The Long Shadow of Dispossession: A History of Native American Removal Policies

The history of the United States is often told as a triumphant march of progress, a narrative of expansion and liberty. Yet, beneath this veneer lies a stark, brutal chapter: the systematic dispossession and forced removal of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands. This wasn’t a series of isolated incidents, but a complex, evolving, and often legally sanctioned policy that shaped the continent, fueled national expansion, and left an indelible scar on generations of Native Americans. From the earliest colonial encounters to the dawn of the 20th century, the thread of removal—driven by land hunger, racial prejudice, and a paternalistic vision of "civilization"—runs dark and deep through American history.

Early Encounters and the Seeds of Conflict (Colonial Era – Early Republic)

The arrival of European colonists in North America immediately set the stage for conflict over land. Initially, Native nations were often seen as sovereign entities, capable of treaties and alliances. However, as colonial populations grew and their insatiable demand for land intensified, this perspective shifted. Early policies often involved coerced land sales, military conquest, and the exploitation of inter-tribal rivalries.

Following the American Revolution, the nascent United States inherited and intensified this land hunger. President Thomas Jefferson, while often espousing a vision of Native Americans integrating into American society as farmers, simultaneously envisioned their eventual removal beyond the Mississippi River. He famously stated in 1803 that Indigenous people should be encouraged "to exchange lands which they have a right to sell, and we have a right to buy, for others more to their taste & convenience." This seemingly benign offer often masked a coercive strategy, as Indigenous communities, weakened by disease and military pressure, found their options dwindling. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 dramatically expanded the land available for white settlement, further fueling the idea that a vast, empty "Indian Territory" in the west could serve as a permanent solution.

The Jacksonian Era: Formalizing Forced Removal (1820s-1840s)

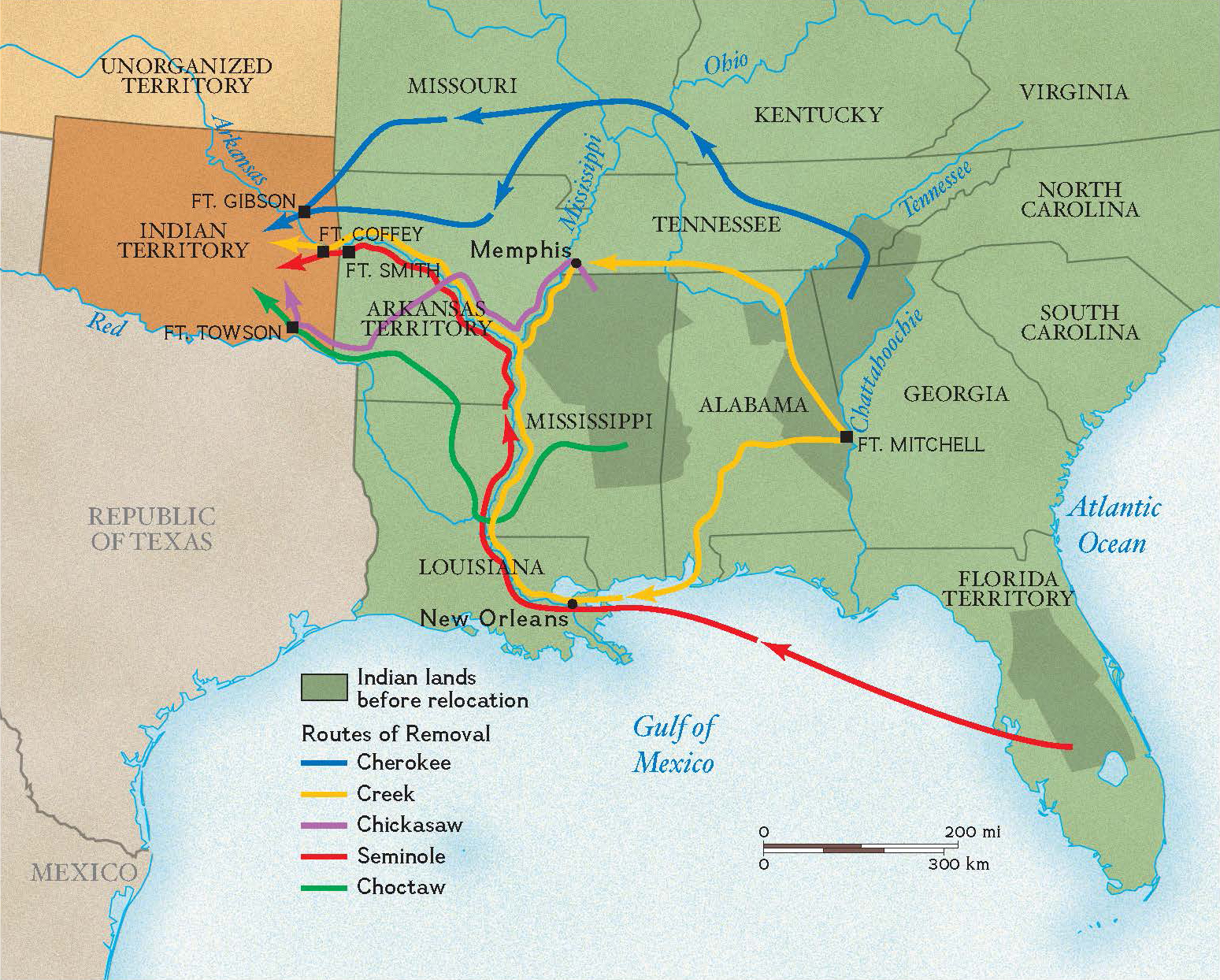

The push for removal reached its zenith under President Andrew Jackson, a figure whose legacy is inextricably linked to the policy. By the 1820s, the "Five Civilized Tribes"—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole—had adopted many aspects of American culture, including written languages, constitutional governments, and farming techniques, largely in an attempt to retain their lands in the southeastern United States. Yet, their progress only intensified the desires of white settlers and the state of Georgia, which coveted their rich cotton lands and gold deposits.

The legal battles that ensued were pivotal. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that the Cherokee constituted a "domestic dependent nation," not a foreign state, and thus lacked the standing to sue in federal court. However, in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), Marshall sided with the Cherokee, declaring that Georgia law had no force over Cherokee lands and that the tribe possessed inherent sovereignty. President Jackson, famously dismissive of the ruling, is often quoted as saying, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!" This defiant stance effectively greenlit Georgia’s incursions.

The culmination of this era was the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Passed by a narrow margin, it authorized the President to negotiate treaties for the removal of Native American tribes from their ancestral lands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi River. While ostensibly voluntary, the "negotiations" were often conducted with minority factions of tribes, or under extreme duress, leading to treaties that were not recognized by the majority of the tribal governments.

The most infamous consequence was the Trail of Tears. In 1838, under President Martin Van Buren, the U.S. Army, led by General Winfield Scott, forcibly removed approximately 16,000 Cherokee people from their homes in Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, and North Carolina. Marched westward in brutal conditions, often without adequate food, clothing, or shelter, over 4,000 Cherokee men, women, and children perished from disease, starvation, and exposure. Similar forced removals affected the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole, though the latter waged a series of costly wars in Florida to resist. The Trail of Tears remains a searing symbol of American betrayal and human suffering.

Westward Expansion and the Reservation System (Mid-19th Century)

As the nation embraced the concept of Manifest Destiny—the belief in America’s divinely ordained right to expand westward—the policies of removal continued, albeit shifting in form. The discovery of gold in California, the construction of transcontinental railroads, and the Homestead Act of 1862 all accelerated the drive for land in the West. This led to a series of "Indian Wars" and further displacement of Plains tribes, often culminating in massacres like Sand Creek (1864) and Wounded Knee (1890).

Rather than outright removal to a distant territory, the mid-to-late 19th century saw the establishment of the reservation system. Initially conceived as temporary holding grounds or places where Native people could be "civilized" away from white society, reservations quickly became permanent, often impoverished enclaves. Tribes were forced onto lands that were frequently marginal, unsuitable for traditional hunting or farming, and far from their spiritual homes. The federal government, through the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), exerted immense control over nearly every aspect of reservation life, from governance to resource allocation, fostering dependency and undermining traditional leadership.

The Assimilation Era: "Kill the Indian, Save the Man" (Late 19th – Early 20th Century)

Even on reservations, the pressure to dismantle Native cultures persisted. The late 19th century witnessed a concerted effort at forced assimilation, driven by the belief that the "Indian problem" could be solved by transforming Native Americans into self-sufficient, land-owning, Christian citizens. This era is perhaps best encapsulated by the infamous philosophy of General Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School: "Kill the Indian, Save the Man."

The primary legislative tool for this policy was the Dawes General Allotment Act of 1887. This act sought to break up tribally held communal lands into individual plots (allotments) for Native American families, with the surplus land then sold off to non-Native settlers. The stated goal was to promote individualism and farming, but its actual effect was catastrophic. Between 1887 and 1934, Native American landholdings plummeted from 138 million acres to 48 million acres, with much of the "surplus" land falling into non-Native hands. The Dawes Act also severely disrupted traditional communal governance and economies.

Parallel to land allotment were the Indian boarding schools. Children, often forcibly removed from their families, were sent to these institutions, sometimes hundreds or thousands of miles away from home. At schools like Carlisle, students were stripped of their traditional clothing, had their hair cut, were forbidden to speak their native languages, and were often subjected to harsh discipline, manual labor, and cultural indoctrination. The traumatic legacy of these schools—which included widespread physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, and the systematic suppression of Indigenous identity—continues to impact Native communities today.

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 granted U.S. citizenship to all Native Americans born in the United States. While seemingly a step towards equality, it was often enacted without tribal consent and complicated the already tenuous relationship between tribal sovereignty and federal authority.

The Termination Era and a Path to Self-Determination (Mid-20th Century – Present)

Following World War II, a new, albeit short-lived, policy emerged: Termination. Driven by a desire to reduce federal spending and integrate Native Americans fully into mainstream society, Congress passed a series of acts in the 1950s that aimed to end the federal government’s trust relationship with certain tribes, effectively terminating their tribal status and withdrawing federal services. This policy was disastrous, leading to increased poverty, loss of land, and the collapse of tribal infrastructure for those tribes subjected to it. Concurrently, "relocation" programs encouraged Native Americans to move from reservations to urban areas, often finding themselves ill-prepared for city life and facing discrimination.

However, the late 1960s and 1970s marked a turning point, fueled by the Civil Rights Movement and growing Native American activism (e.g., the American Indian Movement, the occupation of Alcatraz). The tide began to turn towards self-determination. President Richard Nixon, in a landmark speech in 1970, repudiated the termination policy and called for a new era of tribal self-governance. This culminated in the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, which allowed tribes to take over the administration of federal programs and services previously run by the BIA.

Today, while challenges persist—including poverty, historical trauma, and ongoing struggles over land rights and environmental justice—Native American nations are actively engaged in rebuilding and strengthening their communities. They assert their sovereignty, develop their economies, revive their languages and cultures, and advocate for greater recognition and justice.

Conclusion

The history of Native American removal policies is a testament to the devastating power of conquest, prejudice, and a relentless pursuit of land. It is a story of broken treaties, forced marches, cultural destruction, and systemic injustice. Yet, it is also a story of immense resilience, of Indigenous peoples who, despite generations of hardship, have endured, adapted, and continue to fight for their rights, their cultures, and their rightful place on this continent. Understanding this complex history is not merely an academic exercise; it is essential for comprehending the foundational injustices of the American past and for forging a more equitable future. The long shadow of dispossession reminds us that progress, if it is to be truly just, must confront and reconcile with its own uncomfortable truths.