The Unfinished Promise: The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 and the Paradox of Belonging

On June 2, 1924, a seemingly straightforward act of Congress, the Indian Citizenship Act (also known as the Snyder Act), declared that "all noncitizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States be, and they are hereby, declared to be citizens of the United States." On its surface, this legislation appeared to rectify a century-old anomaly, extending the full rights of citizenship to the continent’s original inhabitants. Yet, the story of the 1924 Act is far from simple; it is a complex tapestry woven with threads of assimilation, patriotism, legal limbo, and the enduring struggle for self-determination that continues to resonate today. To understand its profound significance, one must delve into the fraught historical context that preceded it, a period marked by shifting federal policies, broken promises, and the relentless pressure to "civilize" Native peoples.

For centuries after European contact, Indigenous nations existed as sovereign entities, recognized through treaties as distinct political bodies. However, as the United States expanded westward, this recognition gradually eroded. The landmark Supreme Court cases of Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832), while affirming tribal sovereignty against state encroachment, ultimately classified Native tribes as "domestic dependent nations"—a legal oxymoron that placed them under the paternalistic "guardianship" of the federal government. This status denied them the rights of full citizenship, treating them instead as wards of the state, subject to federal control over their lands, resources, and even their daily lives.

The 19th century witnessed a brutal and relentless campaign of forced removal and cultural destruction. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 led to the Trail of Tears, forcibly relocating thousands of Native people from their ancestral lands. Following the Civil War, the federal government pivoted from removal to a policy of "assimilation," a euphemism for cultural genocide. The underlying belief was that Native Americans could only survive if they shed their Indigenous identities and adopted white American customs, language, religion, and economic practices.

Central to this assimilationist agenda was the Dawes General Allotment Act of 1887. This legislation aimed to dismantle tribal communal landholdings by dividing reservations into individual parcels of land, allotted to individual Native families. The surplus land was then sold off to non-Native settlers, further diminishing tribal territories. The architects of the Dawes Act believed that private property ownership would instill individualism and a capitalist work ethic, transforming Native Americans into self-sufficient farmers. Those who accepted allotments and adopted "civilized" ways were often granted citizenship, a piecemeal and conditional approach that bypassed the majority. "The object of this bill is to get rid of the Indian problem," stated Senator Henry L. Dawes, "to break up the tribal mass, and to set up the Indian as a man." The devastating reality was that the Dawes Act led to the loss of two-thirds of the remaining Native American land base and profoundly disrupted tribal social structures, but largely failed to integrate Native peoples into the mainstream.

Parallel to land allotment were the notorious Indian boarding schools. Institutions like the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, founded by Richard Henry Pratt, operated under the chilling philosophy: "Kill the Indian, save the man." Native children were forcibly removed from their families, forbidden to speak their languages, practice their spiritual traditions, or wear their traditional clothing. Their hair was cut, their names changed, and they were subjected to harsh discipline and manual labor, all in the name of "civilization." While some individuals who graduated from these schools did achieve a measure of success in the dominant society, the immense psychological and cultural trauma inflicted upon generations of Native children left an indelible scar.

Despite these aggressive assimilation efforts, the legal status of most Native Americans remained ambiguous. They were born on American soil, yet were not considered citizens. They lived under federal jurisdiction, yet lacked the fundamental rights afforded to other residents. This peculiar status persisted into the early 20th century, setting the stage for a critical turning point: World War I.

When the United States entered the Great War in 1917, thousands of Native Americans, despite their non-citizen status, eagerly volunteered for military service. Estimates suggest that over 12,000 Native Americans, approximately 25% of the male Native population of fighting age, served in the armed forces. They served with distinction and bravery, often in combat roles, earning numerous commendations. The famed Choctaw Code Talkers, for example, used their native language to transmit unbreakable messages, contributing significantly to Allied victories.

The irony of this situation was not lost on the American public or on Native communities themselves. These men, who were deemed fit to fight and die for a nation, were simultaneously denied the right to vote, own land freely, or even leave their reservations without permission. "It is an unanswerable question," argued Representative Homer P. Snyder, the bill’s sponsor, "why these men, who were fighting side by side with their white brothers, should be denied the rights and privileges of citizenship."

The valor of Native American soldiers, coupled with a growing sense of national introspection after the war, created an undeniable moral imperative for change. Progressive reformers, Native American advocacy groups like the Society of American Indians (SAI), and even some government officials began to champion the cause of universal Native American citizenship. Charles Curtis, a Kaw Nation member who would later become Vice President under Herbert Hoover, was a prominent voice advocating for the rights of his people.

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, introduced by Representative Snyder of New York, was a direct response to this growing sentiment and the undeniable contributions of Native American soldiers. It was not, however, a sudden, radical departure. It built upon previous, piecemeal legislation that had granted citizenship to specific groups of Native Americans—those who accepted allotments, those who married non-Natives, or those who served in the military prior to 1919. The 1924 Act was significant because it extended citizenship to all remaining non-citizen Native Americans, effectively closing the loophole and making them full citizens by birthright.

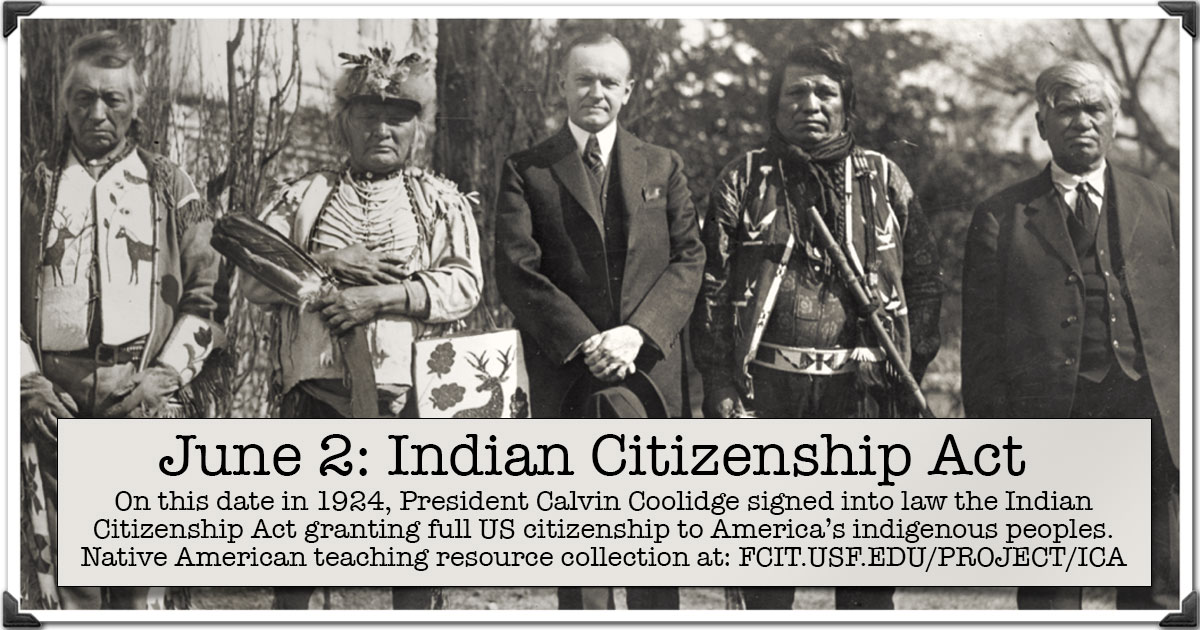

President Calvin Coolidge signed the bill into law, stating, "I am very happy to approve this measure which is a step in the right direction." His words, though seemingly positive, hint at the complexities that would follow. The Act was largely seen by its proponents as the culmination of the assimilation policy—the final step in integrating Native Americans into the American melting pot. Once citizens, it was believed, they would shed their tribal affiliations and become indistinguishable from other Americans.

However, the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act did not instantly grant Native Americans full equality or resolve the deep-seated issues stemming from decades of federal paternalism. In many states, discriminatory laws and practices continued to prevent Native Americans from exercising their newly granted voting rights. Some states, particularly in the Southwest, employed literacy tests, poll taxes, and residency requirements specifically designed to disenfranchise Native voters, a struggle that would continue well into the 1950s and beyond. Arizona, for instance, did not grant Native Americans the right to vote until 1948, and New Mexico followed suit in 1953.

Furthermore, many Native communities viewed the Act with a mix of acceptance and suspicion. While some welcomed the recognition of their belonging to the larger American society, others feared that federal citizenship would undermine their inherent tribal sovereignty. They worried that it was another federal maneuver to dissolve tribal governments and communal landholdings, further eroding their distinct cultural and political identities. Indeed, the Act explicitly stated that "the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property." This clause was crucial in allaying some fears, yet the tension between federal citizenship and tribal sovereignty would remain a defining characteristic of Native American identity.

The Indian Citizenship Act also did not alter the federal government’s trust responsibility for Native lands and resources, nor did it abolish the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Native Americans, even as citizens, remained subject to the unique legal framework of federal Indian law, a framework that continued to treat tribes as distinct political entities while simultaneously overseeing their affairs. This duality—being both citizens of the United States and members of sovereign tribal nations—created a complex legal and political landscape that persists to this day.

The historical context of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 reveals it as a pivotal, yet profoundly nuanced, moment. It was not a simple act of benevolence but a complex outcome of a century of forced assimilation policies, the undeniable contributions of Native American soldiers, and a shifting national consciousness. While it marked a significant legal step towards inclusion, it also highlighted the enduring challenges of cultural preservation, political autonomy, and the full realization of civil rights. The "unfinished promise" of the 1924 Act underscores the ongoing journey of Native American peoples to reconcile their unique histories and sovereign identities with their status as citizens of the United States, a journey that continues to shape the fabric of American society.