Echoes in Stone: Unraveling the Historical Tapestry of Mesa Verde’s Cliff Dwellings

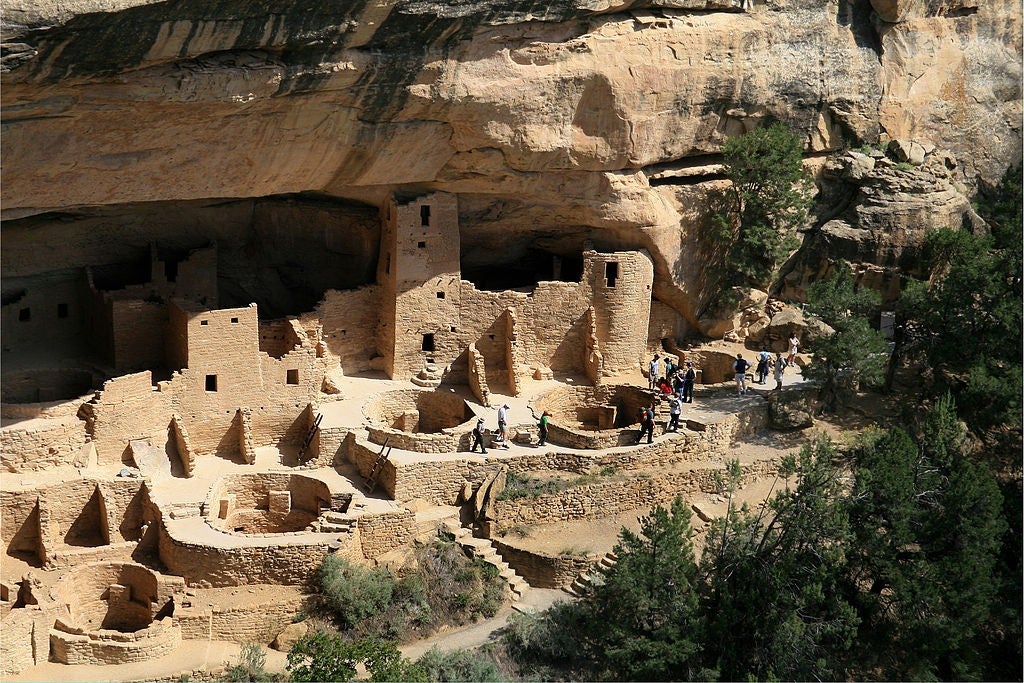

Perched precariously beneath the vast, cobalt skies of southwestern Colorado, the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde stand as a silent testament to a civilization both remarkably sophisticated and profoundly enigmatic. These architectural marvels, carved into the natural alcoves of the mesa, represent the zenith of Ancestral Puebloan culture, offering a window into a world that flourished for centuries before its mysterious abandonment. To understand Mesa Verde is to embark on a journey through time, tracing the evolution of a people, their ingenious adaptations to a challenging landscape, and the enduring questions surrounding their ultimate departure.

The story of Mesa Verde begins not with the iconic cliff dwellings, but much earlier, with the arrival of hunter-gatherer groups around 7,500 BCE. However, the Ancestral Puebloan culture, often respectfully referred to by this term instead of the Navajo-derived "Anasazi" (meaning "ancient enemy" or "ancestors of our enemies"), truly began to take shape around AD 450. These early inhabitants, known as the Basketmakers, were semi-nomadic, relying on foraging and hunting, but gradually began to cultivate maize, leading to a more sedentary lifestyle. Their dwellings were typically shallow pit houses, circular depressions in the earth covered with brush and mud, marking the initial steps towards permanent settlement.

As centuries passed, the Ancestral Puebloans of Mesa Verde underwent a remarkable cultural transformation, a process meticulously documented by archaeologists. By AD 750, during what is known as the Pueblo I period, they had transitioned from pit houses to above-ground, multi-room pueblos built from stone and adobe. These structures, often arranged in crescent shapes around communal plazas, signify a growing population and increasing social complexity. This period also saw significant advancements in pottery, with distinct black-on-white designs becoming prevalent, and the refinement of agricultural techniques, allowing for more extensive cultivation of corn, beans, and squash – the "three sisters" that formed the cornerstone of their diet.

The Pueblo II period (AD 900-1150) witnessed further aggregation, with larger villages and a more dispersed settlement pattern across the mesa top. It was during this time that the Ancestral Puebloans of Mesa Verde likely engaged in extensive trade networks, connecting them with distant cultures across the Southwest. While not on the scale of the monumental architecture seen at Chaco Canyon during this period, Mesa Verdeans were building larger, more organized surface pueblos, often with multiple stories, and developing sophisticated water management systems to capture and store precious rainwater.

However, it is the Pueblo III period (AD 1150-1300) that defines Mesa Verde in the popular imagination. Around AD 1200, a dramatic shift occurred: the Ancestral Puebloans began constructing their magnificent, elaborate dwellings not on the mesa tops, but within the natural alcoves and caves of the canyon walls. This was a monumental undertaking, requiring immense planning, labor, and engineering prowess. Why they chose to move into these precarious locations remains a subject of intense academic debate, though several theories prevail.

One prominent theory points to defensive needs. The cliff dwellings, accessible only by arduous climbs and hidden from the mesa top, offered inherent protection against potential raiders. Their strategic placement provided clear lines of sight across the canyons, allowing inhabitants to spot approaching threats from afar. "The construction of these dwellings in such inaccessible locations speaks volumes about the perceived need for security," notes archaeologist Dr. Steven Lekson, "whether from external enemies or internal strife."

Another compelling argument centers on environmental factors. The overhanging cliffs provided natural shelter from the elements, offering cooler temperatures in the scorching summer and warmer conditions in the harsh winter. The rock overhangs also protected the adobe and stone structures from direct rain and snow, ensuring their longevity. Furthermore, the south-facing alcoves, favored for many of the largest dwellings, maximized passive solar heating in winter while providing shade in summer, demonstrating an astute understanding of microclimates.

The sheer scale and complexity of these structures are awe-inspiring. Cliff Palace, the largest and perhaps most famous, boasts over 150 rooms and 23 kivas, housing an estimated 100 people. Balcony House, with its intricate system of tunnels and ladders, and Spruce Tree House, the third-largest and remarkably well-preserved, further showcase the ingenuity of their builders. These were not mere shelters; they were meticulously planned communities, complete with living quarters, storage rooms, ceremonial kivas, and communal plazas.

Life within these cliff dwellings was a delicate balance of communal living, hard work, and spiritual devotion. Agriculture remained the bedrock of their existence. Women and men worked together to cultivate corn, beans, and squash on small plots atop the mesa, or on narrow terraces along the canyon walls. Water, a perennial concern in the arid Southwest, was collected through ingenious systems of check dams, reservoirs, and seep springs, carefully channeled to their fields and storage vessels. Their diet was supplemented by wild game, gathered nuts, berries, and medicinal plants.

Craftsmanship flourished. The Ancestral Puebloans were master potters, producing beautifully decorated utilitarian and ceremonial wares. They wove intricate cotton textiles, crafted tools from stone and bone, and adorned themselves with jewelry made from shells, turquoise, and other precious materials obtained through extensive trade networks. Their advanced knowledge of astronomy is evident in the alignment of certain structures with solstices and equinoxes, suggesting a deep connection to celestial cycles for agricultural and ceremonial purposes.

At the heart of every Ancestral Puebloan community was the kiva – a circular, subterranean chamber that served as a sacred space for religious ceremonies, community meetings, and possibly male initiation rites. The kiva was a symbolic representation of the cosmos, connecting the physical world with the spiritual. Its central fire pit, ventilation shaft, and sipapu (a small hole in the floor symbolizing the emergence point of their ancestors from the underworld) were integral to their spiritual practices. The presence of numerous kivas within each dwelling underscores the profound role spirituality played in their daily lives.

Yet, despite their apparent mastery over their environment and the flourishing of their culture, by the end of the 13th century, Mesa Verde was abandoned. The Great Drought, a prolonged and severe dry spell recorded by tree-ring data from 1276 to 1299, is widely cited as a primary contributing factor. This relentless drought would have decimated crops, depleted water sources, and severely strained resources, making sustained life in the region increasingly difficult.

However, archaeologists and historians emphasize that the abandonment was likely a complex interplay of factors, not just a single event. Resource depletion due to centuries of intensive agriculture and logging for construction, coupled with population growth, could have led to environmental degradation. Social and political unrest, perhaps fueled by resource scarcity or internal conflicts, may also have played a role. "The decision to leave was likely not a sudden one, but a culmination of mounting pressures," explains one park interpretive sign, "forcing a collective choice for survival."

The Ancestral Puebloans did not simply vanish; they migrated. They moved south and east, eventually settling in areas that offered more reliable water sources, contributing to the formation of the modern Pueblo communities of Arizona and New Mexico, such as the Hopi, Zuni, and Rio Grande Pueblos. These descendant communities maintain a deep spiritual and cultural connection to Mesa Verde, viewing it not as a lost city, but as an ancestral homeland.

For centuries after their departure, the cliff dwellings lay silent, known only to local Ute and Navajo tribes. It wasn’t until the late 19th century that they were "rediscovered" by European Americans. In 1888, local rancher Richard Wetherill and his brother-in-law, Charlie Mason, stumbled upon Cliff Palace while searching for stray cattle. Their accounts sparked widespread interest, leading to a flurry of archaeological exploration, most notably by the Swedish scholar Gustaf Nordenskiöld, who meticulously documented and photographed many of the sites but also controversially shipped a large collection of artifacts back to Sweden.

The immense historical and cultural significance of Mesa Verde quickly became apparent, prompting calls for its protection. In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt signed legislation establishing Mesa Verde National Park, making it the first national park created to preserve the works of humans rather than natural wonders. In 1978, it was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, further cementing its status as a place of global importance.

Today, Mesa Verde continues to be a vibrant center for archaeological research, offering endless opportunities to learn more about the Ancestral Puebloans. The park serves as a powerful reminder of human ingenuity, resilience, and adaptation. It challenges us to consider the delicate balance between human societies and their environment, and the profound impact of climate change.

As visitors gaze upon the silent, stone structures clinging to the cliffs, they are not just looking at ancient ruins; they are encountering the echoes of a vibrant civilization. The whispers of the wind through the canyons carry stories of families, ceremonies, daily struggles, and enduring faith. Mesa Verde is more than a historical site; it is a sacred landscape, a place where the past reaches out to touch the present, inviting us to reflect on our own place in the grand tapestry of human history and our shared responsibility to protect its invaluable legacy.