Modern Native American Tribal Governments: Structure, Powers, and Enduring Challenges

Often misunderstood and frequently overlooked in the broader American narrative, modern Native American tribal governments represent a unique and vital facet of self-determination within the United States. Far from relics of the past, these governments are dynamic, evolving entities exercising inherent sovereignty over their lands and peoples, navigating complex legal frameworks, and spearheading initiatives for economic development, cultural preservation, and social welfare. Their journey from colonial subjugation to contemporary self-governance is a testament to remarkable resilience, yet it remains fraught with significant structural, political, and socio-economic challenges.

At the heart of modern tribal governance lies the concept of inherent sovereignty. This is not a power granted by the United States government but rather a pre-existing authority that predates European contact. As the Supreme Court affirmed in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), Native American nations are "distinct, independent political communities, retaining their original natural rights." While subsequent federal policies, particularly during the allotment and termination eras, severely eroded this sovereignty, the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 marked a pivotal shift, encouraging tribes to re-establish formal governments and adopt constitutions. This act, often called the "New Deal for Indians," laid the groundwork for many of the governmental structures seen today.

The Structure of Self-Governance: Diverse Models, Shared Principles

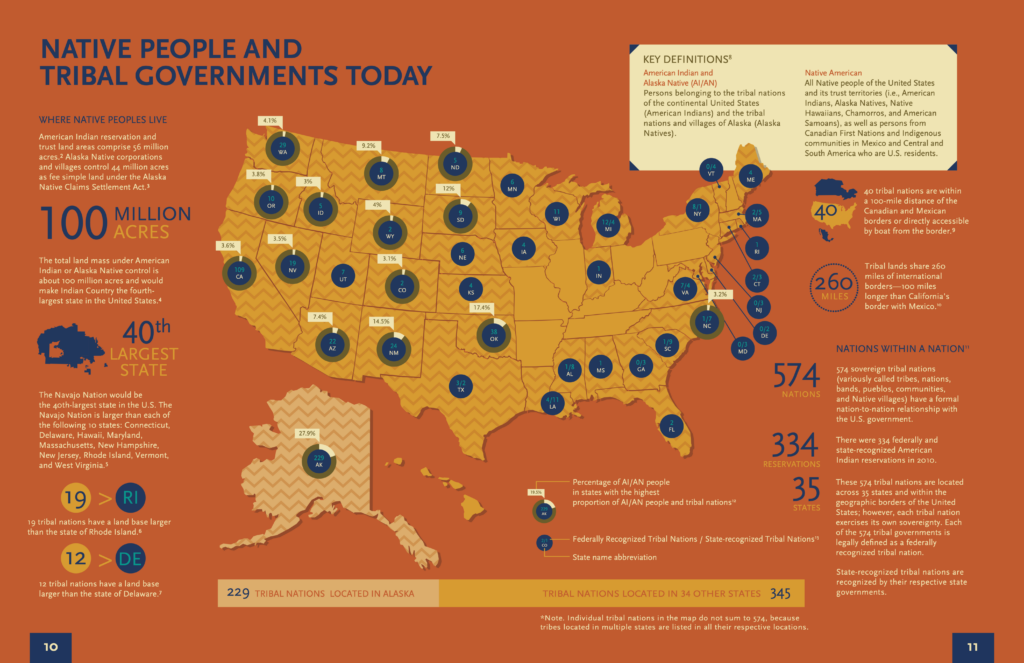

There is no single, monolithic structure for Native American tribal governments. Each of the 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States operates under a system tailored to its unique history, culture, and community needs. However, common organizational patterns prevail, largely influenced by the U.S. constitutional model of separation of powers.

Legislative Branches are typically the most prominent. Many tribes are governed by a Tribal Council or Business Council, composed of elected representatives. These councils act as the primary law-making bodies, responsible for enacting tribal ordinances, developing policies, approving budgets, and overseeing tribal enterprises. Some larger tribes, like the Navajo Nation, have a more extensive legislative body, such as the Navajo Nation Council, with numerous delegates representing distinct chapters or communities, making it one of the largest tribal legislatures in the nation.

Executive Branches are headed by officials such as a Tribal Chairperson, President, or Governor, often elected directly by tribal members. These executives are responsible for implementing council decisions, administering tribal programs and departments (e.g., health, education, housing, natural resources), serving as the principal spokesperson for the tribe, and engaging in intergovernmental relations with federal, state, and local entities. The specific powers of the executive can vary widely, from primarily ceremonial roles to being the dominant political force.

Judicial Branches consist of Tribal Courts, which are fundamental to upholding tribal law and resolving disputes. These courts have jurisdiction over civil matters arising on tribal lands and, crucially, over criminal offenses committed by tribal members. While federal law, notably Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe (1978), generally restricts tribal courts from exercising criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians, subsequent legislation like the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) reauthorizations in 2013 and 2022 have restored some authority for tribes to prosecute non-Indian perpetrators of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and trafficking on tribal lands. Many tribal court systems also incorporate traditional justice practices, emphasizing restorative justice, mediation, and community healing alongside Anglo-American legal principles.

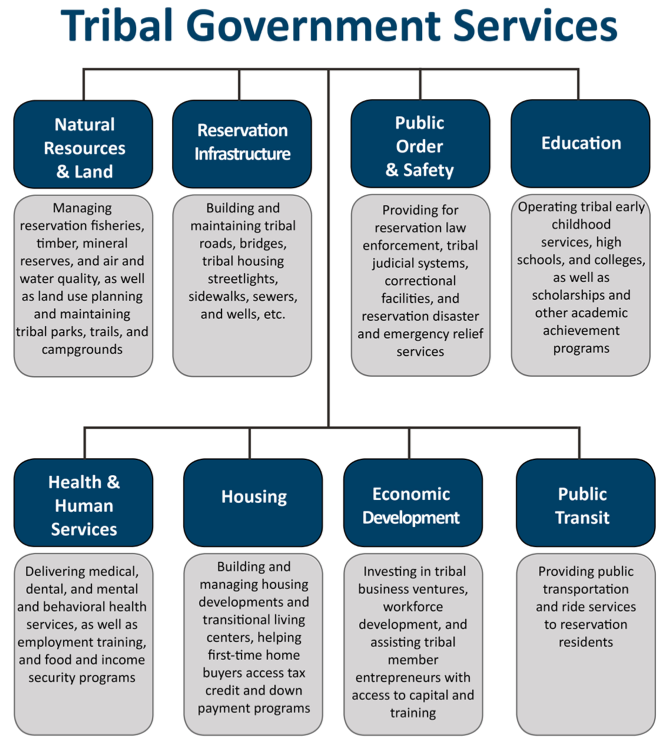

Beyond these core branches, tribal governments often establish numerous departments and enterprises, mirroring the services provided by state or local governments. These can include tribal police forces, fire departments, health clinics, schools, housing authorities, environmental protection agencies, and economic development corporations. Many tribes also have formal constitutions or governing documents that outline the powers and responsibilities of their government, define tribal membership, and protect the rights of their citizens.

The Scope of Tribal Powers: Exercising Sovereignty

The powers exercised by modern tribal governments are extensive and underscore their status as sovereign nations within the U.S. federal system.

Self-Governance and Internal Affairs: Tribes possess the inherent authority to govern their internal affairs, establish their own laws, determine their form of government, and manage tribal membership. This includes setting criteria for enrollment, which is a fundamental aspect of tribal identity and belonging.

Land and Resource Management: Tribal governments control vast land bases and their associated natural resources. This includes managing timber, water rights, mineral resources, and wildlife. Many tribes are at the forefront of sustainable resource management and environmental protection, implementing their own environmental codes that are often more stringent than federal or state regulations.

Law Enforcement and Justice: As noted, tribes maintain their own police forces and judicial systems to enforce tribal laws and resolve disputes. This includes civil jurisdiction over all persons, Indian and non-Indian, on tribal lands, and criminal jurisdiction over tribal members. The expansion of tribal criminal jurisdiction under VAWA demonstrates a continuing effort to strengthen tribal sovereignty in critical areas.

Economic Development: A significant power of tribal governments is their ability to foster economic development for their communities. This has famously included the establishment of gaming operations. The National Indian Gaming Commission reported gross gaming revenues of $40.9 billion in 2022, making tribal gaming a major economic driver that funds essential tribal services and infrastructure. Beyond gaming, tribes engage in diverse enterprises, including tourism, agriculture, energy production (oil, gas, renewable), manufacturing, and technology, generating revenue and creating jobs for tribal members and surrounding communities.

Taxation: Tribal governments possess the power to levy taxes on businesses operating within their territories and on tribal members. This includes sales taxes, property taxes, and excise taxes, further contributing to their economic self-sufficiency and funding for governmental services.

Provision of Services: Tribes are responsible for providing a wide array of social services to their members, including health care (often supplementing services from the Indian Health Service), education (operating tribal schools and colleges), housing programs, elder care, and child welfare services.

Cultural Preservation: A paramount power and responsibility is the preservation and promotion of tribal cultures, languages, and traditions. This involves funding language immersion programs, cultural centers, traditional arts initiatives, and protecting sacred sites and cultural patrimony.

Intergovernmental Relations: Tribal governments engage in nation-to-nation diplomacy with the U.S. federal government, state governments, and even international bodies. They negotiate compacts, treaties, and agreements, advocating for tribal interests and asserting their sovereign rights.

Enduring Challenges: A Complex Path Forward

Despite significant strides in self-determination, modern Native American tribal governments face a myriad of persistent and complex challenges.

The Legacy of Historical Trauma and Underdevelopment: Generations of forced removal, assimilation policies, boarding schools, and economic exploitation have left deep scars. This historical trauma manifests in disproportionately high rates of poverty, unemployment, substance abuse, mental health issues, and chronic diseases in many tribal communities. The lack of equitable access to education, healthcare, and economic opportunities continues to be a profound challenge.

Jurisdictional Complexities and "Checkerboard" Lands: The intricate web of federal, state, and tribal jurisdiction creates constant legal and practical hurdles. The "checkerboard" pattern of land ownership, a legacy of the allotment era, where tribal, individual Indian, and non-Indian lands are intermingled, complicates law enforcement, taxation, and land use planning. Disputes over water rights, mineral rights, and environmental regulations are common, often requiring lengthy and costly legal battles.

Chronic Underfunding of Federal Trust Responsibilities: The U.S. government holds a "trust responsibility" to Native American tribes, stemming from treaties and statutes. However, critical federal programs for health, education, housing, and infrastructure are consistently underfunded. The Indian Health Service, for example, receives only a fraction of the per-capita funding allocated to other federal healthcare programs, leading to significant health disparities. This forces tribal governments to stretch limited resources or rely on self-generated revenues, often from gaming, to fill essential service gaps.

Infrastructure Deficiencies: Many tribal nations, particularly those in remote areas, suffer from severe infrastructure deficits. Lack of access to reliable broadband internet, clean drinking water, adequate housing, paved roads, and modern utilities hinders economic development, education, and quality of life. The digital divide, for instance, prevents tribal members from accessing telemedicine, online education, and remote work opportunities.

Economic Diversification and Dependency: While gaming has been transformative for many tribes, it is not a panacea, and not all tribes have gaming operations or favorable market conditions. Over-reliance on a single industry can be risky. Challenges remain in diversifying economies, attracting non-gaming investment, and creating sustainable, high-wage jobs that address high unemployment rates.

Environmental Threats and Climate Change: Tribal lands are often disproportionately impacted by environmental degradation and climate change. Many communities face threats from rising sea levels, extreme weather events, drought, and the legacy of resource extraction and pollution. Protecting sacred lands and traditional ecological knowledge in the face of these challenges is a critical concern for tribal governments.

Cultural and Language Preservation: The ongoing struggle to revitalize and preserve endangered tribal languages and cultural practices remains a significant challenge. Decades of forced assimilation efforts have led to a decline in fluent speakers and traditional knowledge keepers. Tribal governments invest heavily in language immersion schools and cultural programs, but sustained funding and community engagement are vital for long-term success.

Internal Governance and Capacity Building: Rapid growth in tribal enterprises and government services can strain administrative capacity. Challenges include developing robust governance structures, ensuring transparency and accountability, managing complex budgets, and addressing internal political dynamics. Building a skilled workforce of tribal members to lead and staff these burgeoning governments is also a continuous effort.

Resilience and the Path Forward

Despite these formidable obstacles, modern Native American tribal governments exemplify extraordinary resilience, adaptability, and innovation. They are not merely recipients of federal aid but active, sovereign entities charting their own futures. From leading renewable energy projects and developing sophisticated telecommunications infrastructure to establishing culturally relevant educational institutions and advocating for justice on a global stage, tribes are demonstrating powerful self-determination.

The ongoing assertion of inherent sovereignty, coupled with strategic partnerships and innovative economic strategies, continues to strengthen tribal nations. Their journey is a powerful testament to the enduring spirit of Native American peoples and their vital role in the contemporary landscape of the United States, reminding the nation that true self-governance is not merely a right, but a dynamic, living reality.