Here is a 1200-word journalistic article in English about the Lakota Sioux reservations in South Dakota.

Echoes in the Badlands: The Enduring Spirit of Lakota Sioux Reservations

South Dakota’s vast prairies stretch out under an immense sky, a landscape of rolling grasslands, dramatic Badlands formations, and the distant, sacred Black Hills. Within this awe-inspiring expanse lie the Lakota Sioux reservations, lands that are both a testament to historical injustice and a vibrant stronghold of indigenous culture and resilience. These reservations – Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Cheyenne River, Standing Rock (partially in SD), Lower Brule, and Crow Creek – are often portrayed through statistics of poverty and struggle, but to truly understand them is to look beyond the numbers and recognize the profound strength, spiritual depth, and unwavering determination of the Lakota people, the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ, or Seven Council Fires.

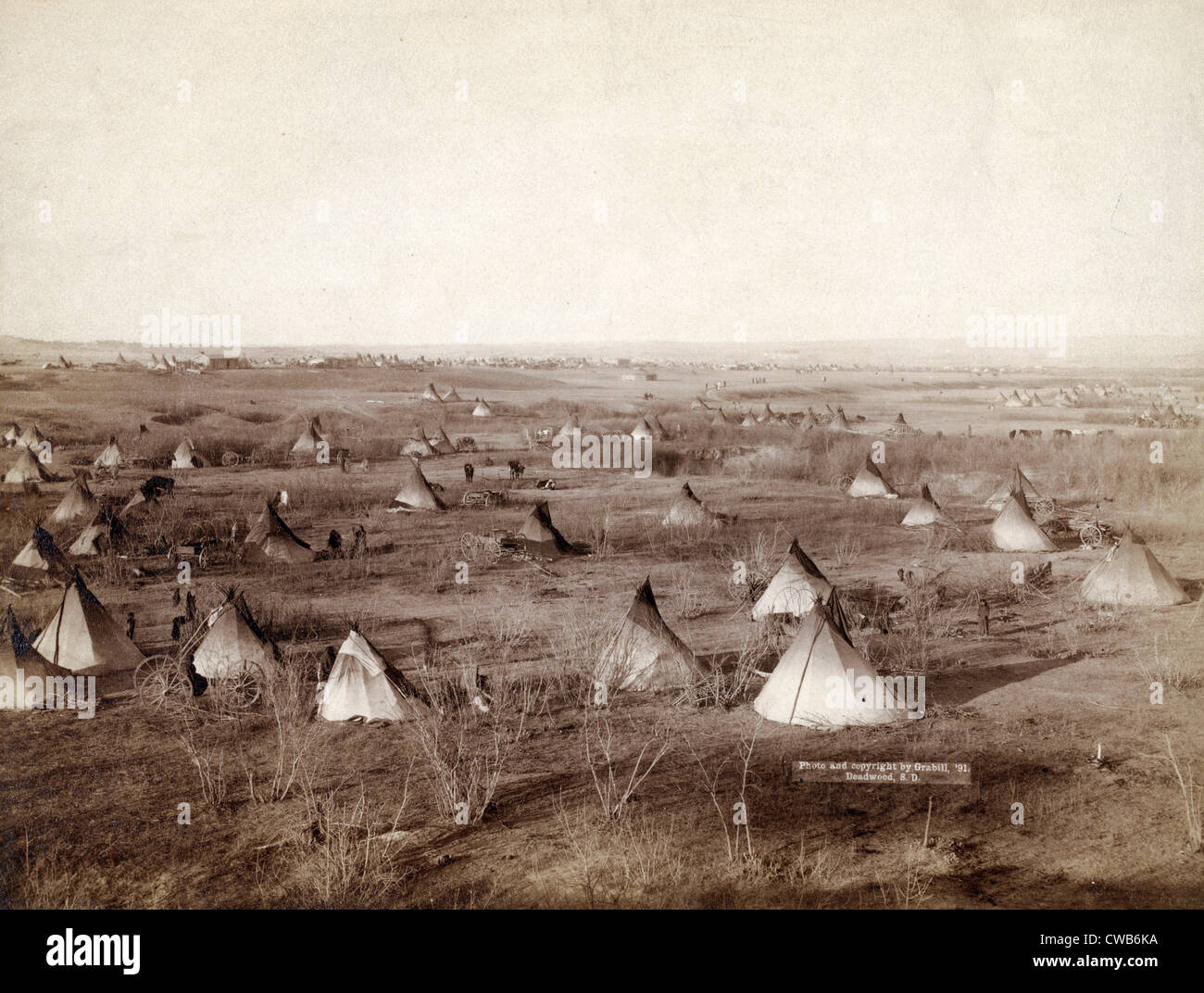

The story of the Lakota reservations is inextricably linked to the history of the American West. Before the arrival of European settlers, the Great Sioux Nation was a formidable power, its territory stretching across the northern plains. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, signed after years of conflict, guaranteed the Lakota a vast reservation, including the sacred Black Hills, "for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation of the Sioux Indians." However, this solemn promise was swiftly broken with the discovery of gold in the Black Hills in 1874. The ensuing gold rush led to a massive influx of settlers, escalating conflicts, and ultimately, the federal government’s seizure of the Black Hills and the breaking up of the Great Sioux Reservation into smaller, fragmented parcels.

The trauma continued with the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890, where hundreds of unarmed Lakota men, women, and children were slaughtered by the U.S. Army. This event, often seen as the symbolic end of the Indian Wars, left an indelible scar on the national conscience and on the collective memory of the Lakota people. Coupled with the forced assimilation policies of the boarding school era, which sought to "kill the Indian to save the man," stripping children of their language, culture, and identity, the foundations were laid for generations of intergenerational trauma, economic hardship, and systemic disadvantage.

Today, these historical wounds manifest in myriad ways across the reservations. Pine Ridge, home to the Oglala Lakota, is perhaps the most well-known and often cited as one of the poorest regions in the United States. Unemployment rates on Pine Ridge frequently hover between 80-90%, and per capita income can be as low as $8,000. Many residents live without electricity, running water, or adequate housing. The average life expectancy on Pine Ridge, particularly for men, is significantly lower than the national average, often cited in the late 40s or early 50s, comparable to some developing nations.

"Our people have faced a relentless assault on our way of life for centuries," says Cecelia Strong Heart, a community organizer on the Rosebud Reservation. "The poverty you see isn’t just a lack of money; it’s a direct consequence of stolen land, broken treaties, and systemic neglect. It’s a deprivation that touches every aspect of life – health, education, opportunity."

Healthcare on the reservations is provided primarily by the Indian Health Service (IHS), a federal agency chronically underfunded and understaffed. This results in limited access to specialists, long wait times, and inadequate facilities, exacerbating chronic health conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and substance abuse. The opioid crisis and high rates of alcoholism continue to devastate families and communities, often as a form of self-medication for the deep-seated trauma and despair. Mental health services are scarce, despite overwhelming need, particularly among youth facing high rates of suicide.

Education also faces immense challenges. Underfunded schools, a lack of resources, and the lingering effects of historical oppression contribute to lower graduation rates and limited pathways to higher education or skilled employment. "Our children deserve the best, but they often get the least," laments Michael Black Elk, a tribal council member from Cheyenne River. "We fight every day for better schools, for teachers who understand our culture, and for opportunities that keep our brightest minds here, building our communities."

Despite these daunting obstacles, the Lakota people exhibit an extraordinary resilience and a profound commitment to their cultural identity. Across the reservations, there is a powerful movement to revitalize the Lakota language, Lakȟótiya. Immersion schools and language programs are working tirelessly to teach the language to younger generations, recognizing it as the key to unlocking traditional knowledge, stories, and worldview. Elders, who are often the last fluent speakers, play a crucial role in these efforts, sharing their wisdom and preserving the ancestral tongue.

Spiritual practices and traditional ceremonies remain central to Lakota life. The Sun Dance, Sweat Lodge ceremonies, and Vision Quests are vital expressions of faith and community, connecting individuals to the sacred land and to their ancestors. Powwows, vibrant gatherings of song, dance, and regalia, are not merely cultural performances but powerful celebrations of identity, unity, and survival. They offer a space for healing, community bonding, and the transmission of cultural values to the youth.

"Our culture is our strength," states Elder Sarah Cloud, a respected knowledge keeper from Crow Creek. "It’s what has sustained us through the darkest times. The drum, the songs, the language – these are not just traditions; they are our lifeline, our connection to who we are as Lakota people. Mitákuye Oyásʼiŋ – All My Relations – reminds us that we are all interconnected, and our survival depends on that understanding."

Economic development on the reservations is a complex issue. While some tribes have found success with casinos, others struggle to attract investment due to remote locations, poor infrastructure, and regulatory hurdles. There is a growing focus on sustainable economic initiatives that align with Lakota values, such as renewable energy projects (wind and solar farms), buffalo ranching, traditional arts and crafts cooperatives, and culturally sensitive tourism. These efforts aim to create jobs and generate revenue while preserving the land and cultural heritage.

Advocacy for sovereignty and self-determination remains a core tenet. Tribal governments are working to assert their jurisdiction, manage their own resources, and develop their own solutions to community challenges. The ongoing demand for the return of the Black Hills, or at least just compensation for their illegal seizure, remains a powerful symbol of the unfulfilled promises and the pursuit of justice. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1980 that the Black Hills were illegally taken and offered $102 million in compensation, which the Lakota tribes have consistently refused, stating that the land was never for sale. The fund, now worth over $1 billion, remains untouched, a testament to their unwavering stance.

The youth are at the forefront of this enduring spirit. Programs focused on cultural education, leadership development, and addressing the impacts of historical trauma are empowering young Lakota individuals to become future leaders, fluent language speakers, and advocates for their people. They are embracing technology to share their stories, connect with global indigenous communities, and build bridges of understanding.

Visiting the Lakota reservations, whether it’s the rugged beauty of Pine Ridge, the vibrant community of Rosebud, or the expansive lands of Cheyenne River, is an experience that transcends the headlines. It’s an encounter with a people whose history is marked by profound loss, yet whose present is defined by an unyielding spirit of survival, cultural resurgence, and hope. Their struggle is a mirror reflecting the broader challenges of indigenous communities worldwide, but their resilience offers a powerful lesson in the enduring strength of identity, community, and the human spirit. The echoes in the Badlands are not just of past injustices, but of songs of defiance, prayers for healing, and the unwavering heartbeat of a people determined to thrive on their ancestral lands.