Influential Native American Tribal Leaders: Historical Figures and Modern Chiefs

The tapestry of American history is rich with narratives of resilience, leadership, and the enduring spirit of its Indigenous peoples. From the earliest encounters with European settlers to the complex challenges of the 21st century, Native American tribal leaders have stood as vanguards of their communities, protectors of their lands, and fierce advocates for their sovereignty and cultural survival. Their stories are not merely footnotes in history; they are foundational pillars of a nation often reluctant to acknowledge their profound impact. This article delves into the lives and legacies of influential Native American leaders, examining both the iconic figures of the past whose names resonate with defiance and wisdom, and the contemporary chiefs and presidents who navigate the intricate landscape of modern tribal governance, economic development, and cultural revitalization.

Echoes of Resistance and Sovereignty: Historical Titans

The historical record is replete with Native American leaders who, facing existential threats, rallied their people, forged alliances, and fought with unparalleled courage to preserve their way of life. These figures often operated in an era of relentless territorial encroachment, forced assimilation policies, and broken treaties, yet their leadership shone as beacons of defiance and self-determination.

One of the earliest and most formidable figures was Pontiac (Obwandiyag), an Odawa war chief who spearheaded a pan-tribal confederacy in 1763 against British expansion into the Great Lakes region following the French and Indian War. Pontiac’s War, a sophisticated and coordinated uprising, demonstrated a powerful, unified Indigenous response to colonial aggression. Though ultimately unsuccessful in permanently expelling the British, Pontiac’s actions forced the British Crown to issue the Proclamation of 1763, which, at least on paper, restricted colonial settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains, acknowledging Indigenous land rights, however temporarily.

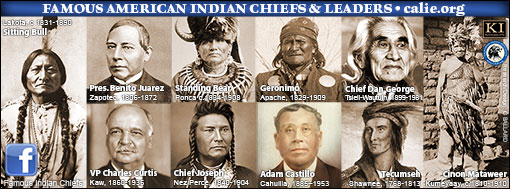

Decades later, Tecumseh, a Shawnee warrior and orator, emerged as a brilliant strategist and diplomat. In the early 19th century, he envisioned and tirelessly worked to establish a vast Native American confederacy to resist U.S. expansion. Alongside his brother, Tenskwatawa (The Prophet), Tecumseh preached a message of cultural revitalization and political unity, urging tribes to reject assimilation and stand together against the encroaching tide. His efforts culminated in significant military clashes, most notably the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811 and his alliance with the British during the War of 1812. Tecumseh’s death in the Battle of the Thames in 1813 dealt a severe blow to the confederacy, but his vision of a united Indigenous front remains an enduring symbol of resistance. "A single twig breaks, but a bundle of twigs is strong," he famously said, encapsulating his philosophy of unity.

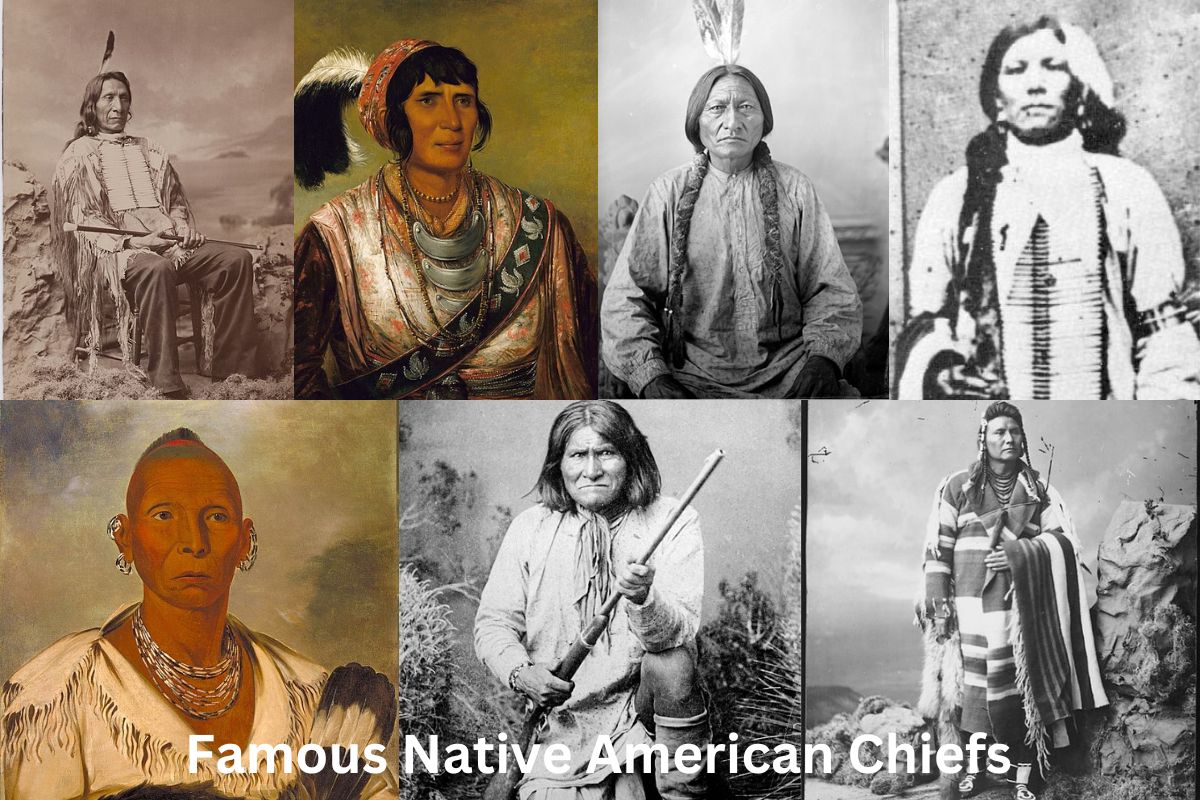

The Plains Wars of the mid-19th century brought forth legendary figures like Crazy Horse (Tȟašúŋke Witkó) and Sitting Bull (Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake) of the Lakota. Crazy Horse, an Oglala Lakota war leader, was renowned for his ferocity in battle and his elusive nature. He played a pivotal role in key victories against the U.S. Army, including the Fetterman Fight (1866) and the Battle of Little Bighorn (1876), where General Custer’s forces were annihilated. Crazy Horse embodied the Lakota warrior spirit, fighting relentlessly to protect his people’s sacred lands and traditional way of life until his tragic death in 1877 while resisting imprisonment. He never signed a treaty with the U.S. government, steadfastly refusing to relinquish his people’s freedom.

Sitting Bull, a Hunkpapa Lakota holy man and chief, was Crazy Horse’s elder and spiritual mentor. His prophetic vision before Little Bighorn, foretelling a great victory over the soldiers, galvanized the Lakota and Cheyenne warriors. Beyond his military prowess, Sitting Bull was a profound spiritual leader who upheld traditional Lakota values. His unwavering resistance to U.S. policies led him to Canada for several years before ultimately surrendering due to starvation. Even in later years, while performing with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, he used his platform to highlight the plight of his people. He was tragically killed in 1890 during an attempt to arrest him, an event that contributed to the atmosphere of fear leading up to the Wounded Knee Massacre.

In the American Southwest, Geronimo (Goyaałé), a Chiricahua Apache leader, became a symbol of fierce, unyielding defiance. For decades, he led small bands of Apache warriors in daring raids and evasions against both U.S. and Mexican forces, making him the last Native American war chief to formally surrender to the U.S. government in 1886. Geronimo’s extraordinary ability to evade capture, often operating with minimal resources in harsh desert terrain, made him a legendary figure, feared by his enemies and revered by his people for his indomitable will to resist encroachment on Apache lands and traditional lifeways.

Finally, Chief Joseph (Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it) of the Nez Perce is remembered for his brilliant strategic retreat and his eloquent plea for peace. In 1877, facing forced removal from their ancestral lands in Oregon, Chief Joseph led his people on an epic 1,170-mile flight towards Canada, outmaneuvering and fighting numerous U.S. Army units. His tactical brilliance and humanitarian concern for his people earned him widespread respect. His surrender speech, "From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever," remains one of the most poignant expressions of sorrow and resignation in American history, yet it also speaks to a profound love for his people and a desperate hope for their survival.

Architects of Survival and Self-Governance: Adaptability and Vision

While many leaders are celebrated for their resistance on the battlefield, others played equally crucial roles in navigating the treacherous waters of assimilation through diplomacy, legal challenges, and cultural preservation.

John Ross (Guwisguwi), Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation for nearly 40 years, stands as a paramount example. A mixed-blood leader who spoke English, Ross skillfully utilized the American legal system and diplomacy to protect Cherokee sovereignty. He fought tirelessly against forced removal, famously taking the Cherokee Nation’s case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), where the Court sided with the Cherokee. Despite this legal victory, President Andrew Jackson defied the ruling, leading to the infamous Trail of Tears. Ross’s leadership during this horrific period, and his subsequent efforts to rebuild the Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory, underscore his unwavering commitment to his people’s survival and self-governance.

Another pivotal figure in the fight for human rights was Standing Bear of the Ponca tribe. In 1879, after the forced removal of his people from Nebraska to Indian Territory, Standing Bear sought to return the body of his deceased son to their ancestral lands for burial. Arrested for leaving the reservation, he became the plaintiff in Standing Bear v. Crook, a landmark federal court case. His powerful testimony, "I am a man. The same God made us both," moved the court to declare that "an Indian is a person within the meaning of the law," granting Native Americans the right of habeas corpus and establishing their right to sue and be sued, laying critical groundwork for future civil rights.

Modern Chiefs: Navigating the 21st Century

The challenges faced by contemporary Native American leaders are different in nature but no less significant. Today’s chiefs, governors, and presidents are at the forefront of a movement for self-determination, economic development, cultural revitalization, and environmental protection, often operating within complex federal and state legal frameworks.

One of the most inspiring modern leaders was Wilma Mankiller, who in 1985 became the first female Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, one of the largest tribes in the United States. Mankiller’s tenure, which lasted for a decade, was marked by an emphasis on community development, self-help initiatives, and addressing critical issues such as healthcare, education, and housing. She famously spearheaded projects like the Bell Water Project, where community members worked together to lay water lines, fostering a sense of collective empowerment. Her leadership transformed the Cherokee Nation, demonstrating that Indigenous governance could be both effective and deeply rooted in community values. "The most important thing is to believe in yourself and to believe in your people," she often said.

Peterson Zah, the first president of the Navajo Nation (serving from 1990 to 1995), played a crucial role in transitioning the Navajo government from a tribal council system to a more modern, tripartite presidential system. Zah focused on strengthening the Navajo Nation’s sovereignty, improving education, and diversifying its economy beyond reliance on natural resources. His work laid the groundwork for greater self-governance and economic stability for the largest Native American tribe by land area.

In the realm of national advocacy, leaders like W. Ron Allen, Chairman of the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe in Washington State, have been instrumental. Serving for decades, Allen has been a powerful voice for tribal sovereignty, economic development (including tribal gaming), and environmental protection on both local and national stages, including as president of the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI). His work underscores the critical role modern tribal leaders play in shaping federal policy and protecting treaty rights.

More recently, figures like Fawn Sharp, former President of the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) and President of the Quinault Indian Nation, exemplify the contemporary fight for environmental justice and resource protection. Sharp is a staunch advocate for tribal treaty rights, particularly concerning fishing and natural resource management, and has been a vocal leader on climate change impacts on Indigenous communities. Her leadership highlights the intersection of tribal sovereignty, environmental stewardship, and global challenges.

Similarly, Chuck Hoskin Jr., the current Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, continues the legacy of leaders like Wilma Mankiller and John Ross. His administration focuses on strengthening the Cherokee language, addressing the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW), expanding healthcare access, and advocating for the tribe’s interests in Washington D.C. His efforts reflect the ongoing commitment of modern leaders to cultural preservation and the well-being of their citizens.

An Enduring Legacy of Resilience

From Pontiac’s unified resistance to Wilma Mankiller’s community-driven development, and from Tecumseh’s vision of a united Indigenous front to Fawn Sharp’s advocacy for environmental justice, the thread of resolute leadership runs unbroken through Native American history. These leaders, whether facing overwhelming military might or navigating complex legal and political systems, share common attributes: an unwavering dedication to their people, a profound respect for their cultural heritage, and an unyielding commitment to sovereignty.

Their stories are not just historical accounts; they are living testaments to the enduring strength and adaptability of Native American nations. They remind us that Indigenous leadership is not a relic of the past but a dynamic, evolving force that continues to shape the future of tribal communities and contributes significantly to the broader narrative of justice, resilience, and self-determination in America and beyond. The voices of these influential leaders, past and present, echo with wisdom, courage, and the timeless call for respect and recognition.