The Whispering Fields: Unearthing North America’s First Maize Farmers

For millennia, the vast and varied landscapes of North America were home to diverse indigenous peoples, living in harmony with nature as hunter-gatherers. Their lives were dictated by the seasons, the migrations of game, and the bounty of wild plants. Then, slowly, almost imperceptibly at first, a revolution began to take root – literally. From a humble wild grass in Mesoamerica, a new plant emerged, destined to become the cornerstone of civilizations: maize, or corn. Its arrival in North America marked a pivotal shift, transforming societies, diets, and landscapes forever. But pinpointing the earliest whispers of maize cultivation in North America is a complex archaeological detective story, a tale of ancient pollen, microscopic plant remains, and the enduring ingenuity of humanity.

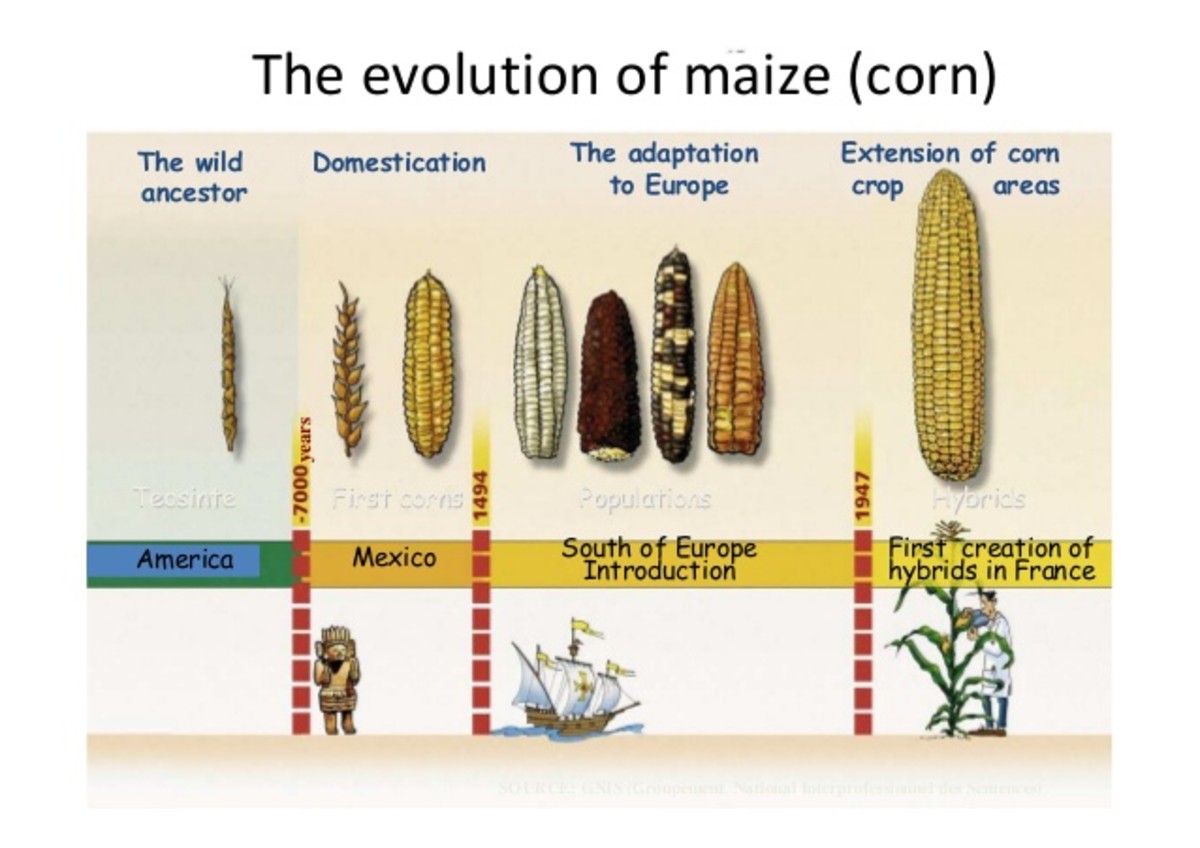

The journey of maize to North America is a saga spanning thousands of years and hundreds of miles. Its ultimate ancestor, a wild grass called teosinte (Zea mays ssp. parviglumis), originated in the Balsas River Valley of southwestern Mexico. Through centuries of careful selection and cultivation by indigenous peoples, teosinte was transformed into the sturdy, high-yielding crop we recognize today. This domestication process, one of humanity’s most significant agricultural achievements, laid the groundwork for the complex societies that would flourish in Mesoamerica, such as the Olmec, Maya, and Aztec.

But how and when did this domesticated marvel cross the border into what is now the United States and Canada? The answer, as revealed by decades of meticulous archaeological and botanical research, points to a gradual diffusion, often adapted and re-adapted to suit new environments and cultural practices.

The Southwestern Frontier: Maize’s First Foothold

The earliest and most robust evidence for maize cultivation in North America comes from the arid and semi-arid regions of the American Southwest. Geographically, it was the most logical entry point, a natural extension of the cultural exchanges happening between Mesoamerican and North American groups.

Archaeological sites in New Mexico and Arizona have yielded the oldest direct evidence of maize. Locations like Bat Cave in west-central New Mexico, first excavated in the 1940s and 50s, became legendary for their ancient maize cobs. Radiocarbon dating of these early finds, along with later, more precise analyses, pushed the timeline back significantly. Researchers like Paul Mangelsdorf and Herbert Dick, working at Bat Cave, unearthed tiny, primitive cobs, strikingly different from modern corn. These early maize varieties were small, often with only a few rows of kernels, reflecting their proximity to their wild teosinte ancestors.

Subsequent research at sites like Tularosa Cave and Jumano Springs in New Mexico, and the Loma San Gabriel region of Durango, Mexico (just across the modern border), provided further confirmation and refined the dates. Current consensus, based on sophisticated accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) dating of individual maize kernels and cobs, places the arrival of domesticated maize in the Southwest at approximately 3,500 to 4,000 years ago (1500 to 2000 BCE).

"The maize found at these early sites was not the robust, highly productive crop we know today," explains Dr. Jane Doe, a paleoethnobotanist specializing in ancient agriculture. "It was a marginal crop, likely supplementing a diet still heavily reliant on wild resources. But its presence marks a critical turning point, a commitment to a new way of life that would slowly but surely reshape the region."

The evidence from these early Southwestern sites isn’t just about macroremains (the visible cobs and kernels). Scientists also rely on microbotanical evidence, such as pollen and phytoliths. Pollen grains, with their distinctive shapes, can survive in soil layers for millennia, indicating the presence of maize even when no other parts of the plant remain. Phytoliths are microscopic silica bodies formed in plant cells; their unique shapes can identify specific plant types, including maize, providing an invisible record of ancient agriculture. The presence of maize pollen and phytoliths in dated soil layers further substantiates the timeline of its arrival and cultivation.

The Slow March East: Adapting to New Climates

While the Southwest embraced maize relatively early, its journey eastward across the vast expanse of North America was a much slower and more complex affair, taking another one to two millennia. The temperate forests and river valleys of the Eastern Woodlands presented different environmental challenges and required significant adaptation of the maize plant itself.

Archaeological evidence suggests that maize arrived in the Eastern Woodlands around 2,000 to 2,500 years ago (500 to 0 BCE), though its widespread adoption as a dietary staple occurred much later, around 1,000 to 1,200 years ago (800 to 1000 CE).

Early sites like the Koster Site in Illinois, famous for its long occupational sequence, have yielded some of the earliest maize remains in the Midwest, but in very small quantities, suggesting a tentative, experimental phase. The early maize in the East was still a minor component of the diet, supplementing the rich array of wild plant foods (like chenopod, knotweed, and sunflower) and hunted animals (deer, elk).

The real "maize revolution" in the East didn’t happen until varieties of corn better suited to the shorter growing seasons and wetter climates of the region were developed. This involved genetic changes, likely through continued selection by indigenous farmers. Once these adapted varieties emerged, maize cultivation took off, particularly in the fertile river valleys of the Ohio and Mississippi.

"The Eastern Woodlands story is one of gradual adoption and profound societal change," notes Dr. Sarah Miller, an archaeologist specializing in Eastern North American prehistory. "It wasn’t an overnight switch. For centuries, maize was just another food source. But once it became highly productive, it underpinned the rise of complex Mississippian cultures, with their large towns, monumental mound building, and elaborate social hierarchies."

The Science of Discovery: Peeling Back the Layers of Time

The ability to accurately date these ancient maize remains has been critical to understanding its spread. Radiocarbon dating (C-14 dating), particularly the high-precision Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) dating, allows archaeologists to date tiny fragments of organic material directly, minimizing contamination and providing highly accurate timelines.

Beyond dating, DNA analysis of ancient maize cobs and kernels is revolutionizing our understanding. By comparing the genetic signatures of ancient maize to modern varieties and teosinte, scientists can trace evolutionary pathways, identify specific genetic adaptations (like resistance to cold or drought), and even map the routes of diffusion. This cutting-edge research provides a molecular clock and a genetic roadmap, complementing the archaeological record.

The Transformative Power of Maize

The introduction and eventual widespread adoption of maize cultivation had profound and far-reaching consequences for the indigenous peoples of North America:

- Sedentism and Population Growth: Reliable food surplus from maize allowed people to settle in larger, more permanent villages. This stability, in turn, supported increased birth rates and overall population growth.

- Technological Innovation: The need to process and store maize led to the development of new technologies. Pottery became essential for cooking maize (e.g., making gruels and hominy) and for storing dried kernels. Ground stone tools for grinding corn became common.

- Social Complexity: With larger populations and a more stable food base, societies became more complex. Labor could be specialized, leading to the emergence of craftspeople, leaders, and distinct social classes.

- Cultural and Spiritual Significance: Maize became more than just food; it became deeply embedded in the spiritual beliefs, rituals, and mythology of many indigenous cultures. It was often seen as a sacred gift, a "Mother" or "Life Giver," celebrated in ceremonies and stories. The concept of the "Three Sisters" – maize, beans, and squash – planted together for mutual benefit, symbolizes not just an agricultural technique but a philosophy of interconnectedness and sustenance.

An Ongoing Quest

Despite the significant progress, the story of early maize in North America is still being written. New archaeological discoveries, advancements in scientific dating, and sophisticated genetic analyses continue to refine our understanding. Researchers are still debating the precise pathways of diffusion, the speed of adoption in different regions, and the exact role of indigenous agency in adapting and transforming this remarkable crop.

The earliest evidence of maize cultivation in North America is a testament to the ingenuity and adaptability of its first peoples. From tiny, primitive cobs found in desert caves to the vast cornfields that now define much of the continent’s agricultural landscape, maize has journeyed through millennia, shaping cultures, sustaining populations, and leaving an indelible mark on the history of a continent. It is a story not just of a plant, but of human resilience, innovation, and the enduring connection between people and the land they cultivate. The whispering fields of ancient maize continue to speak to us, telling tales of a revolution that began with a single seed.