Enduring Homelands: A Deep Dive into the History of Iroquois Reservations in New York

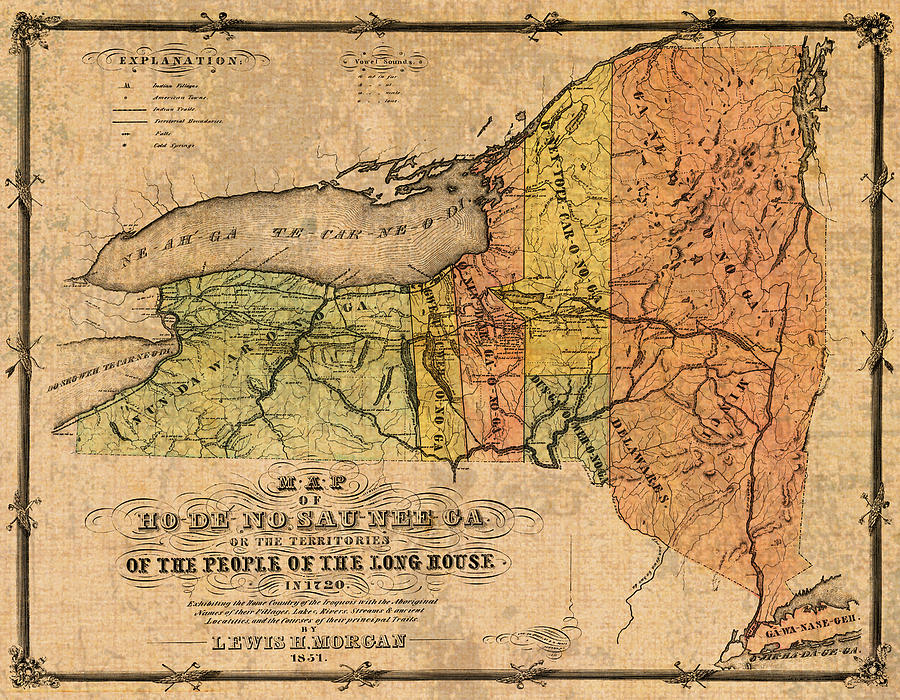

The verdant landscapes of New York State, from the Adirondack peaks to the Finger Lakes, whisper tales of ancient forests and powerful nations. Long before European settlers carved out their claims, this land was the ancestral domain of the Haudenosaunee, or "People of the Longhouse," known to outsiders as the Iroquois Confederacy. A sophisticated political and social entity comprising the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and later the Tuscarora nations, the Haudenosaunee wielded immense influence, shaping the destiny of a continent. Yet, their story in New York is also one of profound loss, relentless struggle, and astonishing resilience, largely encapsulated within the history of their reservations – parcels of land that, far from being gifts, represent the enduring remnants of a vast and vibrant empire.

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy, established centuries before European contact, was a beacon of democratic principles, its Great Law of Peace (Gayanashagowa) inspiring even some of the American Founding Fathers. Their traditional territory stretched across much of present-day New York, parts of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Canada. Their longhouses dotted the valleys, their agricultural fields sustained thriving communities, and their warriors defended their borders with fierce determination. This pre-colonial era was marked by a vibrant self-sufficiency and a deep spiritual connection to the land, where "ownership" was a foreign concept, replaced by stewardship and shared responsibility.

The arrival of European powers in the 17th century introduced a new, disruptive dynamic. The Haudenosaunee, strategically positioned between competing Dutch, French, and British interests, became crucial allies and formidable adversaries. They skillfully played these powers against each other, often leveraging their military strength and diplomatic acumen to maintain their sovereignty and expand their influence. The Covenant Chain, a series of alliances forged primarily with the British, solidified their political standing, demonstrating their capacity for complex international relations. However, this engagement also introduced new diseases, trade dependencies, and ultimately, the relentless pressure of colonial expansion.

The American Revolution proved to be a catastrophic turning point. The Confederacy, unable to maintain neutrality, found itself tragically divided. While the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Seneca largely sided with the British, the Oneida and Tuscarora supported the American colonists. This internal division, a direct consequence of external pressures, shattered the unity that had long been their strength. The war culminated in devastating campaigns like the Sullivan Expedition of 1779, where American forces under General John Sullivan systematically destroyed Haudenosaunee villages, crops, and orchards across central and western New York. This scorched-earth policy, ordered by George Washington, aimed to break the Confederacy’s power and ability to wage war, effectively starving them out. It was an act of immense brutality that forever altered the landscape and the lives of the Haudenosaunee.

With the American victory, the Haudenosaunee found themselves in a precarious position. Their British allies had abandoned them, and the victorious Americans viewed them as conquered enemies. The subsequent decades saw a relentless onslaught of land cessions, often under duress and through questionable means. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1784, intended to establish peace and boundaries, saw significant land cessions by the Haudenosaunee to the United States. This was followed by the critically important Treaty of Canandaigua in 1794, also known as the Pickering Treaty, which re-established peace, recognized the sovereignty of the Six Nations, and affirmed their right to occupy their remaining reserved lands "to have and to hold to them and their posterity forever." This treaty, signed by President George Washington, remains a foundational document governing the relationship between the Haudenosaunee and the United States, yet its promises would be continually challenged.

Crucially, New York State played an exceptionally aggressive role in dispossessing the Haudenosaunee. Unlike other states, New York often circumvented federal authority, directly negotiating with individual Haudenosaunee nations or even factions within them, despite the 1790 Nonintercourse Act which required federal approval for land transactions with Native American tribes. These state-sanctioned purchases, often driven by land speculators and settler demands, chipped away at the Haudenosaunee’s remaining territory at an alarming rate. "The Great Sale" of 1788-1790, orchestrated by New York, saw millions of acres transferred from the Haudenosaunee, reducing their ancestral lands to a patchwork of scattered reservations. These reservations – such as Allegany, Cattaraugus, Tuscarora, Onondaga, St. Regis Mohawk, and Oneida – were not "given" to them, but were lands "reserved" by the nations from their original, much larger holdings. They were the last fragments of their patrimony, held onto with fierce determination.

The 19th century brought further challenges. Confined to diminishing territories, the Haudenosaunee faced immense pressure to assimilate. Missionaries arrived, promoting Christianity and Western education, often undermining traditional spiritual beliefs and social structures. Yet, this era also witnessed a powerful cultural revitalization movement through the teachings of Handsome Lake (Sganyodaiyo), a Seneca prophet. His Code of Handsome Lake (Gaiwiio), preached in the early 1800s, called for a return to traditional values, moral reform, and a selective adoption of certain aspects of Euro-American culture while rejecting others. This Longhouse Religion provided spiritual guidance and cultural resilience in the face of immense adversity, helping to preserve a distinct Haudenosaunee identity.

The 20th century saw the Haudenosaunee navigate a complex web of federal Indian policies. The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, which sought to promote tribal self-governance, was met with mixed reactions. While some nations adopted IRA constitutions, others, particularly the more traditional Haudenosaunee communities, rejected it, viewing it as another attempt by the federal government to impose foreign governance structures and undermine their traditional systems rooted in the Great Law of Peace. Later, the Termination Era of the 1950s and 60s, which aimed to end federal recognition and services to tribes, was vigorously resisted by the Haudenosaunee, who successfully fought to maintain their sovereign status and treaty rights.

Today, the Haudenosaunee nations in New York continue to assert their sovereignty and cultural distinctiveness. Their reservations, though geographically small compared to their ancestral domain, are vibrant centers of cultural preservation, political activism, and economic development. The Oneida Nation, for instance, has achieved significant economic success through gaming enterprises, which has allowed them to invest in education, healthcare, and infrastructure for their community. However, this economic development often brings its own set of challenges, including jurisdictional disputes with New York State over taxation and law enforcement, highlighting the ongoing tension between tribal sovereignty and state authority.

Land claims, rooted in the historical injustices of illegal land cessions, remain a significant aspect of contemporary Haudenosaunee struggles. The Oneida Nation’s long-standing land claim, culminating in the Supreme Court case Oneida Nation v. County of Oneida (1974), affirmed their aboriginal title and the right to pursue claims based on violations of the Nonintercourse Act. While a complete return of ancestral lands is often impractical, these claims seek justice, recognition, and compensation for historical wrongs.

The Haudenosaunee reservations in New York are not mere historical relics; they are living, breathing communities where the Great Law of Peace continues to guide, language immersion programs revive ancient tongues, and traditional ceremonies connect generations to their heritage. From the Mohawk ironworkers who built New York City’s skyscrapers to the contemporary artists and scholars preserving their culture, the Haudenosaunee people demonstrate an unwavering commitment to their identity. Their history in New York is a powerful testament to the enduring spirit of a people who, despite centuries of land loss, political pressure, and cultural assault, continue to thrive, demanding recognition of their inherent sovereignty and asserting their rightful place as the original stewards of this land. Their story is an essential, often overlooked, chapter in the narrative of New York and indeed, of America itself.