Echoes in the Oaks: The Enduring History of California’s Miwok People

Beneath the golden hills and ancient oak groves of California, a history far deeper than the Gold Rush or Hollywood’s rise silently unfolds. It is a narrative etched into the very landscape, spoken in the rustle of leaves and the flow of rivers: the story of the Miwok people. For thousands of years, long before European sails dotted the Pacific horizon, the Miwok thrived across a vast swathe of what is now central California, their lives intimately intertwined with the land. Their journey, marked by profound connection, devastating loss, and remarkable resilience, offers a vital lens through which to understand the true heritage of the Golden State.

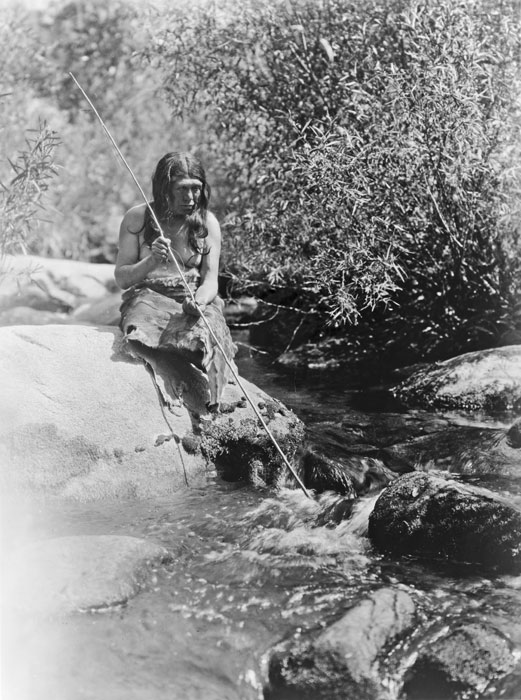

The Miwok, a linguistic family comprising several distinct groups—including the Coast Miwok, Lake Miwok, Plains Miwok, and various Sierra Miwok bands—were master adaptors to California’s diverse ecosystems. Their ancestral lands stretched from the Pacific coast, across the fertile Central Valley, and into the rugged foothills of the Sierra Nevada. This geographical spread allowed for a rich tapestry of subsistence strategies. The Coast Miwok, for instance, harvested shellfish, fished for salmon and steelhead, and hunted marine mammals, while their inland relatives relied heavily on deer, elk, and small game, complemented by an astonishing array of gathered plants.

At the heart of Miwok survival and culture was the acorn. Far from a simple nut, the acorn was the cornerstone of their diet, providing a staple carbohydrate source that supported dense populations. The process of preparing acorns was an intricate art, involving careful gathering, drying, cracking, grinding into flour, and then leaching out bitter tannins with water, often in sand basins. The resulting flour was then used to make a nutritious mush, bread, or soup. This sophisticated food technology allowed the Miwok to sustain themselves year-round and underscored their deep ecological knowledge. As ethnographer Samuel A. Barrett noted, the Miwok were "expert in utilizing the resources of their environment," demonstrating an intimate understanding of flora and fauna that sustained them for millennia.

Beyond sustenance, Miwok culture was rich with spiritual traditions, intricate social structures, and unparalleled artistry. Villages, often comprising several extended families, were led by hereditary chiefs and spiritual leaders. Basket weaving, in particular, reached an extraordinary level of sophistication and beauty. Miwok women crafted baskets of exquisite design and utility, using locally sourced materials like willow, sedge, and redbud. These baskets served every purpose imaginable, from cooking and storage to ceremonial use, and are today considered masterpieces of indigenous art. Storytelling, dance, and ceremony were also integral to their vibrant community life, connecting generations to their ancestors, the land, and the spiritual world.

The equilibrium of Miwok life began to unravel with the arrival of Spanish colonizers in the late 18th century. The establishment of missions like San Rafael Arcángel and San Francisco Solano, though primarily targeting coastal groups, gradually drew Miwok people into their orbit. Driven by disease, ecological disruption, and the promise of protection or sustenance, many Miwok were forcibly removed from their ancestral lands and compelled into the mission system. There, they faced forced labor, cultural suppression, and devastating epidemics of European diseases to which they had no immunity. The mission bells, intended to call converts to prayer, instead tolled for the rapid decline of indigenous populations and the erosion of a way of life that had endured for countless generations.

The transition from Spanish to Mexican rule, and then dramatically to American sovereignty in the mid-19th century, brought even greater calamity. The discovery of gold in 1848, ironically on Nisenan (Southern Maidu) land near Miwok territory, unleashed an unprecedented torrent of miners and settlers into California. The Gold Rush proved catastrophic for the Miwok and other indigenous peoples. Their lands, once carefully stewarded, were overrun, desecrated by mining operations, and summarily appropriated. Violence against Native Americans became rampant, often sanctioned by state and local authorities. Militias were formed, and bounties were even paid for "Indian scalps," driving the Miwok to the brink of extinction.

Treaties signed between the U.S. government and various California tribes, promising land and resources in exchange for peace, were largely unratified by Congress, leaving indigenous peoples landless and vulnerable. Survivors of the Gold Rush onslaught were often forcibly relocated to small, inadequate reservations or "rancherias," far from their traditional territories and spiritual sites. The population plummeted from an estimated 20,000-30,000 before contact to a mere fraction by the turn of the 20th century. The period was, in essence, an attempted cultural and physical genocide.

The subsequent decades of American policy continued to inflict harm through assimilationist practices. Native children were often taken from their families and sent to boarding schools, where they were forbidden to speak their languages or practice their cultures. The Dawes Act of 1887 aimed to break up communal landholdings into individual allotments, further eroding tribal cohesion and sovereignty. Despite these concerted efforts to erase their identity, the Miwok spirit endured. Hidden traditions, secretly practiced ceremonies, and the quiet passing down of language and stories within families kept the flame of Miwok culture alive.

The mid-20th century marked a turning point, spurred by the broader Civil Rights Movement and growing indigenous activism. Miwok communities, like many others, began a long and arduous fight for federal recognition, self-determination, and the restoration of their rights. The struggle was complex, often involving decades of legal battles to prove their continuous existence and cultural integrity to a government that had actively sought to deny it.

Today, the Miwok people are a vibrant testament to resilience. Federally recognized tribes like the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, the Tuolumne Band of Me-Wuk Indians, and the Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians, among others, are actively engaged in cultural revitalization. Language programs are bringing ancestral tongues back from the brink of extinction. Traditional arts, especially basket weaving, are experiencing a powerful resurgence, with new generations learning the intricate techniques passed down through millennia. Tribal governments are building economic enterprises, including casinos, to fund essential services, education, and healthcare for their members. They are also actively involved in environmental stewardship, leveraging their deep ancestral knowledge to protect and restore the lands and waters that are integral to their identity.

The Miwok story is not merely a chapter in California’s past; it is a living narrative. It speaks to the enduring connection between people and place, the devastating consequences of colonization, and the extraordinary strength of human spirit in the face of adversity. By acknowledging and honoring the Miwok people’s history, their continuing presence, and their invaluable contributions to the ecological and cultural tapestry of California, we begin to understand the true depth and richness of this land. Their echoes in the oaks remind us that California’s roots run far deeper than we often perceive, grounded in the ancient wisdom and unwavering resilience of its first peoples.