A Silent Scourge: Disease Outbreaks Threaten Turtle Populations Across Turtle Island

For countless Indigenous peoples, Turtle Island – the ancestral name for North America – is more than just a landmass; it is a sacred entity, a living being upon whose back humanity resides. The turtle, in particular, is a foundational figure, a symbol of longevity, wisdom, and the very creation of the world. Yet, this revered creature, central to so many spiritual narratives, is under an unprecedented siege. Across the wetlands, forests, and coastlines of this continent, a silent scourge of disease outbreaks is decimating turtle populations, pushing species already teetering on the brink further towards oblivion.

The crisis is multifaceted, driven by a complex interplay of environmental degradation, climate change, human activity, and the insidious spread of pathogens. From the ancient Blanding’s turtle navigating the Great Lakes region to the majestic sea turtles gracing coastal waters, the health of these chelonians is a critical barometer for the health of Turtle Island itself.

The Invisible Enemy: Key Pathogens and Their Impact

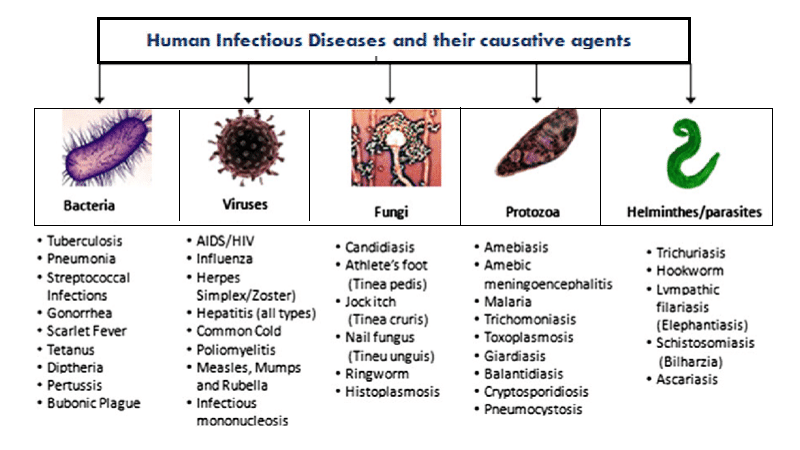

Disease outbreaks in turtle populations are not new phenomena, but their frequency, intensity, and geographic spread have escalated dramatically in recent decades. Several pathogens stand out as significant threats:

-

Ranavirus: Perhaps one of the most devastating, ranaviruses are highly virulent pathogens that affect amphibians, reptiles, and fish. They cause systemic infections, leading to hemorrhagic disease, organ failure, and rapid death. Outbreaks often result in mass mortality events, particularly in freshwater turtle species. "Ranaviruses are responsible for some of the most dramatic mass mortality events observed in ectothermic vertebrates globally," explains Dr. Anya Sharma, a leading chelonian veterinarian specializing in disease ecology. "They can wipe out entire cohorts of juvenile turtles, effectively sterilizing a generation and severely impacting long-term population viability." The rapid progression of the disease means that by the time affected individuals are found, it’s often too late for intervention, leaving conservationists to count the dead.

-

Mycoplasma: Mycoplasma agassizii, primarily known for its devastating impact on desert tortoises in the southwestern United States, causes Upper Respiratory Tract Disease (URTD). This chronic, debilitating illness manifests as nasal discharge, ocular swelling, lethargy, and severe emaciation. While less acutely fatal than ranavirus, its chronic nature weakens individuals, making them susceptible to other infections, predation, and environmental stressors. The spread of Mycoplasma is often linked to human translocation of turtles, where seemingly healthy individuals can be asymptomatic carriers, introducing the pathogen to naive populations.

-

Shell Disease: A broad category encompassing various bacterial and fungal infections of the carapace and plastron, shell disease is a pervasive issue. It can range from superficial lesions to deep, ulcerative infections that expose bone, leading to severe pain, compromised buoyancy, and eventual death. While often secondary to underlying stressors like poor water quality, nutritional deficiencies, or injury, severe outbreaks can be primary drivers of mortality. For species like the Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata) or the Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta), which rely on pristine aquatic and terrestrial habitats, compromised shell integrity is a death sentence.

-

Fibropapillomatosis (FP): While primarily affecting sea turtles (especially green sea turtles), FP is a stark example of disease emergence linked to environmental factors. Characterized by the growth of debilitating tumors on soft tissues and internal organs, FP severely impairs a turtle’s ability to forage, swim, and evade predators. Research strongly suggests a link between FP prevalence and coastal pollution, nutrient runoff, and changes in water temperature, indicating that human activities are directly contributing to this horrifying affliction.

Drivers of the Crisis: A Web of Interconnected Threats

The rise in disease outbreaks is not an isolated phenomenon but rather a symptom of a larger ecological imbalance. Several interconnected factors exacerbate the problem:

-

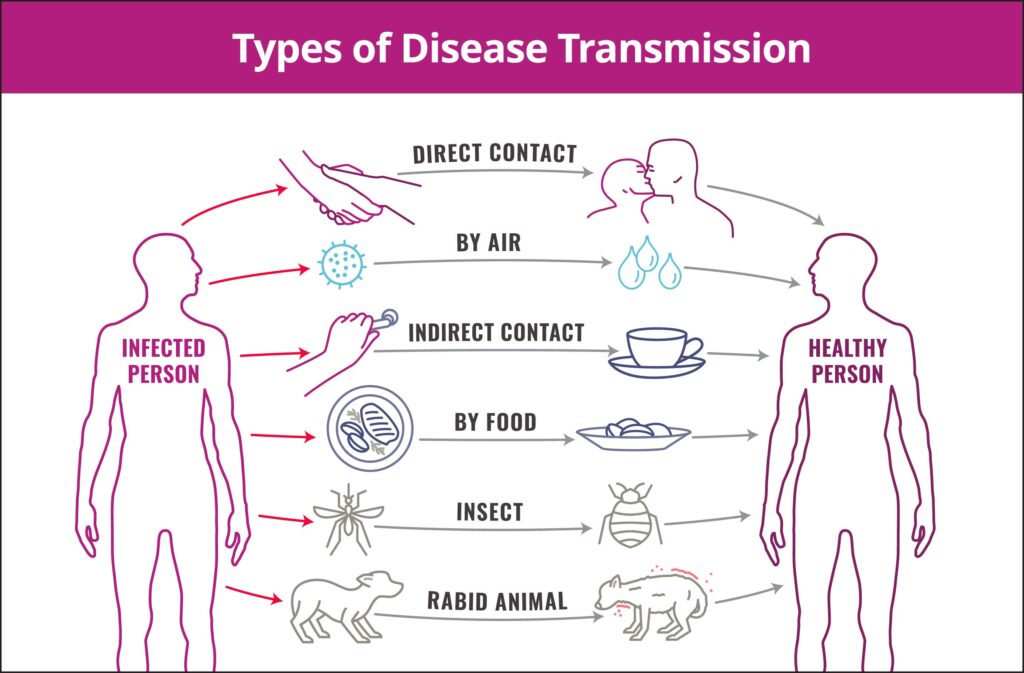

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: As wetlands are drained, forests cleared, and coastlines developed, turtle habitats shrink and become fragmented. This forces turtles into smaller, denser populations, increasing contact rates and accelerating disease transmission. Fragmented populations also suffer from reduced genetic diversity, making them less resilient to pathogens.

-

Climate Change: Rising global temperatures exert immense physiological stress on turtles. Warmer water temperatures can favor pathogen growth, while altered precipitation patterns lead to droughts or floods, disrupting breeding cycles and food availability. Temperature-dependent sex determination, common in many turtle species, is also threatened, potentially leading to skewed sex ratios and reduced reproductive success. Stressed individuals have compromised immune systems, making them more vulnerable to infection.

-

Pollution: Chemical runoff from agriculture and industry, plastic debris, and pharmaceuticals contaminate aquatic environments. These pollutants can act as immunosuppressants, directly harming turtles and making them more susceptible to disease. The link between fibropapillomatosis in sea turtles and coastal pollution is a chilling example of this direct correlation.

-

Human Interaction and Pet Trade: The illegal and unregulated pet trade is a major vector for disease transmission. Turtles captured from the wild or bred in unsanitary conditions are often stressed and exposed to novel pathogens. When these animals are released or escape into wild populations, they can introduce devastating diseases to naive local turtles, leading to rapid, widespread outbreaks. Road mortality, recreational boating, and even well-meaning but ill-informed handling by humans also contribute to stress and injury, predisposing turtles to infection.

Turtle Island’s Warning: A Cultural and Ecological Imperative

For Indigenous peoples, the health of the turtle is intrinsically linked to the health of the land and all its inhabitants. "Our Elders teach us that the turtle carries the weight of the world on its back," says Elder Thomas Rivers, a knowledge keeper from the Anishinaabe nation. "When the turtles suffer, Turtle Island suffers. Their sickness is a warning to us all that our relationship with the land is out of balance." This profound understanding positions turtles not just as an ecological component but as a spiritual indicator species. Their decline represents not only a loss of biodiversity but a deep cultural wound and a signal of systemic environmental degradation.

Indeed, turtles play vital ecological roles. As omnivores, they help control insect populations, disperse seeds, and contribute to nutrient cycling. Their long lifespans mean they are significant contributors to ecosystem stability, and their absence creates trophic cascades that can destabilize entire wetlands and aquatic systems. "An estimated 90% of freshwater turtle species on Turtle Island are considered imperiled or extinct," highlights a sobering report from the IUCN Red List. This statistic underscores the urgency of the situation and the profound loss unfolding across the continent.

Responding to the Crisis: Science, Stewardship, and Sovereignty

Addressing the escalating disease outbreaks requires a multi-pronged approach that integrates scientific research, conservation action, and Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge (TEK).

Veterinary pathologists and disease ecologists are at the forefront, working to identify new pathogens, understand transmission dynamics, and develop diagnostic tools. Genetic sequencing helps trace the origins and spread of diseases, informing targeted interventions. Field researchers conduct monitoring programs, tracking population health and identifying potential outbreak hotspots.

Conservation efforts include habitat restoration, creating protective barriers to prevent road mortality, and head-starting programs where eggs are incubated in protected environments and hatchlings released into the wild once they are more robust. Rehabilitation centers play a crucial role in treating sick or injured turtles, although the sheer scale of outbreaks often overwhelms their capacity.

Crucially, the "One Health" approach is gaining traction – recognizing that the health of humans, animals, and the environment are inextricably linked. This collaborative, cross-sectoral approach is essential for understanding and mitigating complex disease threats. It necessitates cooperation between veterinarians, wildlife biologists, public health officials, and land managers.

Furthermore, integrating Indigenous knowledge and land stewardship practices is paramount. TEK offers centuries of observation and understanding of ecological processes, providing invaluable insights into turtle behavior, habitat requirements, and historical population trends. Many Indigenous communities are actively involved in turtle conservation, drawing upon their ancestral responsibilities to protect these sacred beings. Respecting Indigenous sovereignty and fostering true partnerships in conservation efforts is not just ethical; it is scientifically and ecologically imperative.

The Path Forward: Urgent Action for a Sacred Species

The future of turtles on Turtle Island hangs in a precarious balance. The silent scourge of disease outbreaks, amplified by human-induced environmental changes, demands immediate and sustained action. This includes:

- Strengthening Disease Surveillance: Investing in more robust monitoring programs to detect outbreaks early and prevent widespread transmission.

- Targeted Research: Funding research into turtle immunology, pathogen evolution, and the specific environmental triggers for outbreaks.

- Habitat Protection and Restoration: Aggressively protecting remaining pristine habitats and restoring degraded ones to reduce stress on populations.

- Stricter Regulations on the Pet Trade: Implementing and enforcing stricter laws to curb the illegal wildlife trade and prevent the spread of disease.

- Public Education: Raising awareness about the importance of turtles, the threats they face, and how individuals can contribute to their protection (e.g., never releasing pet turtles into the wild).

- Collaborative Conservation: Fostering genuine partnerships between scientific institutions, government agencies, local communities, and Indigenous nations, recognizing that collective action is the only way forward.

The turtle, a symbol of resilience and the foundation of a continent, is sending a clear message. Its struggle against disease is a poignant reflection of a larger ecological crisis. To protect these ancient mariners is to protect the very fabric of Turtle Island, ensuring that the wisdom and longevity they represent continue to inspire generations to come. The time for decisive action is now, before the silent scourge claims more of these sacred creatures, and with them, a vital piece of our collective heritage.