Echoes in the Valley: Unearthing the Enduring Legacy of the Lenape in the Delaware Valley

Before the cobblestones of Philadelphia, the towering glass of Wilmington, or the suburban sprawl of Trenton, the Delaware Valley was a vibrant, living landscape, meticulously shaped and stewarded by its original inhabitants: the Lenape. Known to themselves as the “Lenni-Lenape,” or the “Original People,” their history in this fertile crescent, stretching from the lower Hudson River through modern-day New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, is a tapestry woven with threads of deep ecological knowledge, complex social structures, profound spiritual connection, and ultimately, a harrowing narrative of displacement and resilient survival. To understand the Delaware Valley is to understand the Lenape, whose enduring spirit continues to resonate through the land they once called home.

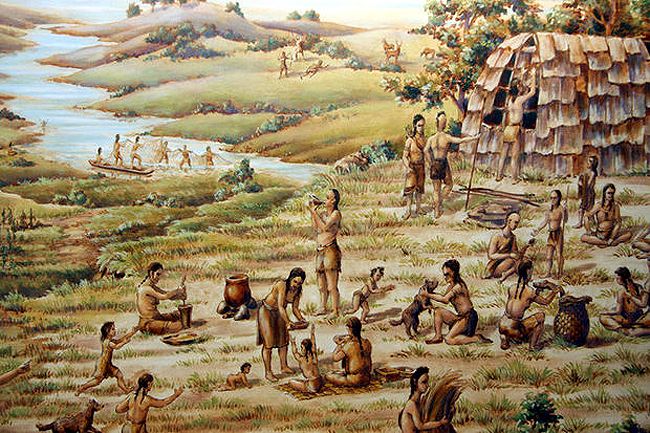

For over 10,000 years, long before European sails dotted the horizon, the Lenape thrived in a dynamic relationship with their environment. Their seasonal cycles mirrored the rhythms of nature. Spring brought the cultivation of corn, beans, and squash in fertile river bottomlands, while summer saw them fishing in the abundant waters of the Delaware River (which they knew as "Lenapewihittuck," the "Lenape River") and its tributaries. Autumn was a time for harvesting crops and hunting deer, elk, and bear in the vast forests, and winter saw them retreat to more sheltered encampments, relying on stored provisions and continued hunting.

Their society was sophisticated, organized into matrilineal clans—the Turtle, Turkey, and Wolf—which dictated lineage, social roles, and political alliances. Women held significant power, owning the land, controlling agricultural production, and often influencing decisions. Leadership was not based on inherited power but on wisdom, oratorical skill, and demonstrated ability to serve the community. Their spiritual beliefs were deeply intertwined with the land, viewing it not as a commodity to be owned, but as a sacred entity to be respected and cared for. Every plant, animal, and natural feature held spiritual significance, and their ceremonies and oral traditions reinforced this profound interconnectedness.

"The land was not something to be owned, but something to be cared for, a gift from the Creator," explains Nora Thompson Dean (Touching Leaves Woman), a respected Lenape elder and cultural preservationist, whose teachings offer invaluable insight into traditional Lenape worldview. "Our relationship with the earth was one of reciprocity, of giving and receiving." This philosophy of stewardship stood in stark contrast to the European concept of individual land ownership, a fundamental difference that would fuel centuries of misunderstanding and conflict.

The arrival of Europeans in the early 17th century marked a cataclysmic turning point. The Dutch were the first to establish a presence, followed by the Swedes and then the English. Initial interactions were often characterized by trade—Lenape furs for European metal tools, cloth, and trinkets. While these new goods offered convenience, they also introduced unforeseen dangers. European diseases, against which the Lenape had no immunity, swept through communities with devastating speed. Smallpox, measles, and influenza decimated populations, sometimes wiping out entire villages, profoundly weakening Lenape social structures and their ability to resist encroaching colonial powers. Estimates suggest that disease reduced the Lenape population by as much as 90% in some areas within a century of contact.

One of the most pivotal figures in the Lenape story is William Penn, who arrived in 1682 with a vision of a "Holy Experiment" based on peaceful coexistence and fair dealings with Native peoples. Penn famously sought to purchase land directly from the Lenape rather than simply seize it, famously signing treaties that he intended to be just. His respect for the Lenape was genuine, and for a time, Pennsylvania enjoyed a unique period of relative peace between settlers and Indigenous inhabitants, unlike many other colonies.

However, even Penn’s noble intentions were built upon a fundamental misunderstanding of land tenure. For the Lenape, selling land meant granting temporary use rights, perhaps for hunting or farming, but never absolute, perpetual ownership. For Europeans, a land deed meant permanent, exclusive possession. This cultural chasm, combined with increasing settler pressure and the insatiable demand for land, would inevitably lead to betrayal.

The most infamous example of this betrayal is the "Walking Purchase" of 1737. This fraudulent land deal, orchestrated by Penn’s sons and colonial authorities, effectively stripped the Lenape of their ancestral lands in southeastern Pennsylvania. The original, vaguely worded 1686 deed, which purportedly allowed the Penn family to claim land as far west as a man could walk in a day and a half, was reinterpreted and executed under deceitful circumstances. Instead of a leisurely stroll, the colonial agents hired three of the fastest runners in the colony, who cleared a path in advance, to cover as much ground as possible.

"The white people cheat us out of our land," lamented Lenape Chief Lapowinsa, according to historical accounts of the time. "They walk and walk and run, and we have no more land left." The runners covered an astonishing distance, over 64 miles, seizing approximately 1.2 million acres of prime Lenape territory – an area larger than Rhode Island – and pushing the Lenape out of their homelands between the Delaware and Lehigh Rivers. This event, a profound violation of trust and treaty, shattered the peace Penn had cultivated and forced thousands of Lenape to abandon their ancestral lands, seeking refuge further west.

The Walking Purchase was a watershed moment, accelerating the Lenape’s forced migration. Over the next century, caught between the escalating conflicts of European powers (such as the French and Indian War and the American Revolution) and the relentless westward expansion of American settlers, the Lenape were pushed from their homes repeatedly. They moved through Ohio, Indiana, Missouri, Kansas, and eventually, many were forcibly relocated to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) in the 1860s.

This diaspora scattered the Lenape across the continent, leading to the formation of distinct communities. Today, federally recognized Lenape tribes include the Delaware Nation and the Delaware Tribe of Indians in Oklahoma, and the Stockbridge-Munsee Community in Wisconsin. Other Lenape communities, such as the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation in New Jersey and the Lenape Indian Tribe of Delaware, continue to seek full federal recognition, fighting to reclaim their rightful place in the national narrative and secure the benefits of sovereignty.

Despite centuries of displacement, cultural suppression, and immense hardship, the Lenape spirit of resilience has endured. Modern Lenape communities are actively engaged in cultural revitalization efforts, striving to preserve their language (Munsee and Unami dialects), oral traditions, ceremonies, and historical memory. Language immersion programs, traditional arts workshops, and historical preservation initiatives are vital to reconnecting younger generations with their heritage.

"We are still here. Our ancestors walked this land, and their spirit is in this earth," states Chief Mark T. Gould, Sr. of the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation. "Our history is not just a past event; it is a living, breathing part of who we are today, and it guides our future."

The story of the Lenape in the Delaware Valley is more than a historical footnote; it is a foundational narrative that underpins the very landscape and identity of the region. It is a story of profound connection to the land, sophisticated cultural practices, and a devastating encounter with colonialism. But it is also a story of extraordinary resilience, of a people who, despite unimaginable losses, have maintained their identity, their traditions, and their unwavering connection to their ancestral homeland.

Understanding the Lenape past is crucial for understanding the present. Their history serves as a powerful reminder of the ongoing impacts of historical injustices and the importance of acknowledging the Indigenous peoples who walked this land first. By listening to the echoes in the valley, we can begin to truly see and honor the enduring legacy of the Lenni-Lenape, the Original People, whose spirit continues to shape the heart of the Delaware Valley.