Echoes of the Longhouse: The Enduring Battle for Iroquois Sovereignty in New York

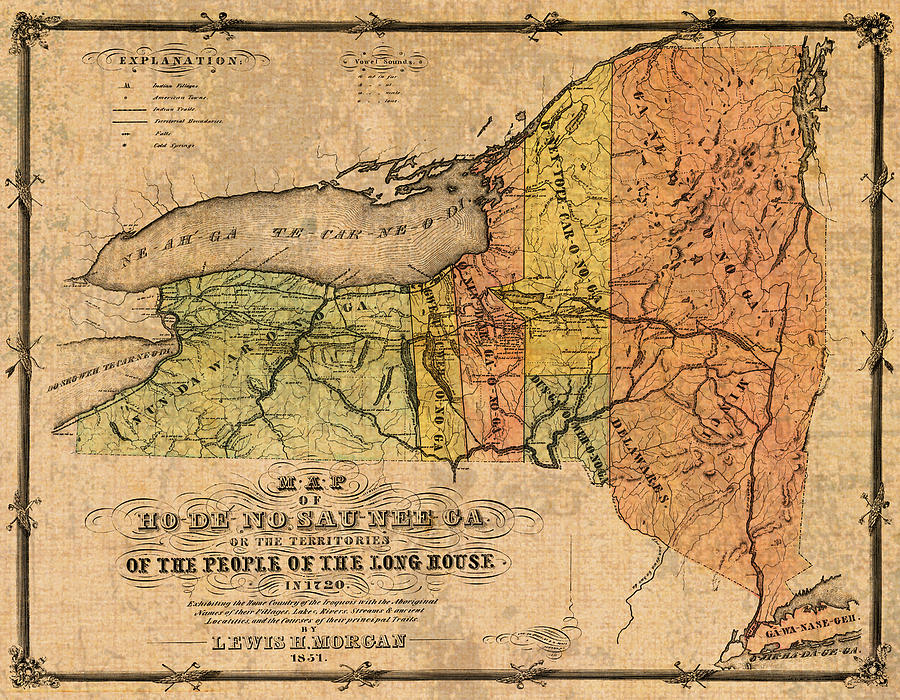

The rolling hills and fertile valleys of what is now New York State have, for centuries, been the ancestral home of the Haudenosaunee, or "People of the Longhouse." More commonly known as the Iroquois Confederacy, this formidable alliance of Six Nations – the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora – represents one of the oldest living participatory democracies in the world. Their enduring presence and persistent assertion of sovereignty within the borders of New York State are not relics of the past, but a vibrant, ongoing testament to self-determination, treaty rights, and cultural resilience.

To understand Iroquois sovereignty in New York is to delve into a complex tapestry woven from ancient traditions, colonial encounters, broken treaties, legal battles, and modern economic and cultural resurgence. It is a story of a distinct nation, or rather, a confederacy of nations, never fully conquered, continually navigating its relationship with a state and federal government that have, at various times, sought to diminish, assimilate, or simply ignore their inherent rights.

A Legacy Forged in Peace and Power: The Haudenosaunee Confederacy

Long before European contact, the Haudenosaunee established a sophisticated political and social system, codified in the Great Law of Peace (Gayanashagowa). This constitution, passed down orally through generations, united warring nations into a powerful league, fostering internal peace and presenting a formidable front to external adversaries. Its principles of shared governance, individual rights, and consensus-building have often been cited, albeit with academic debate, as an influence on the framers of the U.S. Constitution.

"Our ancestors established a system of governance that ensured peace and prosperity for generations," explains Oren Lyons, Faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation, in numerous public addresses. "The Great Law teaches us responsibility to the land, to the future generations, and to each other. This is the foundation of our sovereignty – not something granted, but something inherent."

The Haudenosaunee were sovereign nations, engaging in diplomacy, trade, and warfare with other indigenous peoples. When Europeans arrived, they were met not with disparate tribes, but with a powerful political entity. This was recognized in early treaties, most notably the Two Row Wampum (Guswenta) of 1613 with the Dutch. This symbolic belt, depicting two parallel rows of purple beads on a field of white, represented two vessels – a Haudenosaunee canoe and a European ship – traveling side-by-side down the river of life. Each vessel carried its own laws, customs, and people, with neither attempting to steer the other. This treaty established a fundamental principle of mutual respect and non-interference, a "nation-to-nation" relationship that remains central to Haudenosaunee claims today.

The Crucible of Colonialism and Revolution

The arrival of European powers – the Dutch, French, and then the British – brought new challenges and opportunities. The Haudenosaunee skillfully leveraged their strategic geographic position, playing European rivals against each other to maintain their autonomy. However, the American Revolution proved a devastating turning point. Divided in their allegiances, some nations sided with the British, others with the Americans. The brutal Sullivan-Clinton Expedition of 1779, ordered by George Washington, systematically destroyed Haudenosaunee villages and crops, effectively breaking the back of the Confederacy’s territorial power.

Following the war, the newly formed United States, despite earlier alliances and promises, began a systematic process of land acquisition and diminishment of Haudenosaunee sovereignty. Treaties signed under duress, often with individual nations rather than the full Confederacy, carved away vast tracts of land. New York State, eager for land to fuel its expansion, was particularly aggressive, often acting outside federal authority by negotiating directly with tribes, a practice later deemed illegal by the Supreme Court in cases like Oneida Nation v. County of Oneida.

Modern Manifestations of Sovereignty: From Land Claims to Casinos

The 20th century saw a shift from outright land seizure to attempts at assimilation and termination of tribal status. However, the tide began to turn in the latter half of the century with the rise of the self-determination movement. Today, Iroquois nations in New York assert their sovereignty through various means, often leading to friction with state and local governments.

1. Land Claims: The Oneida Nation v. County of Oneida cases (1974, 1985) were pivotal. The Supreme Court ruled that the Oneida Nation had a valid claim to lands illegally taken by New York State in the 18th and 19th centuries, affirming the validity of ancient treaties and the federal government’s trust responsibility. While these cases did not result in a return of all ancestral lands, they opened the door for other nations, like the Cayuga, to pursue their own claims, highlighting the enduring legal basis of treaty rights.

2. Taxation: One of the most persistent and visible areas of conflict is taxation. Iroquois nations, asserting their sovereign status, argue that their members and businesses on reservation lands are exempt from state sales, excise, and income taxes. This has led to contentious disputes over the sale of gasoline and cigarettes, often resulting in blockades, protests, and legal battles. For the nations, the ability to levy their own taxes and regulate commerce is a fundamental attribute of sovereignty, vital for funding essential services and economic development. New York State, however, views these exemptions as unfair competition and a loss of revenue.

3. Economic Development (Gaming): The rise of tribal gaming has been a game-changer for many Iroquois nations. Casinos like Seneca Niagara, Seneca Allegany, and Akwesasne Mohawk Casino Resort generate significant revenue, providing jobs, funding education, healthcare, and infrastructure, and allowing nations to escape the cycle of federal dependency. For example, the Seneca Nation of Indians has leveraged its gaming revenue to invest in diverse enterprises, build modern community facilities, and establish scholarships for its members. This economic self-sufficiency is a powerful expression of sovereignty, enabling nations to chart their own course.

4. Jurisdiction and Governance: Iroquois nations maintain their own police forces, courts, and social services on their territories. This parallel system of governance often creates complex jurisdictional issues with surrounding municipalities, particularly concerning law enforcement, environmental regulations, and infrastructure development. The Onondaga Nation, for instance, has been a vocal advocate for environmental protection, asserting its inherent responsibility as "Keepers of the Central Fire" to care for Onondaga Lake and its surrounding ecosystem, pushing for cleanup efforts against state and federal agencies.

5. Cultural Revitalization: Beyond legal and economic battles, sovereignty is deeply intertwined with cultural preservation. Efforts to revitalize the Haudenosaunee languages (Mohawk, Seneca, Onondaga, etc.), promote traditional ceremonies, and educate younger generations about their history and governance are acts of self-determination. These initiatives ensure that the unique identity and wisdom of the Haudenosaunee continue to thrive, providing a spiritual and philosophical anchor for their political struggles.

The Ongoing Struggle and the Path Forward

The relationship between Iroquois nations and New York State remains a dynamic and often tense one. While there have been instances of cooperation, particularly in areas like environmental protection and economic development, fundamental disagreements over the scope of tribal sovereignty persist. The state often views tribal lands as merely "Indian reservations" within its borders, subject to its ultimate authority, while the Haudenosaunee maintain they are distinct nations with inherent rights predating and superseding state law.

As a Haudenosaunee leader once articulated, "Sovereignty is not a gift. It is who we are. It is our responsibility to our ancestors, to our children, and to the Creator to maintain our way of life, our land, and our governance." This sentiment encapsulates the enduring spirit of the Iroquois.

The battle for Iroquois sovereignty in New York is not just a historical footnote; it is a living, breathing reality that shapes the political, economic, and cultural landscape of the state. It challenges conventional notions of state power, compels a re-evaluation of historical injustices, and offers a powerful model of indigenous self-determination. As New York continues to evolve, the voices from the Longhouse serve as a constant reminder that true justice and mutual respect require acknowledging and honoring the sovereign nations that have called this land home for millennia.