A Fragile Promise, a Lasting Betrayal: The Enduring Legacy of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty

On a crisp November day in 1868, under the vast, indifferent sky of what is now Wyoming, a landmark agreement was sealed at Fort Laramie. For the United States government, it was a strategic capitulation, a rare admission of defeat in the face of indigenous resistance. For the Lakota, Dakota, and Arapaho peoples, it was a moment of hard-won triumph, a testament to their strength and the fierce determination of leaders like Red Cloud. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, signed by various bands of Sioux, including the Oglala and Brulé, as well as the Arapaho, ostensibly promised perpetual peace, vast tracts of protected land, and a future free from the encroaching tide of American expansion. Yet, this pivotal document, intended to be "as long as the grass grows and the rivers flow," would instead become a tragic testament to broken promises, a blueprint for future conflict, and a enduring symbol of the profound injustices woven into the fabric of American history.

To understand the treaty’s immense significance, one must first grasp the tumultuous landscape from which it emerged. The mid-19th century was an era of fervent Manifest Destiny, a belief that divine providence ordained American expansion across the continent. This ideology fueled relentless westward migration, driven by the California Gold Rush, the promise of fertile lands, and the construction of transcontinental railroads. The Great Plains, the ancestral home of powerful nomadic tribes like the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, lay directly in the path of this expansion. Their traditional way of life, centered around the buffalo and their sacred lands, was increasingly threatened by settlers, miners, and soldiers.

The immediate catalyst for the 1868 treaty was Red Cloud’s War (1866-1868), a conflict born from the construction of the Bozeman Trail. This trail, blazed by John Bozeman, offered a shorter route to the Montana goldfields, cutting directly through the heart of the Lakota’s prime buffalo hunting grounds in the Powder River Country. The U.S. government, despite previous treaty agreements, proceeded to establish forts along the trail – Fort Reno, Fort C.F. Smith, and Fort Phil Kearny – effectively militarizing Lakota territory. This aggressive act ignited the fury of the Oglala Lakota chief, Red Cloud (Makhpiya Lúta), who famously declared, "The Great Spirit made us to live as we do. He gave us the buffalo for food and clothing, and the ground to live upon. He meant that we should be free."

Red Cloud, a brilliant strategist and an unwavering defender of his people’s lands, launched a highly effective guerrilla campaign. His warriors harassed supply trains, isolated garrisons, and ambushed patrols. The Fetterman Fight in December 1866, where a detachment of 81 U.S. soldiers and civilians under Captain William J. Fetterman were annihilated by Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors, was a devastating blow to American morale and military prestige. It underscored the U.S. Army’s inability to secure the Bozeman Trail and subdue the formidable coalition of tribes. The cost in lives and resources became unsustainable, forcing the U.S. government to the negotiating table. This was a rare instance where the United States conceded defeat in a military conflict against Native Americans.

The Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868 was thus a product of necessity for the United States. Its primary provisions were monumental:

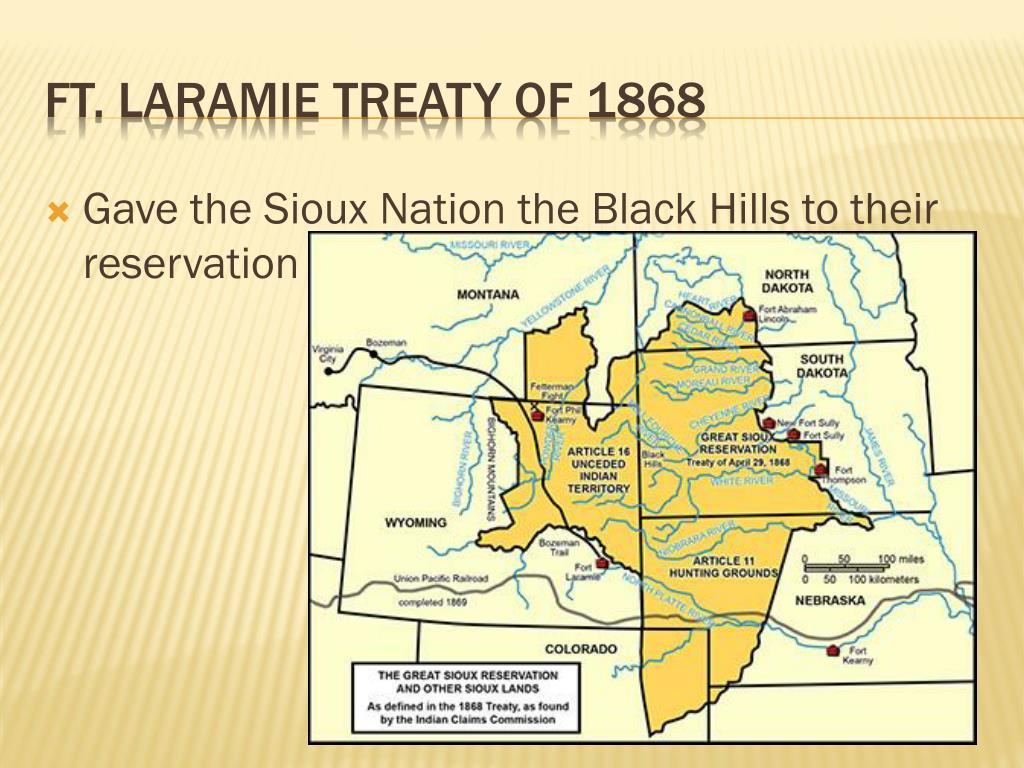

- The Great Sioux Reservation: The treaty established a vast reservation for the "absolute and undisturbed use and occupation of the Sioux Indians," encompassing all of present-day South Dakota west of the Missouri River, including the sacred Black Hills (Paha Sapa). This land was set aside "for the exclusive use and occupation of the said Indians," and no white person was permitted to settle or even pass through it without tribal consent.

- Unceded Territory: An even larger area, stretching into parts of Nebraska, Wyoming, and Montana, was designated as "unceded Indian territory," recognized as traditional hunting grounds where the tribes could continue their nomadic way of life, free from white intrusion.

- Abandonment of Forts: Crucially, the U.S. government agreed to abandon and dismantle its forts along the Bozeman Trail – a key demand of Red Cloud, who refused to sign the treaty until the last soldier had departed and the forts were burned. This unprecedented concession marked a clear victory for Native American military power.

- Assimilation Provisions: The treaty also included clauses reflecting the U.S. government’s assimilationist policies. It offered incentives for tribesmen to adopt farming, promised schools, and provided annuities (goods and supplies) in exchange for peace and adherence to the treaty. These provisions were designed to transform nomadic hunters into sedentary farmers, a strategy aimed at dismantling tribal culture and facilitating further land acquisition.

The immediate aftermath of the treaty brought a fragile peace. Red Cloud, having achieved his primary objective, signed the treaty in November 1868, several months after most other chiefs, only when he was assured the forts were indeed abandoned. His insistence on this point highlighted his astute understanding of power dynamics and his unwavering commitment to his people’s sovereignty. For a brief period, the Lakota and their allies enjoyed a respite from the relentless pressure of westward expansion, holding sway over a territory larger than many European nations.

However, the ink on the treaty was barely dry before its promises began to unravel. The U.S. government’s commitment to "perpetual peace" and the inviolability of the Great Sioux Reservation proved to be ephemeral, subordinate to the insatiable hunger for land and resources. The most egregious violation centered on the Black Hills. For the Lakota, Paha Sapa was the sacred heart of their world, the place where the Creator had placed them, a spiritual sanctuary essential to their identity and ceremonies. The 1868 treaty explicitly protected it.

Yet, rumors of gold in the Black Hills persisted. In 1874, defying the treaty, the U.S. government dispatched a military expedition led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer to survey the region. Custer’s confirmation of "gold from the grass roots down" triggered a massive gold rush. Thousands of miners, prospectors, and settlers poured into the Black Hills, brazenly violating the treaty. The U.S. government, instead of expelling the trespassers as obligated, demanded that the Lakota sell the Black Hills. When the Lakota, under leaders like Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, refused to part with their sacred lands, the government issued an ultimatum: return to the agencies by January 31, 1876, or be deemed "hostile." This manufactured crisis directly led to the Great Sioux War of 1876, culminating in the Battle of Little Bighorn, where Custer and his command were famously annihilated.

Despite this stunning Native American victory, the superior military and industrial might of the United States ultimately prevailed. By 1877, the Lakota were defeated, their leaders killed or imprisoned, and their traditional way of life shattered. Congress unilaterally passed an act seizing the Black Hills, reducing the Great Sioux Reservation by millions of acres. This act, a blatant violation of the 1868 treaty, which required the signatures of three-fourths of all adult male Lakota to cede land, marked the definitive betrayal of the Fort Laramie promise.

The legacy of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty extends far beyond the 19th century, reverberating through contemporary legal battles and the ongoing struggle for Native American rights. In 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court, in United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians, ruled that the government had indeed illegally abrogated the 1868 treaty and seized the Black Hills. Justice Harry Blackmun, in the majority opinion, wrote that "a more ripe and rank case of dishonorable dealings will never, in all probability, be found in our history." The Court awarded the Sioux Nation $17.1 million for the fair market value of the land at the time of its taking, plus 5% simple interest per year since 1877, totaling over $100 million.

However, the Sioux Nation has steadfastly refused to accept the monetary settlement, which has now grown to over $1 billion. For them, the Black Hills are not for sale; they are sacred. Their demand remains the return of the land, not compensation for its theft. This principled refusal underscores the deep spiritual and cultural connection to the land that transcends monetary value, and highlights the ongoing profound disconnect between Native American perspectives and those of the U.S. government.

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 stands as a powerful, if painful, historical artifact. It represents a rare moment of Native American military success and diplomatic leverage, forcing the most powerful nation on earth to retreat. Yet, it simultaneously serves as a stark reminder of the U.S. government’s habitual disregard for its treaty obligations, its willingness to break solemn agreements when resources or expansionist desires dictated. It symbolizes the systematic dispossession of indigenous peoples, the destruction of their cultures, and the enduring scars of colonialism.

In the 21st century, the treaty’s significance endures as a cornerstone of Native American legal and political claims for sovereignty, self-determination, and land rights. It is a document that continues to be invoked in discussions about environmental protection, cultural preservation, and the pursuit of justice for historical wrongs. The broken promises of Fort Laramie are not mere historical footnotes; they are living wounds that continue to shape the identities, struggles, and aspirations of the Lakota and other indigenous nations, serving as a powerful and tragic testament to a promise made, then shattered, forever impacting the soul of a nation and its first peoples.