The Crucible of Sovereignty: How Reservation Life Reshaped Tribal Governance

Before the relentless westward expansion of the United States, Indigenous nations across North America boasted a rich tapestry of political innovation. From the consensus-driven councils of the Haudenosaunee to the highly centralized leadership of the Cherokee, the democratic principles of the Lakota, and the clan-based governance of the Navajo, tribal communities exercised inherent sovereignty over vast territories. Their systems were diverse, deeply rooted in spiritual beliefs, communal responsibilities, and an intimate connection to the land. The imposition of reservation life, however, shattered these foundations, initiating a century-long crucible that profoundly reshaped, challenged, and ultimately strengthened the very nature of tribal governance.

The genesis of this transformation lay in the stark reality of forced relocation and confinement. As the U.S. government consolidated its control over Native lands, tribes were shunted onto ever-shrinking parcels, often far from their ancestral homes and traditional resources. This was not merely a change of address; it was a deliberate act of cultural and political subjugation, designed to break tribal autonomy and assimilate Native peoples into the dominant American society. The architect of this policy, often driven by a paternalistic view of Native Americans as "wards of the state," sought to dismantle existing political structures and replace them with systems more amenable to federal control.

One of the most immediate and devastating impacts was the systematic undermining of traditional authority. Prior to reservations, leaders earned their status through a combination of wisdom, spiritual power, military prowess, oratorical skill, and a proven commitment to their people’s welfare. Their authority was often consensual, derived from the respect of the community, rather than coercive. The U.S. government, through its Indian Agents, deliberately bypassed these legitimate leaders. Instead, agents often appointed compliant individuals – often pejoratively called "paper chiefs" – who lacked traditional legitimacy but were willing to enforce federal policies, distribute rations, and sign treaties. This created deep divisions within communities, fostering resentment and confusion over who truly held power. As historian Angie Debo noted, "The Indian agent was a law unto himself, often a petty tyrant who ruled his reservation with an iron hand, accountable to no one but his distant superiors."

The economic disruption wrought by reservation life further eroded traditional governance. Stripped of their hunting grounds, fishing rights, and agricultural lands, tribes lost their economic self-sufficiency. They became dependent on government rations, supplies, and annuities, transforming their vibrant, self-sustaining economies into impoverished client states. This dependency shifted the locus of power away from traditional councils and towards the Indian Agent, who controlled the flow of essential goods. Decisions that once rested with tribal elders – regarding resource allocation, economic development, and community welfare – were now dictated by an external authority, further marginalizing traditional leaders and stifling indigenous decision-making processes.

The U.S. government’s assimilationist agenda also targeted the very fabric of tribal culture, which was intrinsically linked to governance. Boarding schools forcibly removed children from their families, forbidding the speaking of Native languages and the practice of traditional ceremonies. These policies aimed to erase the cultural underpinnings that gave meaning and legitimacy to traditional governance structures. Without the shared language, spiritual practices, and communal rituals that reinforced social cohesion and leadership roles, the internal mechanisms of governance became fragmented and weakened.

A pivotal moment in the evolution of tribal governance came with the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. Spearheaded by Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier, the IRA represented a significant shift from the previous assimilationist policies, aiming to promote tribal self-governance and economic development. However, it was a double-edged sword. While it provided a framework for tribes to adopt written constitutions and elect tribal councils, it largely imposed a Euro-American model of government – complete with a separation of powers and majority-rule elections – that often clashed with existing indigenous political traditions.

For many tribes, the IRA was a welcome opportunity to rebuild their communities and assert a degree of control. For others, it was viewed with suspicion, seen as yet another attempt by the federal government to dictate how they should govern themselves. The Navajo Nation, for example, famously rejected the IRA, fearing it would further undermine their traditional clan-based system and consolidate power in the hands of a few. This rejection underscored a critical point: the IRA, despite its progressive intentions, did not necessarily restore traditional governance; rather, it introduced a new, federally sanctioned model that tribes had to either adopt, adapt, or resist.

The IRA’s implementation also exacerbated existing factionalism. Tribes often found themselves divided between "traditionalists" who sought to preserve ancient ways and "progressives" who embraced the new, federally recognized system. These divisions, often fueled by historical grievances and differing visions for the future, could lead to contentious elections, legal disputes, and internal instability, making unified governance challenging. Yet, despite these challenges, the IRA did provide a legal framework that allowed tribes to establish formal governments, manage some of their own affairs, and begin the long process of rebuilding their institutional capacity.

The mid-20th century brought another assault on tribal sovereignty with the "Termination Era" (1950s-1960s). This policy aimed to end the federal government’s recognition of tribes and their special relationship, effectively dissolving tribal governments and distributing tribal assets. Though largely a failure, resulting in immense hardship for terminated tribes, it further demonstrated the precariousness of tribal governance and the constant threat of federal interference.

The tide began to turn with the "Self-Determination Era," ushered in by the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This landmark legislation empowered tribes to contract with the federal government to administer their own programs and services, rather than having them managed by federal agencies. This marked a profound shift, recognizing tribal governments as capable and legitimate entities. It fostered the development of sophisticated tribal bureaucracies, legal departments, and economic development corporations. Tribes began to exercise their inherent sovereignty more robustly, negotiating directly with federal and state governments, establishing tribal courts, and building modern infrastructures.

Today, tribal governance is a complex tapestry woven from traditional values, federally imposed structures, and modern adaptations. Many tribal nations have revised their IRA constitutions or developed new ones that better reflect their unique cultural values and aspirations. The rise of tribal enterprises, particularly gaming, has provided unprecedented economic resources, allowing tribes to fund their own governmental services, invest in infrastructure, and reduce their reliance on federal appropriations. This economic independence has been a powerful tool in strengthening self-governance, demonstrating that economic sovereignty is often a prerequisite for political sovereignty.

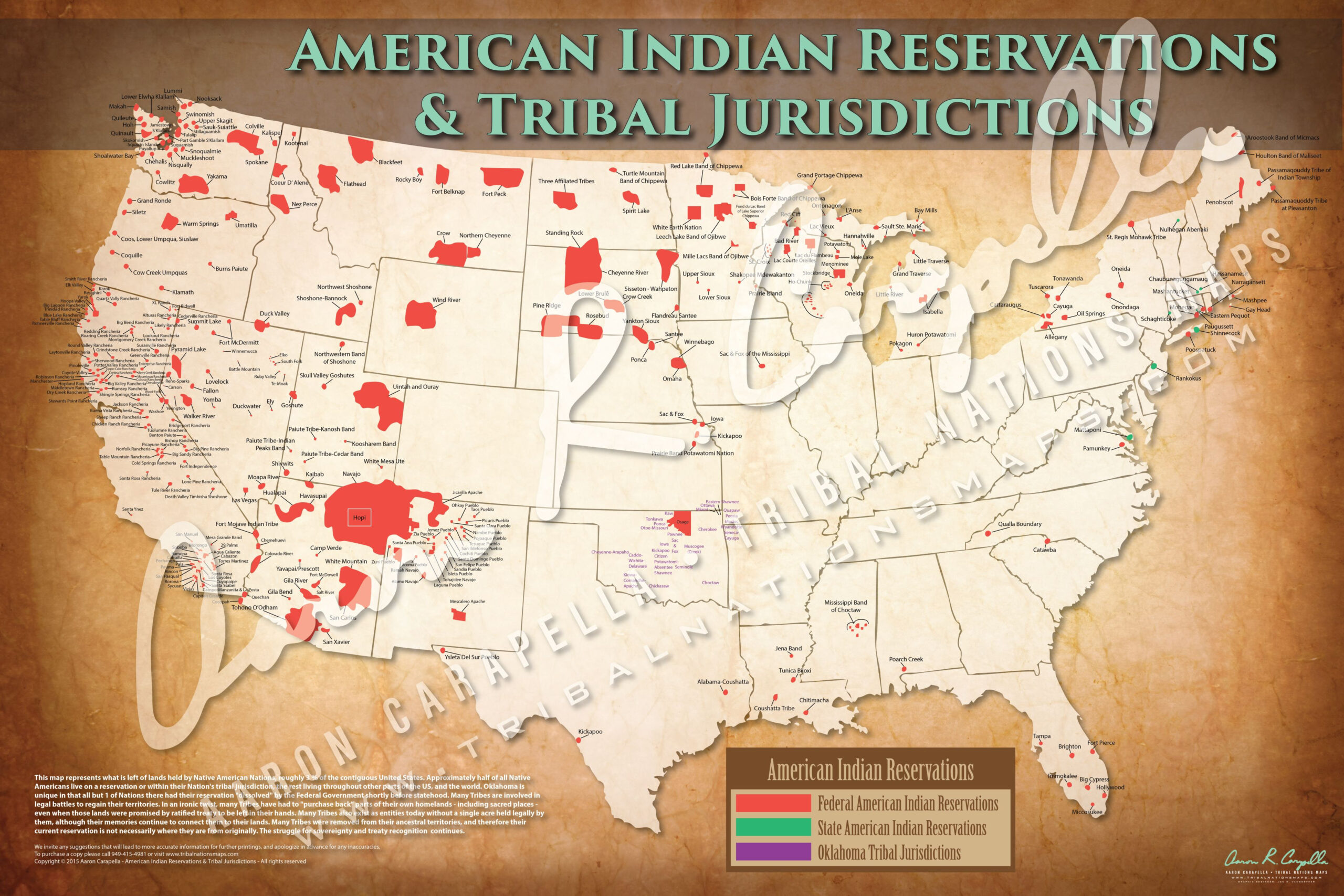

Yet, the legacy of reservation life continues to shape tribal governance. Issues like factionalism, the balancing of traditional customs with modern legal frameworks, and the ongoing struggle for jurisdictional clarity with state and federal governments remain persistent challenges. The imposed boundaries of reservations, often arbitrary and cutting across traditional territories, continue to impact land management, resource allocation, and inter-tribal relations.

In conclusion, reservation life subjected tribal governance to an unprecedented crucible of change. It began with a deliberate campaign to dismantle traditional authority, impose foreign political models, and foster economic dependency. The IRA, while a step towards self-governance, introduced its own set of challenges by imposing external structures. However, through immense resilience, adaptation, and unwavering commitment to their distinct identities, Native nations have not only survived these assaults but have emerged with renewed strength. Modern tribal governments, while undeniably shaped by this historical journey, are vibrant, evolving institutions that continue to assert their inherent sovereignty, weaving together the wisdom of their ancestors with the demands of the 21st century to chart their own course forward. The story of tribal governance on reservations is a testament to the enduring spirit of self-determination against overwhelming odds.

+-.jpg)