Echoes Across the Land: The Rich Tapestry of Ancient Native American Communication

The vast and diverse landscapes of North America, from the Arctic tundra to the sun-baked deserts and lush eastern forests, were home to hundreds of distinct indigenous nations long before European contact. For millennia, these societies thrived, building complex social structures, spiritual systems, and intricate trade networks. At the heart of their endurance and evolution lay sophisticated communication systems – a rich tapestry woven from spoken word, visual symbols, auditory signals, and tangible records. To understand how ancient Native Americans communicated is to peel back layers of history and appreciate the ingenuity and adaptability that allowed diverse cultures to flourish, connect, and endure.

The Spoken Word: A Symphony of Tongues

At the bedrock of all human interaction is language, and ancient North America was a linguistic wonderland. Estimates suggest that at the time of European arrival, there were between 300 and 500 distinct indigenous languages spoken, belonging to dozens of language families as diverse as those found across all of Europe or Asia. From the Algonquian and Iroquoian languages of the East, to the Siouan and Caddoan tongues of the Plains, the Athabaskan and Uto-Aztecan families of the Southwest, and the countless unique languages of the Pacific Northwest, each language was a complex system of sounds, grammar, and vocabulary reflecting the worldview and environment of its speakers.

These languages were not merely tools for basic needs; they were the vessels for elaborate oral traditions. Storytelling was paramount, serving as the primary means of transmitting history, spiritual beliefs, ethical codes, practical knowledge (hunting, plant medicine, navigation), and cultural values across generations. Elders, often revered as living libraries, held vast amounts of knowledge in their memories, recounting epic myths, origin stories, and tribal histories that could take days to fully narrate. These oral histories were meticulously preserved through repeated telling, often in ceremonial contexts, ensuring their accuracy and continuity. The cadence, rhythm, and intonation of the storyteller were as crucial as the words themselves, imbuing narratives with power and emotional resonance. The very act of listening was an active form of communication, fostering community and collective identity.

Messages in Motion and Stone: Visual Communication

Beyond the spoken word, ancient Native Americans developed a remarkable array of visual communication methods, designed to transcend linguistic barriers and convey information across vast distances or through time.

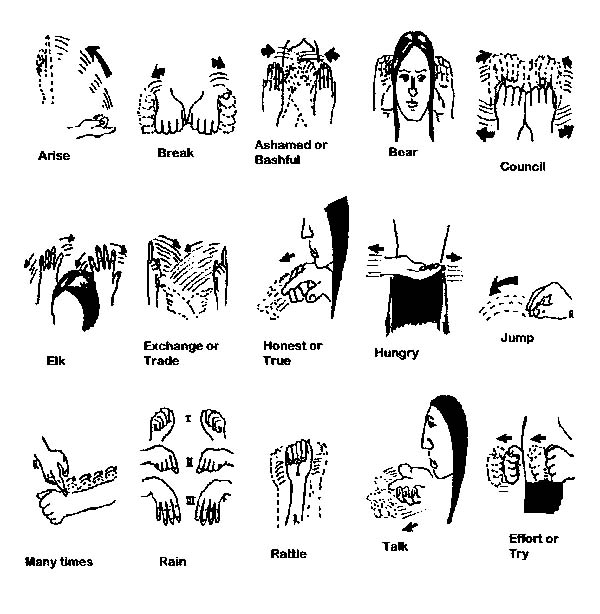

Perhaps one of the most widely recognized forms is Plains Indian Sign Language (PISL). Developed and refined over centuries, particularly among the mobile hunting societies of the Great Plains, PISL was not a simple set of gestures but a sophisticated, complete language capable of expressing complex ideas, emotions, and narratives. It allowed individuals from different linguistic groups – Sioux, Cheyenne, Crow, Arapaho, Comanche, and others – to communicate effectively for trade, diplomacy, hunting, and even warfare. Scholars note its remarkable grammatical structure and extensive vocabulary, proving its utility and sophistication in a region characterized by immense linguistic diversity. A flick of the wrist, a sweep of the arm, or the precise positioning of fingers could convey everything from "buffalo" to "I come in peace" or "where is the water?"

Rock art, in the form of petroglyphs (carvings into rock) and pictographs (paintings on rock), represents some of the most enduring ancient communications. Found across the continent, these artistic expressions served multiple purposes: recording historical events, marking territorial boundaries, depicting spiritual visions, illustrating astronomical observations, or serving as mnemonic devices for oral traditions. The images – human and animal figures, geometric patterns, celestial bodies – are not always easily deciphered today, as their meaning was often specific to the culture, time, and even the individual who created them, sometimes intended only for spiritual entities or future generations with shared cultural understanding. For instance, the Anasazi and Fremont cultures of the Southwest left behind thousands of enigmatic figures that continue to fascinate archaeologists, hinting at complex belief systems and historical narratives etched into the very landscape.

More ephemeral but equally vital were smoke signals. While often romanticized, smoke signals were a practical method for long-distance communication, particularly in open terrain. A column of smoke could alert distant camps to danger, signal the location of game, or indicate the approach of friends or foes. The meaning was conveyed not just by the presence of smoke, but by its patterns – puffs, pauses, and duration – understood through pre-arranged codes among specific groups. Their effectiveness, however, was limited by weather conditions and the relative simplicity of the messages they could convey.

Body art, clothing, and regalia also played a significant communicative role. Adornments, tattoos, face paint, and the designs woven into textiles or beaded onto garments were powerful visual cues. They could signify tribal affiliation, social status, achievements (e.g., war honors), spiritual beliefs, or readiness for ceremony or battle. A particular feather, a specific shell, or a unique pattern on a blanket could instantly communicate a wealth of information about the wearer’s identity and life story to those who understood the cultural lexicon.

Auditory Signals: Drums, Flutes, and Voices

Beyond the direct spoken word, ancient Native Americans employed a range of auditory signals to communicate over distance and within community gatherings.

The drum was, and remains, a central element in many Native American cultures. More than just a musical instrument, drums were powerful communicators. Their rhythms could set the pace for dances, accompany songs, signal the start of ceremonies, or even convey urgent messages across distances. Specific drum patterns could alert a village to an approaching war party, call people to a gathering, or celebrate a successful hunt. The deep, resonant throb of a drum could carry for miles through forests or across plains, reaching ears that were attuned to its particular language.

Flutes often served a more personal and spiritual communicative purpose. Crafted from wood or bone, their haunting melodies were used for courtship, personal reflection, spiritual ceremonies, and storytelling. While not conveying explicit messages in the way a drum might, the emotion and cultural significance embedded in flute music communicated deeply felt human experiences and spiritual connections.

Voice calls and whoops were also highly developed for long-distance communication. Hunters might use specific calls to coordinate during a chase, or sentinels might emit distinct cries to warn of danger. These were not random shouts but often highly stylized vocalizations, understood within a specific community, capable of conveying urgency, location, or the type of threat.

Tangible Records: Wampum and Winter Counts

While not "writing" in the European alphabetic sense, several ancient Native American cultures developed sophisticated systems for recording information and commemorating events using tangible objects.

Wampum belts are perhaps the most famous example from the Northeast. Crafted from the polished shells of quahog and whelk, these white and purple beads were woven into intricate patterns on belts or strings. Wampum was not currency, as often misunderstood, but a highly valued medium for recording treaties, agreements, historical events, and important messages. The patterns and arrangements of the beads served as mnemonic devices, aiding the memory of the "wampum keepers" who could "read" the belts, recounting the history and agreements they represented. The Iroquois Confederacy, in particular, utilized wampum extensively in their sophisticated political and diplomatic processes, solidifying alliances and codifying laws through these symbolic objects. A wampum belt served as a physical testament to a spoken agreement, giving it weight and longevity.

On the Great Plains, tribes like the Lakota, Kiowa, and Mandan maintained Winter Counts (Waniyetu Wowapi). These were calendrical histories, typically painted on buffalo hides or cloth, where a single pictograph or symbol represented the most significant event of an entire year. Each year was depicted sequentially, forming a spiral or linear narrative that could span a century or more. The keeper of the Winter Count would use these symbols as memory aids to recount the detailed history of the tribe, from battles and epidemics to migrations and notable births. They were not merely chronicles but communal memories, allowing generations to connect with their past.

Some scholars also point to the potential use of knotted cords for mnemonic purposes or counting, similar in concept, though not in complexity, to the South American Inca quipu. While widespread evidence for highly complex knotted-cord record-keeping systems like the quipu in North America is scarce, various groups used simple knotted cords for counting days, recording quantities, or aiding memory in storytelling.

The Enduring Legacy

The communication systems of ancient Native Americans were far from "primitive." They were ingenious, adaptable, and deeply interwoven with their spiritual beliefs, social structures, and the natural environment. They demonstrate a profound understanding of how to transmit complex information across linguistic barriers, vast distances, and the span of generations, utilizing every available medium – the human voice, the body, natural materials, and the very landscape itself.

From the resonant echoes of a drum across the plains to the silent eloquence of a wampum belt, from the enduring stories etched in stone to the vibrant narratives passed down through generations of storytellers, these methods allowed ancient Native American societies to thrive for thousands of years. Understanding this rich tapestry of communication not only deepens our appreciation for their ingenuity but also offers profound insights into the human capacity for connection, adaptation, and the enduring power of shared meaning. These echoes across the land continue to resonate, reminding us of a complex and vibrant past that shaped the continent long before written history began.