The Unflinching Gaze: Reclaiming Thanksgiving from an Indigenous Perspective

The story of the First Thanksgiving, as etched into the American consciousness, is a comforting tableau: Pilgrims and Native Americans, sharing a bountiful harvest in harmonious gratitude. It’s a narrative of unity, cooperation, and the birth of a nation rooted in shared bounty. Yet, for the Indigenous peoples of North America, particularly the Wampanoag Nation upon whose ancestral lands this event transpired, the historical truth is far more complex, poignant, and ultimately, a precursor to centuries of displacement, disease, and violence. To truly understand the "First Thanksgiving" requires an unflinching gaze at history from the perspective of those who, for too long, have been relegated to the periphery of their own story.

The traditional Thanksgiving narrative, taught in schools and celebrated in homes, often begins with the arrival of the Mayflower in 1620. It speaks of the Pilgrims’ struggles, their survival aided by "friendly natives," and a shared feast in 1621. This simplified version, however, omits critical context, ignores the pre-existing vibrant Indigenous societies, and glosses over the devastating forces already at play long before the Mayflower dropped anchor.

Before the Pilgrims’ arrival, the Wampanoag Confederacy was a powerful and sophisticated network of communities inhabiting what is now southeastern Massachusetts and eastern Rhode Island. For thousands of years, they had cultivated the land, developed complex governance structures, and sustained themselves through agriculture, hunting, and fishing. Their world was rich, interconnected, and thriving.

However, this world had already been catastrophically disrupted. Beginning in 1616, just four years before the Mayflower, a series of European-borne epidemics – likely leptospirosis or bubonic plague – swept through the coastal Indigenous communities. These diseases, against which Native peoples had no immunity, decimated the Wampanoag population, killing an estimated 75-90% of their people. Entire villages were wiped out, leaving behind ghost towns and a profoundly weakened society. This "Great Dying" is a crucial, yet often overlooked, prelude to the Pilgrim narrative. It was into this ravaged landscape that the Pilgrims stumbled, finding fertile fields recently cleared by those who had perished, and a people reeling from an unprecedented demographic catastrophe.

When the English Separatists landed at Patuxet (which they renamed Plymouth), they were trespassers on Wampanoag land. Their survival during that brutal first winter was tenuous, marked by starvation and disease. Their fortunes began to change with the appearance of two key Wampanoag figures: Samoset, an Abenaki man who had learned some English from fishermen, and Tisquantum, better known as Squanto. Tisquantum’s story is a tragic microcosm of early colonial encounters. He had been kidnapped by English explorer Thomas Hunt in 1614, enslaved in Spain, and eventually made his way back to his homeland only to find his entire village of Patuxet annihilated by the plague. He was a man caught between two worlds, invaluable to the Pilgrims as an interpreter and mediator, but also a survivor navigating immense personal loss and political upheaval.

It was Tisquantum who facilitated the pivotal meeting between the Pilgrims and Ousamequin, the Massasoit (great leader) of the Wampanoag Confederacy. The alliance forged in March 1621 was not born of inherent friendship or mutual affection, but of strategic necessity for the Wampanoag. Ousamequin, with his people severely weakened by disease and facing threats from rival tribes like the Narragansett, saw an opportunity in the English. A mutual defense treaty with the armed newcomers could provide a much-needed strategic advantage. For the Pilgrims, the alliance was about survival, securing peace, and gaining access to vital knowledge for farming and foraging.

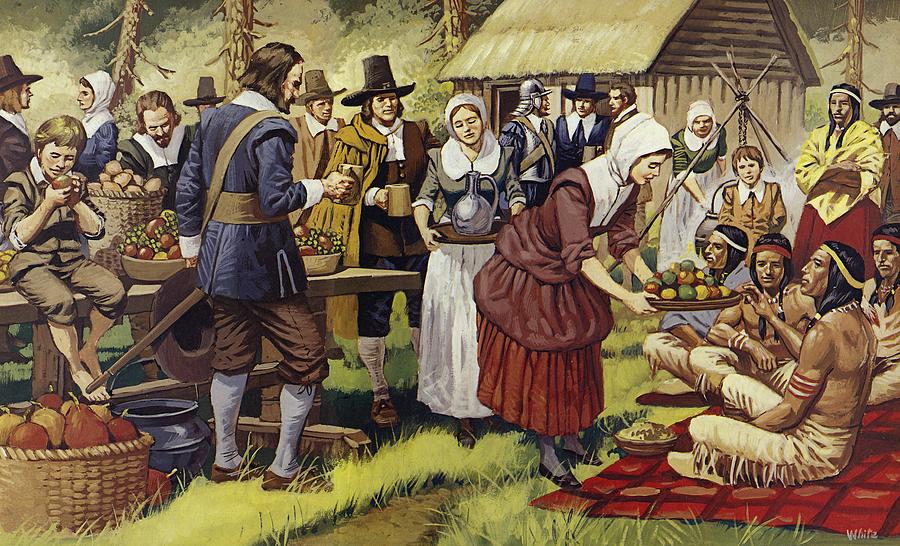

The "First Thanksgiving" in 1621, as recorded by Pilgrim chronicler Edward Winslow, was a three-day harvest festival. Winslow’s brief account mentions that Governor William Bradford sent four men fowling, and that "many of the Indians" came, including Massasoit, who brought "some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the Plantation and bestowed on the Governor, and upon the Captain and others."

This passage reveals several crucial details often omitted from popular retellings. Firstly, the Wampanoag were not "invited" in the modern sense; they arrived after hearing the Pilgrims’ celebratory gunfire, likely concerned about potential conflict. Secondly, the Wampanoag contingent, numbering around 90 men, far outnumbered the roughly 50 surviving Pilgrims. Thirdly, the Wampanoag contributed significantly to the feast, providing five deer, suggesting they were not merely guests but active participants in a diplomatic gathering. This was less a spontaneous, friendly dinner and more a formal affirmation of their recent alliance, with both sides demonstrating their strength and capabilities. It was a political event, a strategic gathering, rather than a purely grateful celebration.

Crucially, the Wampanoag already had a tradition of giving thanks, a practice deeply embedded in their spirituality and daily life, expressed through ceremonies for various harvests, hunts, and blessings throughout the year. The English concept of "Thanksgiving" was alien to them; their presence was about the current political climate, not a shared cultural holiday.

This fragile alliance, however, would prove to be a fleeting interlude before decades of escalating tensions erupted into the brutal conflict known as King Philip’s War (1675-1678). As more English settlers arrived, their demand for land grew insatiable. Treaties were broken, Wampanoag sovereignty was systematically undermined, and their traditional ways of life were threatened by the encroaching colonial society, its laws, and its religion.

Ousamequin’s son, Metacom (known to the English as King Philip), inherited a world where his people were increasingly marginalized and oppressed. He recognized the existential threat posed by colonial expansion and, in a desperate attempt to preserve Wampanoag independence and culture, led a confederation of Native tribes in a devastating war against the English. King Philip’s War was one of the bloodiest conflicts in American history, proportionally, resulting in thousands of deaths on both sides. For the Wampanoag and their allies, it was catastrophic. Their resistance was ultimately crushed, Metacom was killed, and many surviving Wampanoag were enslaved or fled their ancestral lands. The war effectively ended Indigenous sovereignty in southern New England, paving the way for unchecked colonial expansion.

The traditional Thanksgiving narrative, therefore, serves to whitewash this violent history, transforming a complex political interaction into a benign myth of national unity. It erases the Wampanoag’s pre-colonial existence, their suffering, their strategic agency, and the subsequent genocide and land dispossession that followed.

For many Indigenous peoples today, Thanksgiving is not a day of celebration but a National Day of Mourning. This counter-commemoration, initiated in 1970 by the United American Indians of New England (UAINE) and held annually on Cole’s Hill in Plymouth, Massachusetts, serves as a powerful reminder of the true cost of colonization. "For Native people, Thanksgiving is a day of mourning, not celebration," states Mahtowin Munro, co-leader of UAINE. "It marks the beginning of Native genocide, the theft of Native lands, and the relentless assault on Native culture."

The act of reclaiming the Thanksgiving narrative is not about condemning gratitude or rejecting the idea of coming together. It is about demanding historical accuracy, acknowledging the full spectrum of human experience, and understanding the profound impact of colonial history on Indigenous communities, impacts that continue to resonate today. It calls for a deeper reflection on what we choose to celebrate and how we choose to remember.

To truly honor history, we must move beyond the sanitized myths and engage with the uncomfortable truths. Recognizing the Indigenous perspective of the First Thanksgiving means understanding the immense resilience of the Wampanoag people, the strategic brilliance of Massasoit, the tragic saga of Tisquantum, and the devastating consequences of unchecked colonialism. It means acknowledging that the "First Thanksgiving" was a moment in a much larger, often brutal, historical trajectory. Only by facing these truths can we begin to foster genuine understanding, respect, and ultimately, a more just and equitable future.