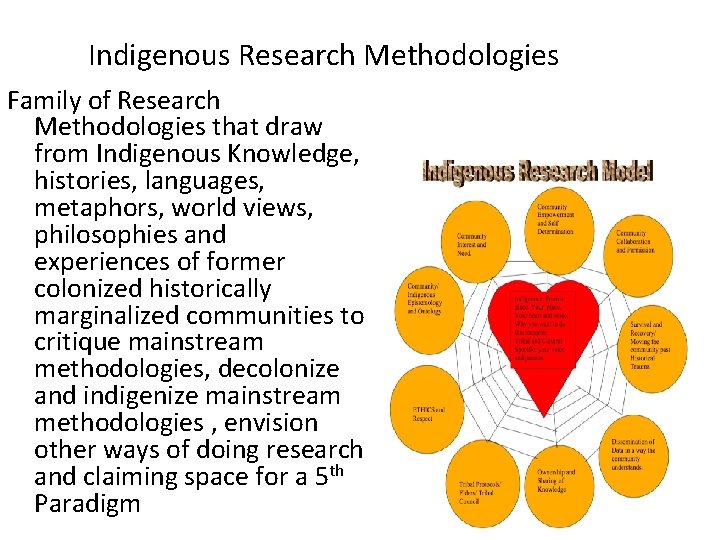

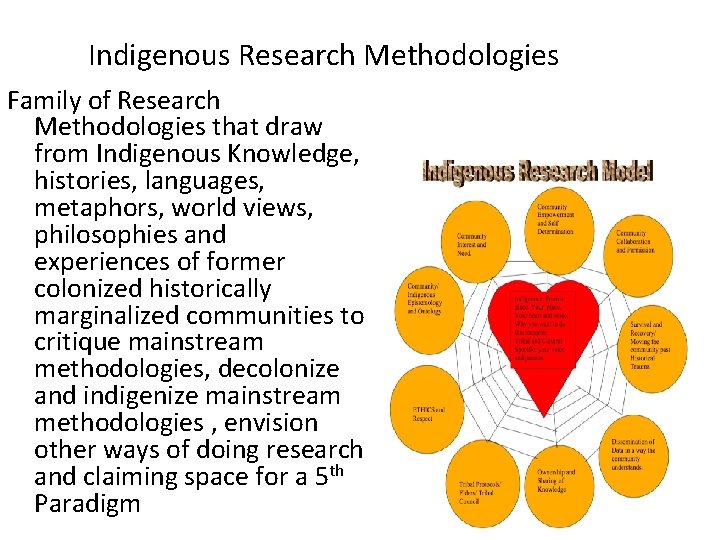

Beyond Extraction: The Transformative Power of Indigenous Research Methodologies

For centuries, the academic world, largely shaped by Western paradigms, has often viewed Indigenous communities through a lens of exoticism, deficit, or as mere subjects for study. Research, a noble pursuit in theory, has frequently been a tool of extraction, stripping Indigenous knowledge, stories, and resources without adequate reciprocity or benefit. As Māori scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith famously articulated in her seminal work, Decolonizing Methodologies, for many Indigenous peoples, "research is probably one of the dirtiest words in the Indigenous world’s vocabulary."

This legacy of harm, rooted in colonial practices and epistemologies, has necessitated a radical shift in how knowledge is sought, created, and disseminated within and about Indigenous communities. Enter Indigenous Research Methodologies (IRMs) – a vibrant, evolving, and profoundly transformative approach that champions self-determination, ethical engagement, and the centering of Indigenous worldviews, knowledge systems, and protocols. Far from being a niche sub-field, IRMs represent a decolonizing force, challenging the very foundations of Western academia and paving the way for more just, respectful, and relevant knowledge production for all.

The Harmful Legacy: Why IRMs Were Born

To understand the imperative behind IRMs, one must first confront the historical backdrop against which they emerged. Traditional Western research, often characterized by its pursuit of "objective" truth, has historically positioned the researcher as an external, neutral expert and Indigenous communities as passive data sources. This approach led to:

- Extraction without Reciprocity: Researchers would collect vast amounts of data – stories, cultural practices, traditional ecological knowledge – only to publish findings in academic journals inaccessible to the communities themselves. The knowledge was taken, but little, if anything, was given back.

- Misrepresentation and Stereotyping: Findings were frequently filtered through a colonial lens, leading to the perpetuation of harmful stereotypes, the exoticization of cultural practices, or the framing of Indigenous communities as "problems" needing Western intervention.

- Disregard for Indigenous Epistemologies: Western research often dismissed Indigenous ways of knowing – oral traditions, spiritual connections to land, ceremonial practices – as unscientific or anecdotal, thus devaluing millennia of accumulated wisdom.

- Lack of Informed Consent and Ownership: Research was often conducted without meaningful consent, and communities rarely retained ownership or control over their own data and narratives. The notorious example of the Havasupai Tribe’s genetic samples being used for unauthorized research underscores this profound breach of trust and ethics.

This history created a deep distrust of research and researchers within Indigenous communities, making it clear that a new paradigm was desperately needed – one that prioritized Indigenous voices, values, and visions.

Core Principles: Reclaiming Research as Relationship

At the heart of Indigenous Research Methodologies lies a profound philosophical departure from Western norms. Instead of viewing research as a detached, objective pursuit, IRMs frame it as a relational, reciprocal, and responsible endeavor. Key principles include:

- Relationality: Indigenous worldviews emphasize the interconnectedness of all things – humans, land, animals, plants, spirits, ancestors, and future generations. As Indigenous scholar Shawn Wilson writes in Research Is Ceremony, "Research is a ceremony, a process of relationship and accountability to these relationships." This means research is not just about human subjects but about the entire web of life and the responsibilities inherent within it.

- Reciprocity: The "give and take" is fundamental. Research must benefit the community being studied, not just the researcher or academic institution. This can manifest as capacity building, direct service, returning knowledge in accessible formats, or supporting community-led initiatives.

- Respect: This principle dictates adherence to cultural protocols, respect for Elders and knowledge keepers, and recognition of the sacredness of certain knowledge. It involves humility on the part of the researcher and a genuine willingness to learn and be guided by community wisdom.

- Responsibility: Researchers are accountable to the community, not just to their academic supervisors or funders. This includes ensuring the research is conducted ethically, that findings are accurate and respectful, and that the process contributes positively to community well-being.

- Relevance: Research questions must arise from the needs and priorities of Indigenous communities themselves, rather than being imposed externally. This ensures the research directly addresses issues of importance to the people it purports to serve.

- Rigor: While often defined differently than in Western academia, rigor in IRMs is paramount. It involves cultural appropriateness, ethical integrity, community validation, and the depth of understanding derived from Indigenous epistemologies.

These principles coalesce into a framework that often prioritizes self-determination and sovereignty over knowledge. A critical concept emerging from First Nations in Canada is OCAP® (Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession), which asserts that First Nations communities must control their own data. This means they own the information, control how it’s collected, used, and disclosed, have access to it, and physically possess it. Similar principles are articulated as OAC (Ownership, Access, Control) in Australia and Aotearoa (New Zealand), reflecting a global Indigenous movement to reclaim data governance.

Diverse Methodologies: Weaving Indigenous Ways of Knowing

Indigenous Research Methodologies are not a monolithic approach but rather a tapestry woven from diverse cultural practices, traditions, and epistemologies. They often blend seamlessly with, or adapt, elements of Western methodologies while firmly grounding them in Indigenous worldviews. Some common approaches include:

- Storytelling and Oral Histories: Indigenous cultures are rich in oral traditions. Storytelling is not just entertainment but a profound method of transmitting knowledge, values, and history. As a research methodology, it respects the narrative as a valid form of data and knowledge, often yielding insights that quantitative data cannot capture. It prioritizes voice and lived experience.

- Ceremony and Land-Based Learning: For many Indigenous peoples, knowledge is intrinsically linked to land and spiritual practices. Research might incorporate ceremony, land-based camps, or traditional teachings as central components of data collection and analysis, recognizing that knowledge is embodied and situated. This approach emphasizes holistic understanding and the interconnectedness of all life.

- Participatory Action Research (PAR) and Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR): While not exclusively Indigenous, these approaches align perfectly with IRM principles. They emphasize collaboration at every stage of the research process, from question formulation to dissemination. Community members are co-researchers, ensuring that the research is relevant, empowering, and directly addresses community needs.

- Visual and Performative Arts: Art, music, dance, and theatre can be powerful mediums for expressing knowledge and understanding, especially for those for whom written language is not primary or who prefer non-linear forms of communication. These methods offer alternative ways to collect, analyze, and disseminate findings, engaging broader community participation.

- Elder and Knowledge Keeper Guidance: Elders are living libraries of cultural wisdom, history, and spiritual understanding. Their guidance is paramount in IRMs, shaping research questions, validating findings, and ensuring cultural protocols are respected. They are not merely "informants" but central figures in the knowledge creation process.

Impact and Transformation: Healing and Empowerment

The adoption and growth of Indigenous Research Methodologies have had a profound and positive impact:

- Empowerment and Self-Determination: IRMs shift power dynamics, moving Indigenous communities from being subjects of research to owners and drivers of their own knowledge agendas. This fosters a sense of agency and strengthens self-determination.

- Healing and Reconciliation: By creating safe spaces for stories to be told and validated, IRMs can contribute to individual and collective healing from historical trauma. They foster reconciliation by promoting understanding and respect between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

- Authentic Representation: Research conducted through an Indigenous lens produces more accurate, nuanced, and respectful representations of Indigenous cultures, histories, and contemporary realities, challenging colonial narratives and stereotypes.

- Relevant Policy and Practice: By addressing community-identified needs, IRMs generate knowledge that is directly applicable to policy development, program design, and social interventions, leading to more effective and culturally appropriate outcomes.

- Cultural Revitalization: Engaging with traditional knowledge systems and practices through research can contribute to the revitalization and intergenerational transmission of language, culture, and identity. As scholar Eve Tuck advocates, IRMs shift from "damage-centered" research to "desire-based" research, focusing on Indigenous strengths, aspirations, and sovereignty rather than solely on their struggles.

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite their transformative potential, IRMs face challenges. Institutional resistance, deeply entrenched Western academic norms, funding structures that favor conventional approaches, and a lack of understanding among non-Indigenous researchers can impede their full adoption. The danger of "tokenism" – superficial inclusion without genuine power-sharing – also looms.

The path forward requires ongoing education, sustained advocacy, and a commitment to genuine partnership. Non-Indigenous researchers and institutions must critically examine their own biases, actively decolonize their practices, and commit to capacity building within Indigenous communities. It means recognizing Indigenous knowledge as legitimate and rigorous, not merely as "cultural context" for Western theories.

Conclusion

Indigenous Research Methodologies are more than just a set of techniques; they represent a paradigm shift – a radical reimagining of what research can be. They are about justice, respect, and the fundamental right of Indigenous peoples to define themselves, control their own narratives, and shape their own futures through their own ways of knowing. By embracing relationality, reciprocity, respect, and responsibility, IRMs offer a powerful antidote to the colonial legacy of extraction. They invite all researchers to engage in a more ethical, holistic, and ultimately, more human way of seeking knowledge, benefiting not only Indigenous communities but enriching the entire academic landscape with diverse epistemologies and a deeper understanding of our interconnected world.