chapter in the larger narrative of North America, a powerful reminder of the deep roots and profound contributions of the continent’s first peoples, whose echoes of the longhouse continue to resonate with strength and resilience.