Modern Treaties on Turtle Island: Charting a New Course for Nationhood and Reconciliation

Across the vast and ancient landscapes of Turtle Island, a quiet revolution is unfolding, one negotiated clause at a time. Far from the battlefields of old, the modern treaty process represents a profound, albeit often protracted, effort to redefine the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Crown in Canada. These are not mere land settlements; they are constitutionally protected agreements that are reshaping governance, economies, and societies, offering a blueprint for a future built on recognition, rights, and respect. Yet, the path is fraught with challenges, marked by the weight of history and the complexities of forging nation-to-nation relationships within a colonial framework.

At its core, a modern treaty is a comprehensive land claims agreement and/or a self-government agreement. Unlike the historic treaties of the 18th and 19th centuries, often criticized for their coercive nature and subsequent misinterpretations, modern treaties emerged from the Indigenous rights movement of the latter half of the 20th century. They gained constitutional recognition with Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, which affirms existing Aboriginal and treaty rights. These agreements are designed to address the unfinished business of colonization, providing certainty over land and resources for all parties, while simultaneously empowering Indigenous nations to reclaim their inherent right to self-determination.

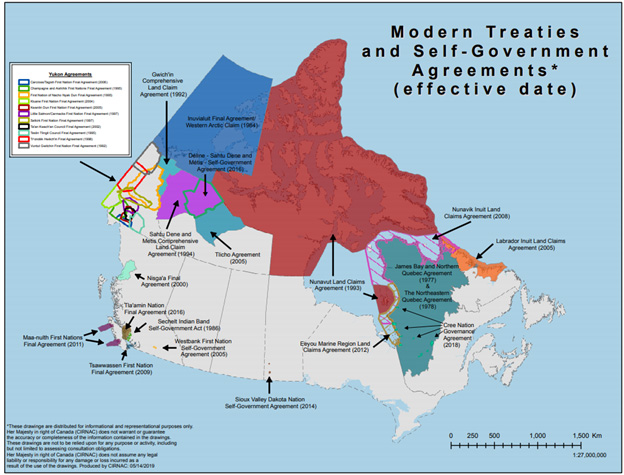

The genesis of modern treaty-making can be traced to landmark court cases, such as the 1973 Calder v. Attorney General of British Columbia decision, which legally recognized the existence of Aboriginal title in Canada. This pivotal ruling shattered the legal fiction of terra nullius (empty land) and forced the Crown to acknowledge that Indigenous peoples held pre-existing rights to their traditional territories. The subsequent Inherent Rights Policy adopted by the federal government in 1995 further solidified the commitment to negotiate self-government as part of these comprehensive agreements. Today, there are over 25 modern treaties in effect across Canada, covering significant portions of the landmass, from the Arctic to the Pacific.

The negotiation process itself is a labyrinthine journey, often spanning decades. It typically involves three principal parties: the Indigenous nation or nations, the federal government, and the provincial or territorial government. Each party comes to the table with distinct mandates, priorities, and historical perspectives. For Indigenous communities, the goal is often to restore a land base, establish self-government, secure economic opportunities, and protect cultural heritage. For the Crown, the objectives include achieving certainty over land and resource ownership, fostering economic development, and fulfilling legal and moral obligations to Indigenous peoples.

The sheer duration of these negotiations is a common point of contention. The Nisga’a Final Agreement, a seminal modern treaty in British Columbia, took 23 years to negotiate, from 1976 to 1998. The Tsawwassen First Nation Treaty, also in BC, took 15 years. This protracted timeline often strains the capacity of Indigenous communities, which typically have fewer resources than their government counterparts. "It’s a marathon, not a sprint," commented Dr. John Borrows, a leading Indigenous legal scholar, on the nature of these negotiations. "And too often, Indigenous nations are running it with fewer shoes and less water." The intergenerational commitment required means that many negotiators start and finish their careers, or even their lives, within the framework of a single treaty process.

What do these modern treaties entail? Their scope is vast and multifaceted:

- Land and Resources: Modern treaties define and transfer significant land parcels (fee simple or reserve-like lands) to Indigenous ownership. They often establish co-management regimes for traditional territories, granting Indigenous nations a powerful voice in environmental assessment, resource development, and wildlife management. This includes revenue sharing from resources extracted from their traditional territories.

- Self-Government: This is arguably the most transformative component. Treaties empower Indigenous nations to move beyond the confines of the Indian Act and establish their own laws and institutions. This can include jurisdiction over areas like education, health, social services, child welfare, justice, economic development, and cultural preservation. For example, the Nisga’a Nation now governs itself through the Nisga’a Lisims Government, with its own constitution, laws, and elected officials.

- Financial Components: Treaties typically include capital transfers and ongoing program funding, providing the financial resources necessary for Indigenous governments to operate and deliver services. This investment is crucial for economic development and nation-building initiatives.

- Cultural and Language Preservation: Many treaties include specific provisions for the protection and promotion of Indigenous languages, cultural practices, and heritage sites.

The impacts of modern treaties are tangible and far-reaching. The creation of Nunavut in 1999, Canada’s largest and newest territory, is a direct outcome of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement (1993). This monumental agreement provided the Inuit of Canada with political control over their homeland, fostering a vibrant Inuit-led government and economy. "Nunavut is a testament to what is possible when self-determination is recognized," states Aluki Kotierk, President of Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated, which represents the Inuit beneficiaries of the land claim. "It’s about our right to define our own future, guided by our values and our culture."

In British Columbia, the Maa-nulth First Nations Final Agreement (2011) and the Tla’amin Nation Treaty (2014) are examples of more recent agreements that offer significant economic opportunities and self-governance powers. These nations are now actively engaged in resource management, economic diversification, and the development of their own laws and policies, demonstrating a shift from dependency to self-sufficiency. "Our treaty isn’t just a document; it’s a living roadmap for our people," says Chief Councillor of the Tla’amin Nation, John Hackett. "It allows us to build a strong economy, protect our lands, and pass on our culture to the next generation, on our own terms."

Despite these successes, modern treaty-making is not without its critics and challenges. A recurring point of contention in earlier treaties was the concept of "extinguishment" of Aboriginal title, where Indigenous peoples were seen to be giving up their pre-existing rights in exchange for treaty benefits. While more recent treaties tend to use terms like "modification" or "definition" of rights, the debate over the ultimate scope of Indigenous sovereignty versus Crown sovereignty remains. Some argue that modern treaties are still fundamentally colonial in nature, serving to "settle" Indigenous rights rather than fully restore them, ultimately integrating Indigenous nations into the existing Canadian federal structure rather than allowing for true parallel sovereignty.

Implementation is another persistent hurdle. Once a treaty is signed, the real work begins. Disputes over interpretation, funding levels, and the pace of implementation are common. Governments can be slow to fulfill their commitments, leading to frustration and renewed legal battles. "A treaty is only as strong as its implementation," observes former National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, Perry Bellegarde. "We’ve signed these agreements in good faith, and now we need all parties to uphold their end of the bargain, every single time."

Furthermore, internal challenges within Indigenous communities can arise. The negotiation process can sometimes create divisions between those who support a treaty and those who believe it doesn’t go far enough, or that it compromises traditional ways of life. Ensuring that the voices of all community members, particularly elders and youth, are heard and reflected in the final agreement is a critical, ongoing task.

Looking ahead, the landscape of treaty-making continues to evolve. There is a growing emphasis on a "recognition and implementation" approach, moving away from a "claims" model that implies Indigenous rights are granted by the Crown. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which Canada has endorsed and committed to implement, is providing a new framework, emphasizing free, prior, and informed consent and the inherent right to self-determination. The future of treaty-making on Turtle Island will likely see more flexible, nation-to-nation processes that prioritize the affirmation of inherent rights and move towards genuine reconciliation, rather than merely settlement.

Modern treaties are imperfect instruments, born out of a complex and often painful history. They are not a panacea for all the challenges facing Indigenous peoples, nor are they the sole answer to reconciliation. However, they represent a significant and legally binding pathway forward. They are testaments to the resilience, determination, and enduring nationhood of Indigenous peoples, who continue to assert their rights and build self-sufficient communities on their ancestral lands. As these agreements continue to be negotiated, implemented, and refined, they will remain crucial documents in the ongoing story of Turtle Island, charting a new course towards a future where Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination are not just recognized, but truly flourish.