Guardians of the Green: The Desperate Fight for Endangered Turtles on Turtle Island

On the azure canvas of the Sulu Sea, a cluster of emerald gems emerges, bearing a name that speaks volumes about their ecological significance: the Turtle Islands. This remote archipelago, straddling the maritime borders of Malaysia and the Philippines, is not merely a picturesque tropical paradise. It is one of the last bastions for some of the planet’s most ancient mariners – the endangered green and hawksbill sea turtles – and a critical battleground in the escalating war against extinction. Here, on these hallowed nesting grounds, a fragile ecosystem struggles for survival against a tide of human-induced threats, making every dawn a testament to resilience and every sunset a reminder of the urgent work that remains.

The Turtle Islands Heritage Protected Area (TIHPA), established in 1996, represents a unique bi-national conservation effort, encompassing nine islands where female turtles have journeyed for millennia to lay their eggs. Six of these islands fall under Philippine jurisdiction, while the remaining three – Selingan, Bakungan Kecil, and Gulisan – belong to Malaysia, collectively forming Sabah’s Turtle Islands Park. This cross-border cooperation underscores the transboundary nature of marine conservation, as these magnificent creatures know no political boundaries in their vast oceanic migrations.

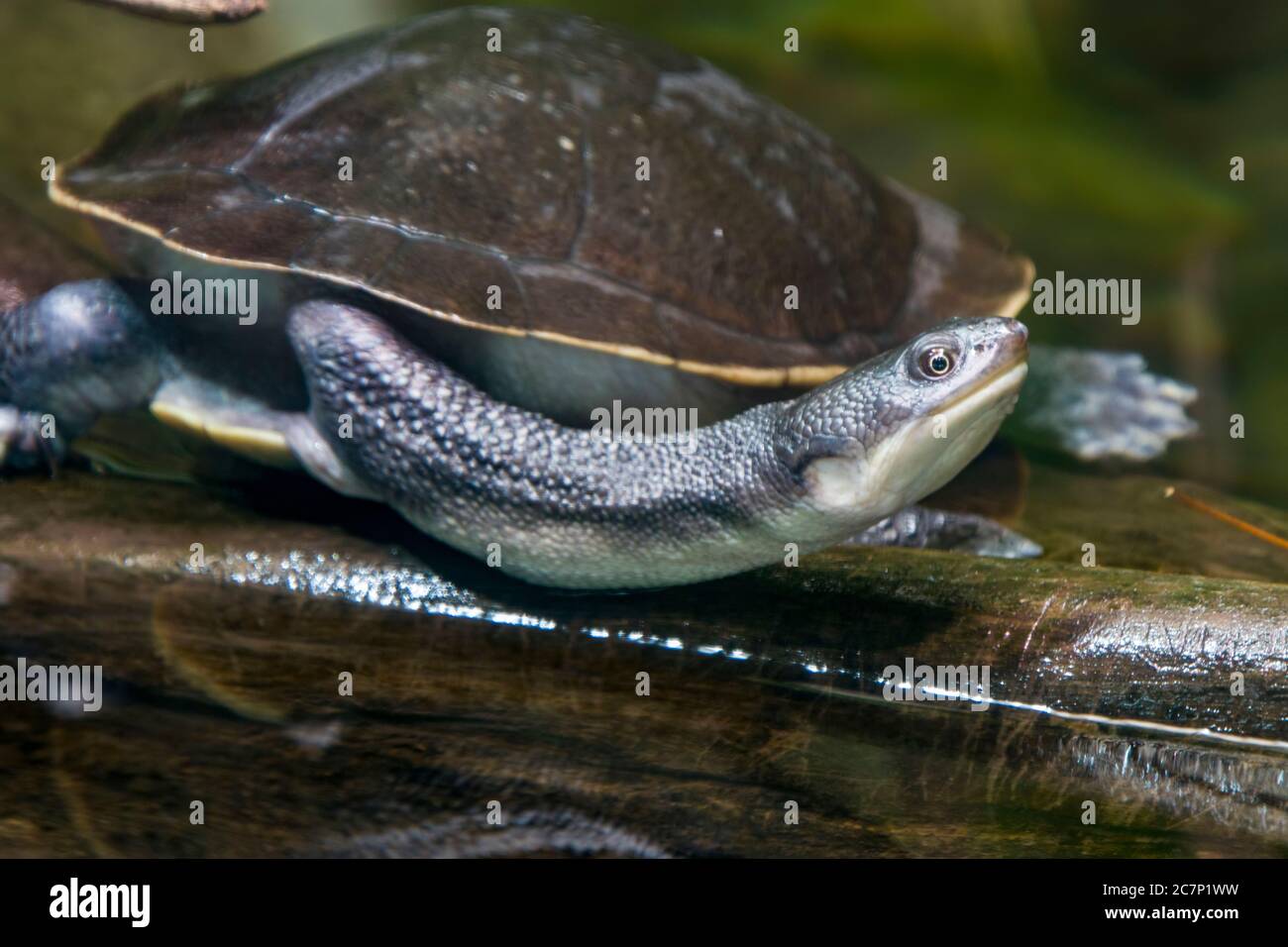

For the green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas), Turtle Island is an ancestral home. Known for their distinct olive-green carapace and herbivorous diet, green turtles are the largest of the hard-shelled sea turtles, capable of growing up to five feet long and weighing over 700 pounds. Their journey to these islands is an epic feat of navigation, often spanning thousands of kilometres across open ocean. Each nesting season, under the cloak of night, the females emerge from the waves, hauling their massive bodies across the sand to painstakingly excavate a nest where they will deposit hundreds of soft, leathery eggs. It is a ritual as old as time, a primal act of perpetuation against incredible odds.

Equally imperilled is the hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), named for its distinctive narrow, pointed beak. Smaller and more agile than the green turtle, hawksbills are crucial inhabitants of coral reefs, where their diet of sponges helps maintain the health and biodiversity of these vital underwater ecosystems. Their beautifully patterned shells, unfortunately, have also been their curse. The "bekko" trade, which uses their scutes for decorative items like jewellery and ornaments, has decimated their populations for centuries, pushing them to the brink of commercial extinction. On Turtle Island, their presence, though less numerous than greens, is a poignant reminder of the precious biodiversity at stake.

The life cycle of a sea turtle is a harrowing tale of survival against overwhelming odds. From the moment the eggs are laid, they face threats from natural predators like monitor lizards and birds. Once hatched, typically after 45-75 days, the tiny hatchlings undertake a perilous dash across the sand, guided by the moonlight reflecting off the ocean, to reach the relative safety of the sea. It’s a journey fraught with danger, where crabs, birds, and even artificial lights can disorient them. Only an estimated 1 in 1,000 to 10,000 hatchlings will survive to adulthood, a statistic that underscores the critical importance of protecting every single nest.

Yet, the ancient rhythms of life on Turtle Island are increasingly disrupted by a barrage of modern threats. Climate change looms as perhaps the most insidious danger. Rising sea levels threaten to inundate low-lying nesting beaches, eroding the very land where turtles have nested for millennia. More alarmingly, the temperature of the sand where eggs incubate determines the sex of the hatchlings – a phenomenon known as Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination (TDSD). Warmer sands produce more females, while cooler sands yield more males. With global temperatures steadily climbing, scientists fear a dramatic skewing of sex ratios, leading to a severe lack of males and jeopardizing the reproductive viability of future generations.

"A mere 1-2 degrees Celsius increase in sand temperature can skew the sex ratio dramatically towards females, potentially leading to a ‘feminization’ of the population," explains Dr. Anya Sharma, a marine biologist with the World Wildlife Fund, who has spent years studying the region. "If we lose too many males, the genetic diversity of the population will plummet, making them even more vulnerable to other environmental stressors and diseases. It’s a ticking time bomb for these ancient species."

Beyond climate change, the ubiquitous scourge of plastic pollution chokes the life out of the ocean. Ghost fishing nets, discarded by commercial fishing vessels, drift for years, entangling and drowning countless turtles. Microplastics, ingested by turtles, can cause internal injuries, block digestive tracts, and leach toxins into their systems. Turtle Island, despite its remote location, is not immune to this global crisis, with marine debris regularly washing ashore on its pristine beaches.

Direct human exploitation remains a significant threat. Despite stringent laws, poaching of turtle eggs for consumption and adult turtles for meat and shells persists, driven by local demand and the lucrative illegal wildlife trade. The Hawksbill’s beautiful shell, once highly prized for "bekko" products, still fuels a black market, particularly in Southeast Asia. Furthermore, destructive fishing practices, such as trawling and longlining, result in countless turtles becoming bycatch – unintentionally caught and often killed. Coastal development, light pollution from nearby settlements, and increased boat traffic also disturb nesting sites and migratory routes, adding layers of pressure on an already struggling population.

In response to these dire threats, the conservation efforts on Turtle Island are both intensive and inspiring. The park rangers and conservationists are the frontline guardians, working tirelessly to monitor nesting activities, relocate vulnerable nests to protected hatcheries, and release hatchlings safely into the sea. Each night, patrols scour the beaches for nesting females, meticulously recording data, measuring the turtles, and tagging them for future identification and research.

"It’s a demanding job, often under challenging conditions, but the sight of hundreds of hatchlings scurrying towards the ocean makes every sacrifice worthwhile," says Pak Cik Rahman, a veteran ranger on Selingan Island, his face weathered by years under the sun. "We are not just protecting turtles; we are protecting a piece of our heritage, a symbol of our ocean’s health. Our grandfathers saw these turtles; we want our grandchildren to see them too."

The TIHPA also serves as a living laboratory for scientific research. Satellite tagging programs track the epic migrations of adult turtles, providing invaluable data on their feeding grounds, migration corridors, and potential threats encountered along their journey. This information is crucial for establishing wider marine protected areas and influencing policy decisions that can safeguard these species across their entire range. Genetic studies help assess population health and diversity, guiding captive breeding and conservation strategies.

Ecotourism, carefully managed, plays a dual role. It provides much-needed funding for conservation efforts and raises public awareness about the plight of sea turtles. Visitors to Selingan Island, for instance, are allowed to witness the nesting process and the release of hatchlings under strict supervision, fostering a sense of wonder and responsibility. However, the delicate balance between human presence and wildlife protection is constantly evaluated to ensure minimal disturbance to the turtles.

The bi-national status of TIHPA is a testament to the power of international cooperation. Malaysia and the Philippines share not only these islands but also the responsibility for the future of these marine giants. Regular meetings, joint patrols, and shared research initiatives are vital in combating cross-border poaching and managing shared marine resources. This collaborative model offers a blueprint for conservation in other regions facing similar challenges.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/hawksbill-turtle-swimming-over-the-coral-reef--kimbe-bay--papua-new-guinea--1211306201-bec66cf88f964e648c921a3bfe7fdcd2.jpg)

The fight for the endangered turtles of Turtle Island is far from over. It is a complex, multi-faceted struggle against forces that are global in scale, from climate change to marine pollution and illegal wildlife trade. Yet, the dedicated efforts of rangers, scientists, local communities, and international partners offer a beacon of hope. Every protected nest, every successfully hatched turtle, every piece of plastic removed from the beach, and every person educated about their plight contributes to this colossal endeavour.

Turtle Island stands as a powerful symbol – a sanctuary, a battleground, and a promise. It reminds us that the fate of these ancient mariners is inextricably linked to our own. Their survival is a barometer of the health of our oceans, a bellwether for the ecological integrity of our planet. As the sun sets over the Sulu Sea, and the silhouette of a mother turtle slowly disappears back into the waves, the quiet determination of those who stand guard on Turtle Island echoes a universal truth: the fight to save these magnificent creatures is a fight to preserve a vital part of Earth’s natural legacy, a legacy we are all responsible for protecting for generations yet to come. The future of these living fossils, and indeed, the very soul of our blue planet, hangs in the balance, swaying gently with the tides of Turtle Island.