Sentinels of Cedar: Unraveling the Profound Meanings of Native American Totem Poles

For centuries, along the mist-shrouded coastlines and dense forests of the Pacific Northwest, towering sentinels of cedar have stood guard. These are the totem poles, magnificent sculptures carved by the Indigenous peoples of the region, each one a testament to artistry, heritage, and a profound connection to the natural and spiritual worlds. Often misunderstood as mere decorative objects or, more egregiously, as religious idols, totem poles are, in fact, intricate visual archives – living documents that chronicle lineage, history, myths, and social structures. To truly appreciate their grandeur is to delve into the rich tapestry of cultures that brought them to life.

The tradition of carving monumental cedar poles is deeply rooted in the societies of the First Nations of British Columbia, Canada, and the Indigenous peoples of Alaska, Washington, and Oregon in the United States. Tribes such as the Haida, Tlingit, Tsimshian, Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwakiutl), Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka), and Gitxsan are renowned for their distinct styles and elaborate carvings. These are not relics of a forgotten past; totem poles remain a vibrant and evolving art form, echoing the resilience and enduring spirit of their creators.

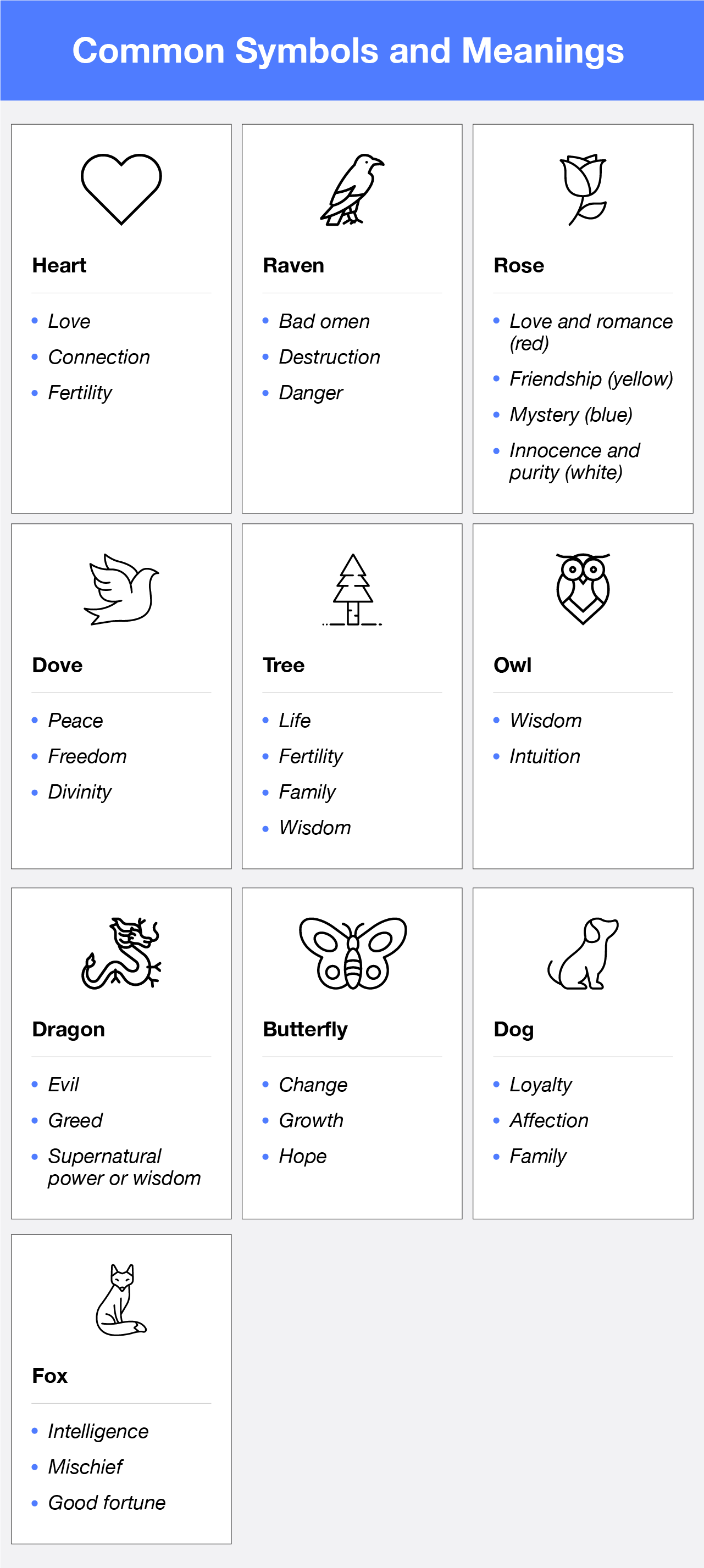

At their core, totem poles are not objects of worship. This is perhaps the most significant misconception to dispel. Unlike religious icons, they are not deified figures to which prayers are offered or sacrifices made. Instead, they serve as powerful visual narratives, mnemonic devices, and statements of identity. "Totem," derived from the Ojibwe word dodaem, refers to a family or clan symbol, often an animal or a natural phenomenon, which acts as a guardian or guide. On a pole, these totems come alive, layered one upon another, each figure contributing to a larger story.

The meanings embedded within these towering sculptures are multifaceted, reflecting the complex social and spiritual lives of the communities that create them.

1. Lineage and Genealogy: The Family Crests in Wood

Perhaps the most common function of totem poles is to proclaim and record the lineage and ancestral history of a family or clan. Much like European heraldry, specific animal figures – the Raven, Eagle, Bear, Wolf, Killer Whale, Beaver, Frog, and many more – serve as crests. These crests are not merely decorative; they represent the clan’s origin stories, its historical migration, important ancestors, or supernatural encounters that granted them power or status. A pole might display the crests of a family’s matriarchal and patriarchal lines, solidifying their claims to territory, resources, and social standing. "Each figure on a pole tells a part of our family’s journey," explains Robert Davidson, a renowned Haida artist. "It’s a visual record of who we are, where we come from, and our connection to the land and the supernatural world."

2. Storytelling and Oral Tradition: A Library in Cedar

Beyond genealogy, totem poles are magnificent storytellers. They can illustrate myths, legends, and historical events passed down through generations via oral tradition. A pole might depict a specific moment in a creation myth, the story of a culture hero, or a significant encounter between a human and a spirit being. The figures are arranged in a specific sequence, and while the pole itself doesn’t "read" like a book, it serves as a powerful visual aid for the storyteller, prompting memory and providing context during public recitations. For a community whose history and knowledge were traditionally conveyed through spoken word, these poles were crucial anchors, preserving narratives that defined their worldview and moral compass.

3. Status and Prestige: The Potlatch Connection

The creation and raising of a totem pole were inextricably linked to the Potlatch, a grand ceremonial feast central to Pacific Northwest Indigenous cultures. During a Potlatch, a host family would demonstrate their wealth and generosity by distributing gifts, feasting guests, and performing dances and songs. The raising of a new totem pole, often commissioned for a significant event like a marriage, the succession of a chief, or the commemoration of a deceased leader, was a highlight of the Potlatch. It publicly affirmed the family’s status, power, and prestige. The more elaborate the pole, the greater the expense and the higher the social standing of the commissioning family. The Potlatch, and by extension the totem pole, was a cornerstone of the socio-economic and political structure of these societies.

4. Memorial and Mortuary Poles: Honoring the Departed

Some totem poles served as memorials to the deceased or as mortuary poles. These poles were often hollowed out at the top to contain the remains (bones) of a high-ranking individual, or they might simply commemorate a chief or important elder, celebrating their life and achievements. The figures carved on such poles would often reflect the deceased’s crests, accomplishments, or significant life events, ensuring their legacy lived on in the collective memory of the community.

5. Welcome and House Poles: Guardians of the Threshold

Welcome poles, often featuring a prominent human-like figure with outstretched arms, were placed at the entrance to a village or a significant dwelling to greet visitors. They conveyed a message of hospitality and sometimes subtly warned outsiders of the community’s power. House poles, on the other hand, were integral structural components of longhouses, carved with crests or stories relevant to the family residing within, literally supporting the home and its inhabitants.

6. Shame Poles: A Rare but Potent Statement

While less common, shame poles (or ridicule poles) existed as a form of public shaming. If an individual or group failed to repay a debt or committed a significant offense against a community, a pole might be carved depicting the offending party in a humiliating manner. These poles served as a public and enduring reminder of the transgression, pressuring the individual or group to make amends. A famous example, though its interpretation is debated, is the "Chief Johnson Pole" in Ketchikan, Alaska, which some claim depicts a historical figure who failed to pay for a carving commission.

The Artistry and the Carver’s Vision

The creation of a totem pole is a monumental undertaking, demanding immense skill, patience, and a deep understanding of cultural narratives. Red and yellow cedar are the preferred woods due to their durability, workability, and resistance to rot. Carvers traditionally used adzes and chisels to meticulously shape the massive logs, transforming raw timber into expressive forms. Each figure, from the widest-eyed Raven to the most stoic Bear, is rendered with precise, stylized details, often adorned with traditional colors derived from natural pigments like charcoal (black), ochre (red/yellow), and copper oxides (blue/green).

The carver, a highly respected artist and knowledge keeper, does not merely sculpt; they interpret. They work closely with the commissioning family to ensure the pole accurately reflects their stories and lineage. It is a collaborative process, deeply embedded in community values, celebrating both individual artistry and collective identity.

Challenges, Resilience, and Revitalization

The arrival of European settlers brought profound disruption to Indigenous cultures. The Potlatch was banned by Canadian law from 1884 to 1951, directly impacting the ability of First Nations to create and raise new totem poles, as well as to pass on the associated traditions. Missionaries often condemned the poles as "pagan idols," leading to their destruction or removal to museums. Many ancient poles, left to the elements after villages were abandoned due to disease or forced relocation, eventually decayed.

Despite these devastating impacts, the tradition of totem pole carving has experienced a powerful resurgence in recent decades. A "cultural renaissance" has seen Indigenous artists reclaim their heritage, revitalizing carving schools, and educating the public about the true meanings of these magnificent artworks. Modern poles stand proudly in villages, cities, and museums, not just as historical artifacts but as living symbols of cultural pride, continuity, and sovereignty. Repatriation efforts are also underway, with communities working to bring ancestral poles back to their homelands from distant museums, reconnecting them with their rightful owners.

In conclusion, a totem pole is far more than a decorative monument. It is a sophisticated, multi-layered cultural document, a visual encyclopedia of a people’s past, present, and future. It speaks of ancestral connections, epic journeys, sacred stories, and the enduring power of community. To stand before a totem pole is to witness the profound artistry and deep spiritual wisdom of the Native American peoples of the Pacific Northwest – a silent, yet eloquent, reminder of a rich heritage that continues to stand tall against the test of time. Understanding their true meaning is a vital step in honoring and respecting the vibrant cultures that brought these magnificent sentinels of cedar to life.