Echoes of the Oak: The Enduring Art of Hupa Acorn Bread Making

In the emerald embrace of Northern California’s Trinity River, where ancient redwoods pierce the sky and salmon navigate ancestral currents, resides the Hupa people. For millennia, their lives have been inextricably linked to this bountiful land, a relationship deeply embodied in their traditional foodways. Among these, none holds greater significance or intricate artistry than the preparation of acorn bread – a testament to ingenuity, patience, and profound cultural resilience. Far from a simple recipe, Hupa acorn bread making is a living ceremony, a meticulous process passed down through generations, transforming a seemingly humble nut into the very staff of life.

The Hupa, or Natinixwe (meaning "People of the Place Where the Trails Return"), have maintained a continuous presence in their ancestral territory, adapting and thriving amidst profound historical shifts. Their self-sufficiency was legendary, and the acorn, primarily from the abundant Black Oak (Quercus kelloggii) and Tan Oak (Notholithocarpus densiflorus), formed the cornerstone of their diet. Before the arrival of European settlers, acorns provided up to 50% of the caloric intake for many California tribes, functioning much like wheat or corn did for other agricultural societies. Its high nutritional value – rich in complex carbohydrates, healthy fats, and essential minerals – made it an ideal staple, capable of being stored for long periods.

The journey from a fallen acorn to a nourishing loaf is a masterclass in ethnobotany and food science, beginning with the harvest. In late autumn, when the acorns ripen and drop, Hupa families embark on gathering expeditions. This is not merely collecting; it is a mindful interaction with the forest. Only the best, plumpest acorns are chosen, carefully selected for quality. Elders teach younger generations to respect the trees, leaving enough for wildlife and future harvests, embodying a sustainable approach that predates modern environmentalism.

Once gathered, the acorns are spread out to dry, often on elevated platforms or in baskets, allowing them to cure and prevent spoilage. This crucial step reduces moisture content, making them easier to shell and ensuring they can be stored for years, providing food security through lean times. The shelled acorns are then ready for the laborious but essential process of grinding.

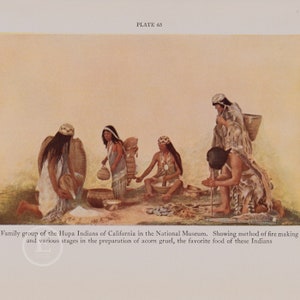

Traditionally, this task fell primarily to women, who would use a stone mortar and pestle, often beautifully crafted from local stone. The rhythmic thud of the pestle against the mortar was a common sound in Hupa villages, a sonic backdrop to daily life. This process pulverizes the hard acorn meat into a fine, flour-like meal. Modern adaptations might include electric grinders, but many practitioners still prefer the traditional method, not just for authenticity but for the meditative quality and the connection it fosters to ancestral practices. "The sound of the stone, the feel of the meal between your fingers – it connects you directly to our grandmothers," explains a Hupa cultural bearer, emphasizing the sensory and spiritual dimensions of the process.

However, acorn flour in its raw state is bitter and toxic due to high concentrations of tannic acid. This is where the true genius of Hupa food preparation shines: the leaching process. This intricate method removes the tannins, rendering the flour palatable and safe. The most traditional Hupa method involves creating a shallow basin in clean sand, often near a stream or river. The finely ground acorn meal is carefully spread into this basin. Then, cold water is slowly poured over the flour, allowing it to percolate through the meal and carry away the soluble tannins.

This is a delicate operation, requiring immense patience and skill. Too fast, and the flour washes away; too slow, and the tannins remain. The water must be changed repeatedly, sometimes for several hours or even a full day, until the flour is completely "sweetened." Periodically, a small pinch of the wet flour is tasted. The absence of bitterness signals completion. This method is not just efficient; it’s environmentally sound, using natural filtration and returning the tannins to the earth without chemical intervention. Other leaching methods might involve placing the flour in woven bags and submerging them in running water or repeatedly rinsing in a basket.

Once leached, the wet acorn meal is ready for cooking. The Hupa traditionally prepared their acorn bread in various forms, often as a thick gruel or mush, but also as a more solidified "bread" or cake. One common method involved heating stones in a fire until they were glowing hot. The wet acorn meal would then be placed into a tightly woven basket, often a twined cooking basket renowned for its watertight properties. The hot stones, carefully cleaned of ash, would then be plunged directly into the meal, stirring continuously with a wooden paddle. The heat from the stones would quickly cook the meal, thickening it into a rich, dark, and nutritious porridge. This method required precise timing and expertise to avoid burning the meal or shattering the stones.

Another preparation involved baking the meal in pit ovens or on hot stones, forming flat cakes. The consistency could vary from a thick, spoonable soup to a firm, sliceable loaf, depending on the desired outcome and the occasion. The resulting acorn bread has a distinct, earthy flavor, subtly sweet and nutty, a taste deeply ingrained in Hupa memory and identity.

Beyond its nutritional value, acorn bread holds profound cultural and spiritual significance for the Hupa. It is a symbol of self-sufficiency, a direct link to their ancestors who thrived on this food for millennia. The entire process, from gathering to cooking, is imbued with ritual and respect, fostering a deep connection to the land and its resources. The collective effort involved in gathering and preparing acorns also strengthens community bonds, with knowledge and skills passed down through generations, reinforcing familial and tribal identity.

The elder women, with hands weathered by decades of practice, are the living libraries of this knowledge. They are the keepers of the traditions, the teachers who ensure that the intricate details of grinding, leaching, and cooking are not lost. "Making acorn bread is more than just making food; it’s an act of cultural preservation," notes a Hupa elder, "Every step is a prayer, a way of honoring those who came before us and ensuring our future." It is often served at ceremonies, tribal gatherings, and family meals, a staple that nourishes both body and spirit.

In recent decades, there has been a significant revitalization of traditional foodways among the Hupa and other California tribes. Younger generations are actively seeking out and learning these ancient skills, understanding that food is a powerful conduit for cultural identity and sovereignty. Language immersion programs, cultural centers, and tribal schools now often incorporate acorn processing into their curricula, ensuring the knowledge continues to thrive.

However, the practice of acorn bread making faces modern challenges. Climate change, with its unpredictable weather patterns and increased wildfire frequency, threatens the health of oak forests. Access to traditional gathering grounds can also be an issue, as private land ownership and resource management policies sometimes restrict tribal members. Furthermore, the loss of elders means a race against time to document and transmit their invaluable wisdom before it fades.

Despite these obstacles, the Hupa continue to embrace their ancestral foods. The rhythmic thud of the pestle, the careful watch over the leaching sand basin, the shared meal of warm acorn bread – these are not just echoes of the past. They are vibrant, living traditions that affirm the Hupa people’s enduring connection to their land, their history, and their future. Hupa acorn bread making is more than a culinary art; it is a powerful statement of resilience, a delicious symbol of an unbroken cultural lineage that continues to nourish and define a proud people.