Guardians of Sovereignty: The Enduring Strategies of Early Native American Leaders

The narrative of early American history often casts Native American peoples as passive recipients of European expansion, or as fierce but ultimately outmatched adversaries. This perspective, however, profoundly underestimates the sophisticated and diverse leadership that guided Indigenous nations through centuries of unprecedented upheaval. From the first contact with European settlers to the nascent years of the American republic, early Native American leaders employed a remarkable array of strategies – diplomatic, military, spiritual, and economic – to safeguard their sovereignty, preserve their cultures, and protect their ancestral lands. Their stories are not merely footnotes in colonial history but testaments to profound resilience, adaptability, and an enduring vision for their peoples.

The challenges faced by these leaders were immense and multi-faceted. European arrival brought not only advanced weaponry and insatiable land hunger but also devastating diseases that decimated populations, disrupting social structures and weakening political cohesion. The introduction of new economies, particularly the fur trade, created dependencies and intensified inter-tribal rivalries. Navigating this treacherous landscape required leaders of extraordinary wisdom, courage, and foresight.

The Art of Diplomacy and Alliance Building: The Haudenosaunee Confederacy

Perhaps one of the earliest and most enduring examples of strategic genius predates extensive European contact: the formation of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, or the League of Peace and Power. Established centuries before Columbus, possibly around the 12th century, by the Great Peacemaker and Hiawatha, this union of initially five (later six) distinct nations (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora) was a groundbreaking achievement in diplomacy.

The Confederacy’s Great Law of Peace established a sophisticated democratic system, a federal structure with checks and balances, and a commitment to resolving internal disputes peacefully. This internal unity allowed the Haudenosaunee to project significant power externally, dominating the fur trade and often playing European powers against one another. Their strategic location and unified political voice made them a formidable force, dictating terms to both the French and the British for decades. The Haudenosaunee demonstrated that strength lay not just in military might, but in political cohesion and the ability to forge lasting alliances based on shared principles. Their influence on the framers of the U.S. Constitution has been noted by scholars, highlighting the profound impact of Indigenous governance models.

Powhatan: Calculated Engagement and Strategic Withdrawal

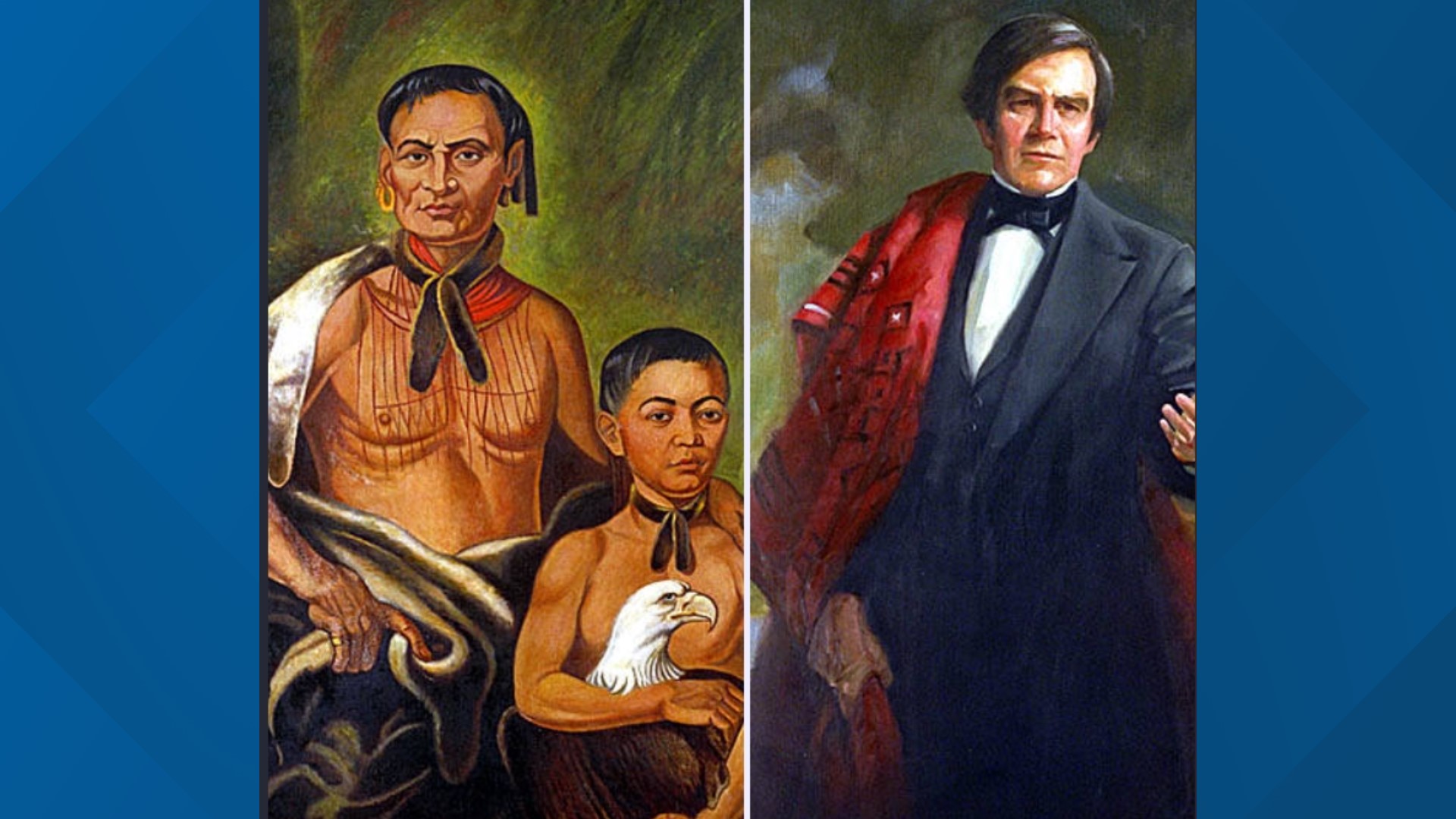

In the early 17th century, Chief Wahunsenacawh, better known as Powhatan, led a powerful confederacy of Algonquian-speaking tribes in what is now Virginia, just as the English established Jamestown. Powhatan faced the immediate challenge of an unfamiliar, land-hungry, and technologically superior intruder. His strategy was one of calculated engagement.

Initially, Powhatan sought to incorporate the English into his expansive network of tributary tribes, seeing them as a potential source of trade goods and military allies against his traditional enemies. He observed them, evaluated their strengths and weaknesses, and employed a mix of hospitality, intimidation, and strategic raids. His famous daughter, Pocahontas, played a role in these early diplomatic exchanges, her interactions with John Smith often serving as a bridge between two vastly different cultures.

However, as English intentions became clear—their insatiable demand for land and their refusal to be subjugated—Powhatan shifted tactics. He gradually withdrew his people from direct confrontation, relying on strategic ambushes and economic pressure (withholding food supplies) rather than open warfare, which he knew would be devastating. His understanding of the English reliance on his people’s resources was a key lever. Before his death in 1618, Powhatan reportedly warned his people against open war, recognizing the long-term threat. "Why should you destroy us who have provided you with food?" he once reportedly questioned the English, highlighting the economic interdependence he initially sought to leverage. His legacy is one of pragmatic leadership, attempting to manage an existential threat with a blend of diplomacy and strategic resistance.

Metacom (King Philip): Pan-Tribal Resistance and Desperate Measures

A generation later, in New England, the Wampanoag leader Metacom, known to the English as King Philip, faced a different reality. Decades of land encroachment, cultural pressure, and legal subjugation had pushed Indigenous peoples to the brink. Metacom recognized that isolated resistance was futile. His strategy was to forge a broad pan-tribal alliance against the encroaching Puritan colonies.

King Philip’s War (1675-1678) was one of the bloodiest conflicts in early American history, fought with a ferocity born of desperation. Metacom’s genius lay in his ability to unite disparate tribes, overcome historical animosities, and coordinate widespread attacks on colonial settlements. He employed highly effective guerrilla tactics, exploiting the dense New England forests to his advantage. Native warriors adapted quickly, even adopting some European firearms and tactics.

Metacom’s war was an attempt to reclaim sovereignty and preserve a way of life that was rapidly disappearing. He famously declared, "I am determined not to live until I have no country." Despite initial successes that saw many colonial towns destroyed, the superior numbers and resources of the English, combined with internal divisions and the defection of some Native allies, ultimately led to the defeat of Metacom’s alliance. His sacrifice, however, left an indelible mark, demonstrating the power of a unified Indigenous front, even in the face of overwhelming odds.

Pontiac: Spiritual Revival and Coordinated Uprising

By the mid-18th century, the geopolitical landscape had shifted again. Following the French and Indian War (Seven Years’ War), Great Britain gained control of vast territories in North America, leading to increased colonial expansion and a more aggressive policy towards Native Americans. This era saw the rise of Pontiac, an Ottawa leader whose strategies combined military action with a powerful spiritual and cultural revival.

Inspired by the teachings of the Delaware prophet Neolin, who called for a rejection of European ways and a return to traditional Indigenous practices, Pontiac envisioned a pan-tribal confederacy to drive the British out of the Great Lakes region. His strategy in Pontiac’s War (1763-1766) was remarkable for its coordination. He orchestrated simultaneous attacks on multiple British forts across a vast area, from Michigan to Pennsylvania, showcasing sophisticated planning and communication among diverse nations.

Pontiac employed a mix of siege warfare, deception, and direct assault. His forces famously used the ruse of a lacrosse game to gain entry to Fort Michilimackinac before seizing it. He aimed not just to win battles but to reclaim a cultural identity and spiritual autonomy. Although the uprising ultimately failed to expel the British entirely, it forced them to negotiate and led to the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which temporarily recognized Native land rights west of the Appalachian Mountains—a testament to Pontiac’s strategic impact.

Tecumseh: The Grand Vision of Pan-Indian Sovereignty

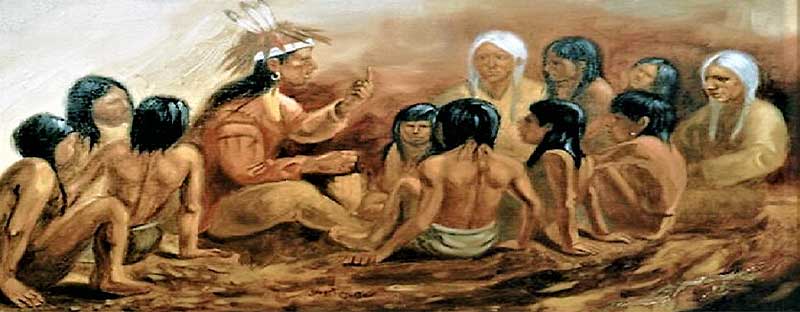

As the United States began its westward expansion in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the Shawnee leader Tecumseh emerged as perhaps the most articulate and formidable proponent of pan-Indian unity. His strategy was a comprehensive vision that encompassed political, military, and spiritual dimensions.

Tecumseh, alongside his brother, Tenskwatawa (The Prophet), sought to unite all Native American tribes east of the Mississippi River into a single, sovereign nation. His political argument was revolutionary: no individual tribe or leader had the right to sell land, as the land was held in common by all Native peoples. "The Great Spirit gave this great island to his red children," Tecumseh proclaimed, "He placed the whites on the other side of the big water. They were not contented with their own, but came to take ours from us." This radical idea challenged the very foundation of U.S. land acquisition.

Militarily, Tecumseh worked tirelessly to build a confederacy, traveling thousands of miles to recruit tribes from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast. He advocated for a unified defense, believing that "A single twig breaks, but the bundle of twigs is strong." His military acumen was evident in his tactical leadership and his ability to inspire loyalty. Spiritually, Tenskwatawa provided the moral and cultural foundation, urging a return to traditional ways and a rejection of alcohol and other corrupting European influences, thereby strengthening communal bonds.

Tecumseh’s confederacy posed a significant threat to American expansion, culminating in his alliance with the British during the War of 1812. His death at the Battle of the Thames in 1813 marked a turning point, effectively dissolving his grand alliance. Yet, Tecumseh’s vision of a united Indigenous nation remains one of the most powerful and enduring expressions of Native American sovereignty.

Beyond the Battlefield: Adaptation and Enduring Legacy

While military resistance often captures the historical imagination, early Native American leaders also employed strategies of adaptation, negotiation, and cultural preservation. They learned European languages, adopted new technologies, and engaged in trade, always seeking to leverage new circumstances for their people’s benefit. Spiritual leaders played a crucial role in maintaining cultural identity and resilience in the face of immense pressure. Even when forced onto reservations, leaders continued to fight for their people’s rights through legal means and political advocacy.

The strategies of these early leaders, though often culminating in tragic outcomes, were far from futile. They delayed European expansion, forced colonial powers to negotiate, shaped geopolitical boundaries, and most importantly, kept alive the flame of Indigenous identity and sovereignty. Their ingenuity, diplomatic prowess, military brilliance, and spiritual depth reveal a complex tapestry of leadership that defies simplistic characterizations.

In understanding the strategic genius of figures like Hiawatha, Powhatan, Metacom, Pontiac, and Tecumseh, we gain a deeper appreciation for the profound challenges and sophisticated responses of Native American nations during a pivotal era. Their enduring legacy reminds us that the history of North America is one of constant interaction, negotiation, and resistance, shaped by the powerful and often unacknowledged contributions of its original inhabitants. Their fight for self-determination continues to resonate, inspiring contemporary struggles for justice and recognition.