Echoes in the Land: The Enduring Legacy of Native American Place Names

Every map, every road sign, every town and city name tells a story. But beneath the familiar English, French, or Spanish appellations that dot the landscape of North America lies a deeper, older narrative—a linguistic tapestry woven by the continent’s first inhabitants. The history of Native American place names is not merely a catalogue of exotic-sounding words; it is a living archive, a testament to intricate relationships with the land, profound cultural knowledge, and the enduring resilience of Indigenous peoples in the face of centuries of colonial erasure.

To truly understand the "history" of these names, one must first appreciate the distinct worldview from which they emerged. Unlike European traditions, which often named places after monarchs, saints, or distant homelands, Indigenous naming practices were deeply rooted in observation, utility, and narrative. A Native American place name was rarely arbitrary; it was a descriptor, a warning, a historical marker, a spiritual reference, or a guidepost embedded with layers of meaning. These names were, in essence, compact poems or short stories, reflecting the physical attributes of the landscape, the events that transpired there, the resources found, or the spiritual significance of a particular site.

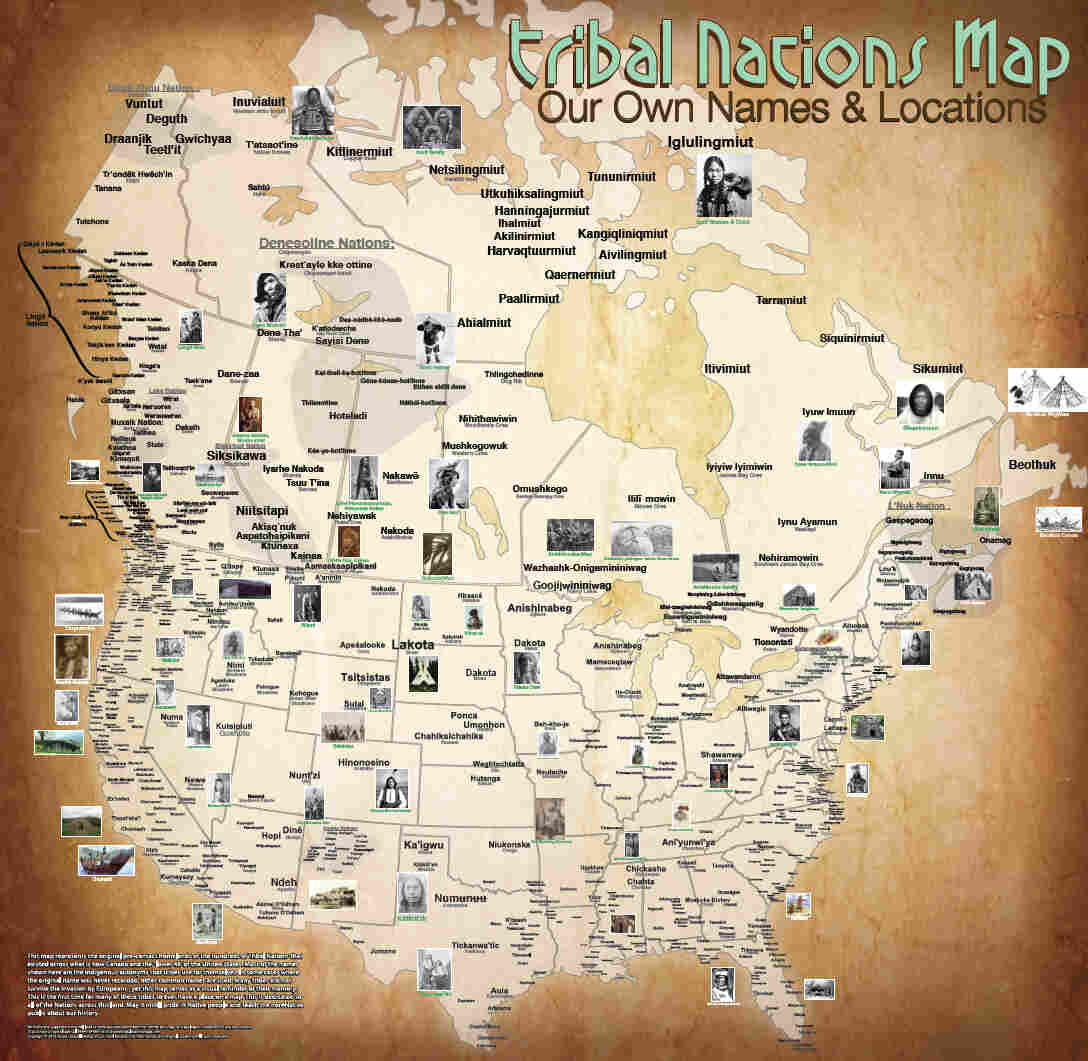

Consider the sheer linguistic diversity that once thrived across the continent. Hundreds of distinct languages, belonging to dozens of language families, each contributed to a rich lexicon of place names. From the Algonquian languages of the Northeast to the Siouan tongues of the Great Plains, the Athabaskan languages of the Southwest, and the countless others in between, each nation possessed its own way of articulating its connection to its ancestral lands. This diversity meant that a single geographical feature, like a river or a mountain, might have been known by numerous different names to different neighboring tribes, each reflecting their unique perspective and interaction with that feature.

The arrival of European explorers, traders, and settlers marked a pivotal, and often destructive, turning point for Indigenous place names. Early encounters were characterized by a mix of phonetic approximation, cultural misunderstanding, and deliberate renaming. European ears, unaccustomed to the phonologies of Native languages, often struggled to accurately transcribe the sounds they heard. What resulted were often corrupted, simplified, or entirely misinterpreted versions of the original names.

Take, for example, the mighty Mississippi River. Its name is an anglicized version of the Algonquian word "Misi-ziibi," meaning "Great River" or "Father of Waters." This translation, while fitting, loses the nuanced phonetics and the full resonance of the original. Similarly, Ohio, derived from an Iroquoian word "Ohi:yo’," translates to "Great River" or "Beautiful River," capturing the essence but flattening the linguistic texture. Chicago, a name now synonymous with a bustling metropolis, comes from a Miami-Illinois word, "Shikaakwa," meaning "wild onion place," a humble but deeply descriptive origin reflecting the area’s natural abundance.

Beyond phonetic challenges, cultural chasms often led to misinterpretations. A Native speaker might point to a significant feature and utter a phrase describing an event that happened there, or a characteristic of its fauna, only for the European listener to assume that phrase was the name of the place. This sometimes resulted in amusing or nonsensical translations. The famous Walla Walla in Washington State is believed to be from a Sahaptian word meaning "place of many waters," a poetic and accurate description of the region’s rivers and springs.

However, many Native American place names did not survive this initial contact. As European settlements grew and colonial powers asserted dominance, a systematic process of renaming began. Places were often rechristened to honor European monarchs (e.g., Virginia, Georgia), colonial figures (e.g., Washington, Pennsylvania), or to evoke nostalgia for European homelands (e.g., New York, New England). This act of renaming was not merely practical; it was a powerful assertion of territorial claim and cultural supremacy, effectively erasing Indigenous presence from the land’s nomenclature. The vast majority of places on the East Coast, the first area of sustained European settlement, bear little trace of their original Indigenous names, swallowed by the tide of colonial cartography.

Yet, many names persisted, particularly in regions where Native influence remained strong for longer, or where the sheer beauty and descriptiveness of the Indigenous names were undeniable. The American West, settled later and often with more direct interaction with diverse Indigenous nations, retains a higher concentration of Native place names. States like Idaho (Shoshone: "Gem of the Mountains" or "Light on the Mountains"), Utah (Ute: "People of the Mountains"), Wyoming (Algonquian: "large plains" or "at the big river flat"), and Kansas (Kansa: "people of the south wind") bear Indigenous names as their very identity.

National parks, often established in areas of immense natural beauty, frequently preserved Indigenous names, sometimes with a romanticized or slightly altered flavor. Yosemite National Park, for instance, is derived from a Miwok word "Yo’hem-ite," referring to the name of a local grizzly bear clan, often mistakenly translated as "grizzly bear" or "those who kill." The park’s iconic Half Dome and El Capitan also have original Miwok names, like "Tis-sa-ack" and "To-tock-ah-nula," that speak to their spiritual and practical significance. The grandeur of Denali, North America’s highest peak, was finally officially restored from "Mount McKinley" in 2015, reclaiming its Koyukon Athabaskan name meaning "the tall one" or "the great one"—a powerful symbol of revitalization.

The enduring presence of Native American place names is a testament not only to their inherent descriptive power but also to the literary and cultural currents that sometimes favored them. In the 19th century, figures like James Fenimore Cooper, while often perpetuating stereotypes, also popularized Native American names in his "Leatherstocking Tales," lending them an aura of exoticism and romantic wilderness that appealed to a nascent American identity distinct from its European roots. This romanticization, while problematic in its origins, inadvertently helped to cement some Indigenous names into the national consciousness.

Today, the history of Native American place names is experiencing a powerful resurgence, driven by Indigenous language revitalization efforts, movements for historical accuracy, and a broader societal recognition of the importance of decolonization. Tribal nations are actively working to restore original names to places that were renamed by settlers or the federal government. This isn’t just about changing a label; it’s about reclaiming identity, challenging the myth of terra nullius (empty land), and reasserting Indigenous sovereignty and connection to ancestral territories.

The Mni Sota Makoce ("land where the waters reflect the sky") is now the state of Minnesota, but efforts are underway to educate the public on the original Dakota name and its profound meaning. In Hawaii, a similar movement has seen many Hawaiian place names, often corrupted or replaced during the period of American annexation, being restored and celebrated. These efforts are crucial because place names are not static historical artifacts; they are living components of Indigenous languages and cultures. When a name is lost or forgotten, a piece of that culture’s narrative, its connection to its homeland, and its understanding of the world also diminishes.

Diné Bikéyah is the Navajo Nation’s name for their homeland, meaning "Navajo land." This name is not just a geographic designation but a statement of identity, history, and spiritual belonging. Learning these original names, and understanding their meanings, offers a profound entryway into Indigenous worldviews, ecological knowledge, and historical experiences. It compels us to look beyond the surface of a map and see the layers of human history etched into the very ground we stand on.

The story of Native American place names is a microcosm of the larger story of Indigenous-colonial relations in North America. It is a narrative of beauty and practicality, of linguistic diversity and cultural depth, but also of erasure, misunderstanding, and resilience. As we navigate a landscape dotted with names like Susquehanna ("muddy river"), Tacoma ("mother of waters"), Milwaukee ("good land"), or Cheyenne ("people of a foreign language" or "red talkers"), we are presented with an opportunity. It is an invitation to listen more closely to the echoes in the land, to acknowledge the rich, complex histories that precede us, and to honor the enduring legacy of those who first named this continent. By doing so, we not only enrich our understanding of the past but also foster a more inclusive and respectful relationship with the land and all its peoples in the present and future.