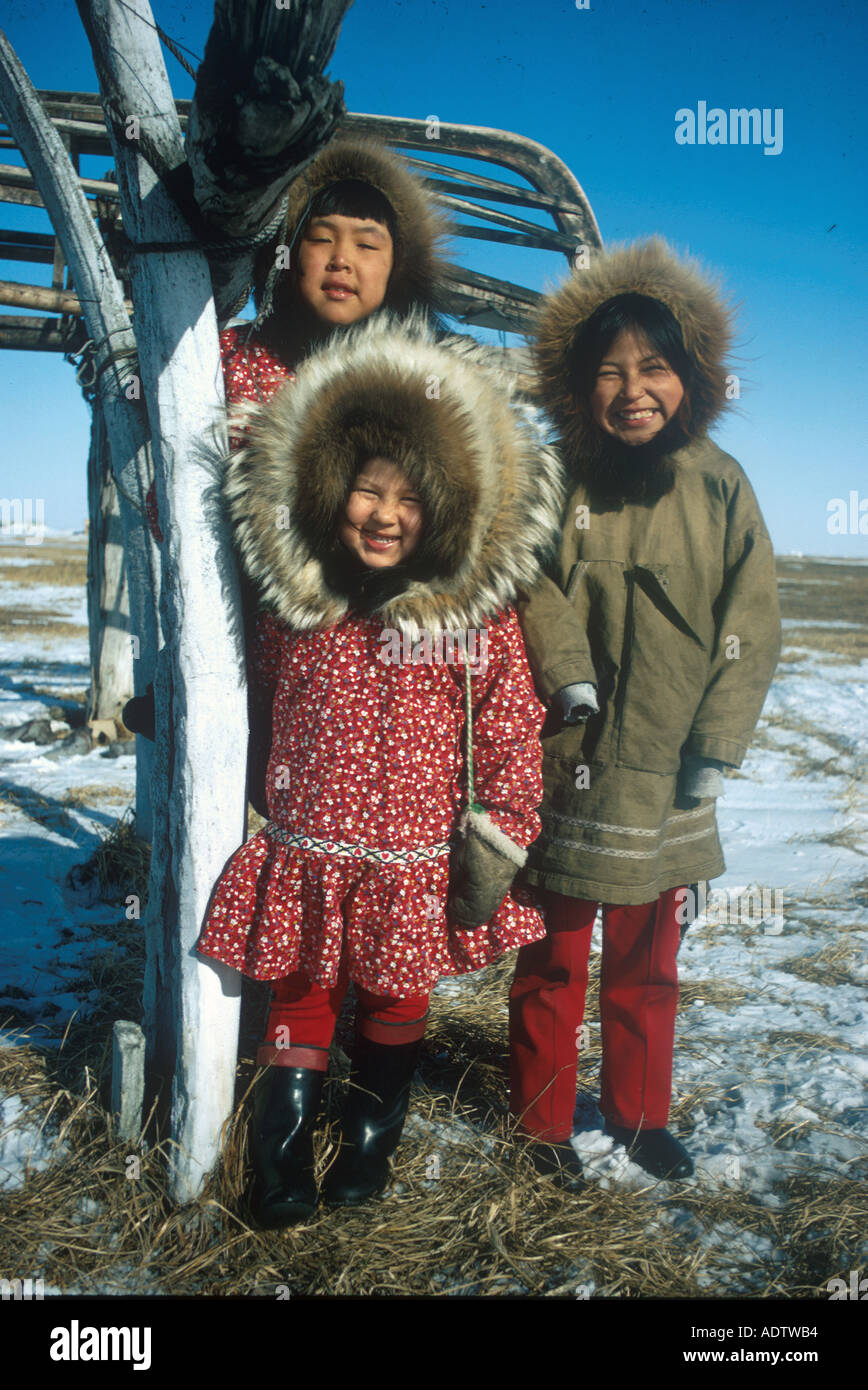

In the vast, unforgiving landscapes of the Arctic, where temperatures plummet and survival hinges on ingenuity, the clothing worn by Indigenous peoples, often referred to as Eskimos, is nothing short of a marvel. This is especially true for children, whose vulnerability to extreme cold necessitates garments of exceptional warmth, durability, and practicality.

The term ‘Eskimo’ is a broad exonym often used to refer to the Indigenous peoples of the Arctic, including the Inuit and Yupik. While the term ‘Inuit’ is preferred by many, the clothing traditions across these groups share common principles rooted in millennia of adaptation to the world’s most extreme cold environments.

For children growing up in these conditions, clothing is not merely a covering; it is a meticulously crafted second skin, designed to offer unparalleled protection against blizzards, freezing winds, and sub-zero temperatures. Understanding these garments provides a window into a rich cultural heritage and a testament to human resilience.

Historically, the primary goal of Arctic clothing was simple: survival. Every stitch, every material choice, and every design element served a crucial purpose in insulating the wearer and preventing hypothermia. For children, this was paramount, as their smaller bodies lose heat more rapidly.

Traditional Eskimo children’s clothing evolved over thousands of years, perfected through generations of trial and error. The materials were sourced directly from their environment, primarily animals that thrived in the Arctic, providing both sustenance and essential resources for clothing.

The ingenuity lay in understanding the insulating properties of different furs and hides, and how to combine them to create multi-layered systems that trapped air, allowing body heat to be retained effectively. This knowledge was passed down from elder to child, often through direct apprenticeship.

One of the most iconic pieces of traditional Inuit clothing, particularly for mothers and infants, is the Amauti. This distinctive parka features a large pouch on the back, allowing a mother to carry her baby warmly and securely against her body, sharing warmth and facilitating easy breastfeeding.

The Amauti is a prime example of how traditional clothing serves multiple functions: protection from the elements, infant care, and a strong cultural identifier. For young children, smaller versions of these parkas would be crafted, ensuring they too benefited from superior insulation.

Beyond parkas, children’s attire included specialized pants, often made from caribou hide, designed to be loose-fitting to allow for layering and movement. These would be tucked into boots, creating a continuous barrier against the cold.

Footwear, known as Kamiks (or mukluks in some regions), was equally critical. Traditionally crafted from seal skin or caribou hide, Kamiks were designed to be waterproof and incredibly warm. They often featured inner liners of fur or grass for added insulation and moisture wicking.

The craftsmanship involved in creating Kamiks was highly skilled, requiring precise cutting and sewing to ensure a snug yet comfortable fit that prevented frostbite. Children’s Kamiks were made with the same attention to detail as adult versions, often with reinforced soles for durability during play.

Mittens, typically made from fur-lined hide, were essential for protecting small hands. Unlike gloves, mittens keep fingers together, maximizing warmth. They were often attached to a string or cord, threaded through the parka sleeves, to prevent them from getting lost during active play.

The primary materials for traditional Arctic clothing were animal hides and furs. Caribou skin was highly valued for its exceptional insulating properties, thanks to its hollow hairs that trap air. Seal skin provided excellent waterproofing and durability, especially for boots and outer layers.

Other furs, such as polar bear, wolf, or fox, were also utilized for trim, hoods, and inner linings, adding extra warmth and protection. The choice of material often depended on local availability and the specific function of the garment.

The preparation of these materials was an arduous process, involving scraping, stretching, and tanning the hides. This labor-intensive work, traditionally performed by women, was crucial for creating pliable, durable, and weather-resistant garments.

Beyond functionality, traditional Eskimo clothing often incorporated intricate designs, embroidery, and decorative elements. These patterns were not merely aesthetic; they often carried cultural meanings, indicating tribal affiliation, status, or personal stories. Even children’s clothing reflected this artistry.

In contemporary times, while traditional clothing remains vital for cultural preservation and practical use in many communities, modern synthetics and materials have also been integrated. This fusion allows for enhanced performance in some aspects, while still honoring traditional designs and methods.

Today, you can find children’s cold-weather gear inspired by Inuit designs, particularly in the use of insulated parkas with fur-trimmed hoods. These modern adaptations pay homage to the effectiveness of traditional Arctic wear in protecting against extreme cold.

For those interested in acquiring authentic or inspired pieces, it’s important to seek out products made by Indigenous artisans or companies that ethically source materials and support Arctic communities. This ensures that the cultural heritage and craftsmanship are respected and sustained.

Caring for traditional clothing, especially those made from natural hides and furs, requires specific knowledge. Proper drying, storage, and occasional treatment are essential to maintain their insulating properties and longevity. These practices are often part of the cultural knowledge passed down through families.

The legacy of Eskimo children’s clothing is a powerful testament to human adaptation and cultural richness. It underscores the deep connection between people and their environment, where every element of design and material choice reflects a profound understanding of nature’s challenges.

From the ingenious Amauti that keeps babies close and warm, to the robust Kamiks that brave icy terrains, these garments represent more than just protection from the cold; they embody identity, heritage, and the enduring spirit of Arctic communities.

- Ingenious Adaptation: Garments meticulously designed for extreme cold.

- Natural Materials: Reliance on caribou, seal, and other furs for superior insulation.

- Cultural Significance: Clothing as a carrier of identity, tradition, and intergenerational knowledge.

- Enduring Legacy: Influence on modern winter wear and continued importance in Arctic communities.

Understanding these traditions helps us appreciate the remarkable resilience and creativity of Indigenous peoples in the Arctic, whose innovations continue to inspire and inform our approach to cold-weather protection.