The Enduring Wisdom of the Great Lakes: Unearthing Original Peoples’ Cultural Teachings

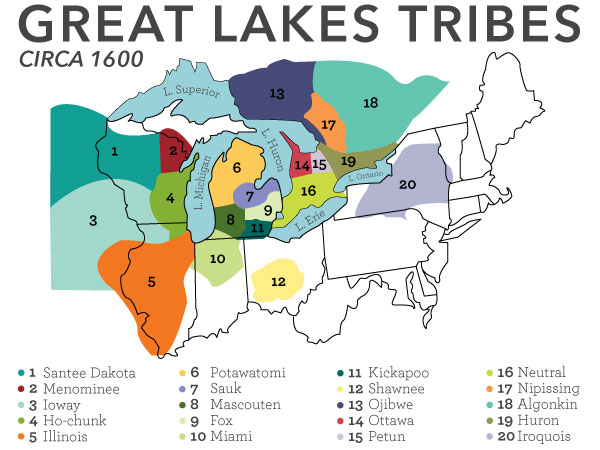

The vast expanse of the Great Lakes, a freshwater sea at the heart of North America, has for millennia been the homeland of diverse Indigenous nations. Far from mere geographical features, these waters and the surrounding lands are deeply interwoven with a rich tapestry of cultural teachings, philosophies, and practices that continue to shape the identities and worldviews of the Anishinaabeg (Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi), Haudenosaunee (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, Tuscarora), and many other Original Peoples. These teachings, often passed down through oral traditions, ceremonies, and lived experience, offer profound insights into interconnectedness, responsibility, and sustainable living – wisdom that holds immense relevance for contemporary global challenges.

At the core of Great Lakes Indigenous teachings lies the principle of Mino-Bimaadiziwin, or "The Good Life" – a holistic concept emphasizing balance, harmony, and well-being not just for oneself, but for family, community, and all of creation. This is not merely an individual pursuit but a communal responsibility, underpinned by a deep understanding of kinship with the natural world. "We are all related," is a common refrain, encapsulating the belief that humans are not separate from, but an integral part of, the intricate web of life. Every tree, every animal, every drop of water, and every rock possesses spirit and deserves respect. This worldview contrasts sharply with anthropocentric perspectives that often dominate Western thought, offering instead a model of co-existence and mutual reliance.

One of the most foundational tenets is the concept of stewardship and responsibility to future generations. The Haudenosaunee principle of considering the Seventh Generation in every decision exemplifies this foresight. Before undertaking any significant action, leaders are urged to reflect on its potential impact seven generations into the future, ensuring that choices made today do not compromise the well-being of those yet to come. This long-term vision has profoundly shaped traditional land management practices, promoting sustainable harvesting, conservation, and respectful interaction with the environment. For instance, the Anishinaabeg practice of harvesting manoomin (wild rice) involves careful, non-destructive methods that ensure the plant’s continued growth, demonstrating a reciprocal relationship rather than mere extraction.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is another cornerstone of these teachings. Generations of observation, experimentation, and spiritual connection have endowed Great Lakes Indigenous communities with an unparalleled understanding of their local ecosystems. Elders hold vast knowledge of plant medicines, animal behaviors, weather patterns, and the intricate balance of the land and water. This knowledge, often dismissed or overlooked by colonial systems, is now increasingly recognized by Western science as vital for addressing biodiversity loss and climate change. As one Ojibwe Elder remarked, "The land is our first teacher. It holds the stories, the medicines, and the lessons we need to live." This profound relationship with the land is not abstract; it is lived daily through hunting, fishing, gathering, and ceremonial practices that reinforce the sacred bond.

Language serves as the vessel for much of this wisdom. Indigenous languages like Ojibwemowin, Potawatomi, and Oneida are not just communication tools; they embody unique worldviews, philosophical constructs, and cultural nuances that are difficult, if not impossible, to translate directly. For example, many Indigenous languages are verb-based, emphasizing processes and relationships rather than static nouns, reflecting a dynamic and interconnected understanding of reality. The words themselves carry teachings, histories, and spiritual significance. The ongoing efforts to revitalize these languages are therefore critical to preserving and transmitting the full depth of cultural teachings. Language immersion schools and community programs are working tirelessly to ensure these vital tongues continue to speak.

Storytelling (Dibaajimowinan) is the primary pedagogical method through which cultural teachings are passed down. From creation stories and origin myths to cautionary tales and trickster narratives involving figures like Nanabush, these stories convey moral lessons, historical knowledge, spiritual insights, and practical survival skills. They are not mere entertainment but living textbooks, fostering critical thinking, empathy, and a deep connection to ancestral wisdom. Through the metaphor and symbolism embedded in these narratives, children and adults alike learn about the sacredness of life, the consequences of imbalance, and the importance of community harmony.

Ceremonies and rituals are active expressions of these teachings, providing pathways for spiritual connection, healing, and community bonding. The sweat lodge (Madoodiswan), for example, is a powerful ceremony of purification and prayer, connecting participants to the earth, water, fire, and air. Pipe ceremonies offer gratitude and foster unity. Seasonal ceremonies, such as maple sugar camps or harvest feasts, reinforce gratitude for the gifts of the land and mark the cyclical nature of life. These practices are not relics of the past but living traditions, continuously adapting while maintaining their core spiritual integrity, offering a profound sense of identity and belonging.

The clan system, particularly prominent among the Anishinaabeg, also reinforces cultural teachings. Each clan (e.g., Bear, Marten, Loon, Fish) is associated with specific responsibilities, gifts, and roles within the community, promoting a collective social structure where every member contributes to the well-being of the whole. For instance, the Bear Clan often holds responsibilities related to healing and medicine, while the Loon Clan might be associated with leadership and governance. This system fosters interdependence, respect for diversity, and a strong sense of collective identity, reminding individuals of their place and purpose within the broader community.

In the face of relentless colonial pressures – including forced assimilation, residential schools, and the suppression of language and culture – Great Lakes Indigenous Peoples have demonstrated remarkable resilience. Today, there is a powerful resurgence of cultural revitalization efforts. Communities are reclaiming their languages, restoring traditional practices, and reasserting their sovereignty and stewardship over ancestral lands and waters. Elders, who endured immense hardship to preserve their knowledge, are now actively mentoring younger generations, ensuring the continuity of these vital teachings. Cultural camps, youth mentorship programs, and Indigenous-led environmental initiatives are blossoming across the region, demonstrating the enduring strength and adaptability of these traditions.

The Great Lakes Original Peoples’ cultural teachings offer invaluable lessons for all humanity. Their emphasis on interconnectedness, long-term stewardship, and reciprocal relationships with the natural world provides a potent antidote to the ecological crises and social fragmentation of our time. They remind us that true prosperity is not measured in material wealth, but in the health of our relationships – with each other, with the land, and with the spiritual forces that animate all life. As we navigate an increasingly complex world, the profound wisdom emanating from the heart of the Great Lakes stands as a beacon, guiding us towards a more balanced, respectful, and sustainable future.