Echoes of Power: The Development of Complex Social Hierarchies in Ancient Americas

By

Beneath the dense rainforest canopies of Mesoamerica, atop the dizzying heights of the Andes, and across the vast plains of North America, ancient civilizations rose and fell, leaving behind not just monumental ruins but also the indelible imprint of intricate social structures. Far from being egalitarian societies, many ancient American cultures developed highly complex social hierarchies, characterized by specialized labor, inherited status, powerful elites, and often, divine kingship. These structures, built on foundations of agricultural innovation, ritual practice, and sometimes fierce conquest, shaped the lives of millions and continue to fascinate scholars today.

The journey towards social complexity was not a singular event but a gradual evolution, driven by diverse environmental pressures and opportunities. Early hunter-gatherer groups, typically egalitarian, began to settle as they mastered agriculture. With surplus food came population growth, the need for organized labor, and eventually, the rise of individuals or groups who could manage these new demands.

The First Seeds of Stratification: Olmec and Norte Chico

Some of the earliest evidence for nascent social stratification emerges in Mesoamerica with the Olmec civilization, flourishing along the Gulf Coast of Mexico from roughly 1600 to 400 BCE. The Olmec are renowned for their colossal basalt heads, massive sculptures that can weigh up to 40 tons, depicting individualized rulers. The sheer effort required to quarry, transport, and carve these monuments speaks volumes about an organized labor force directed by powerful leaders.

"The colossal heads of the Olmec are not just artistic marvels; they are tangible proof of a society capable of marshalling immense human and material resources," notes Dr. Sarah C. Miller, an archaeologist specializing in early Mesoamerican cultures. "This level of organization implies a leadership with significant authority and the ability to command tribute or labor from a broad population."

Beyond the heads, Olmec sites like San Lorenzo and La Venta reveal planned ceremonial centers, elaborate tombs with jade offerings, and sophisticated drainage systems. These features point to a society where certain individuals held privileged access to resources, spiritual knowledge, and the power to mobilize their communities for grand projects, laying the groundwork for future Mesoamerican civilizations.

Concurrently, in the Andean region of South America, the Norte Chico civilization (also known as Caral-Supe) in present-day Peru developed around 3000-1800 BCE, predating the Olmec. What makes Norte Chico remarkable is its complexity without pottery or extensive warfare. Instead, their social organization seems to have revolved around massive monumental architecture, including stepped pyramids and sunken circular plazas, suggesting a society unified by religious or ceremonial practices. The construction of these structures implies a leadership capable of coordinating large labor forces, likely through a blend of religious authority and practical administration, even in the absence of obvious military power.

Mesoamerican Grandeur: Maya, Teotihuacan, and Zapotec

As centuries passed, the seeds of complexity blossomed into the vibrant, intricate societies of the Classic Mesoamerican period (c. 250-900 CE).

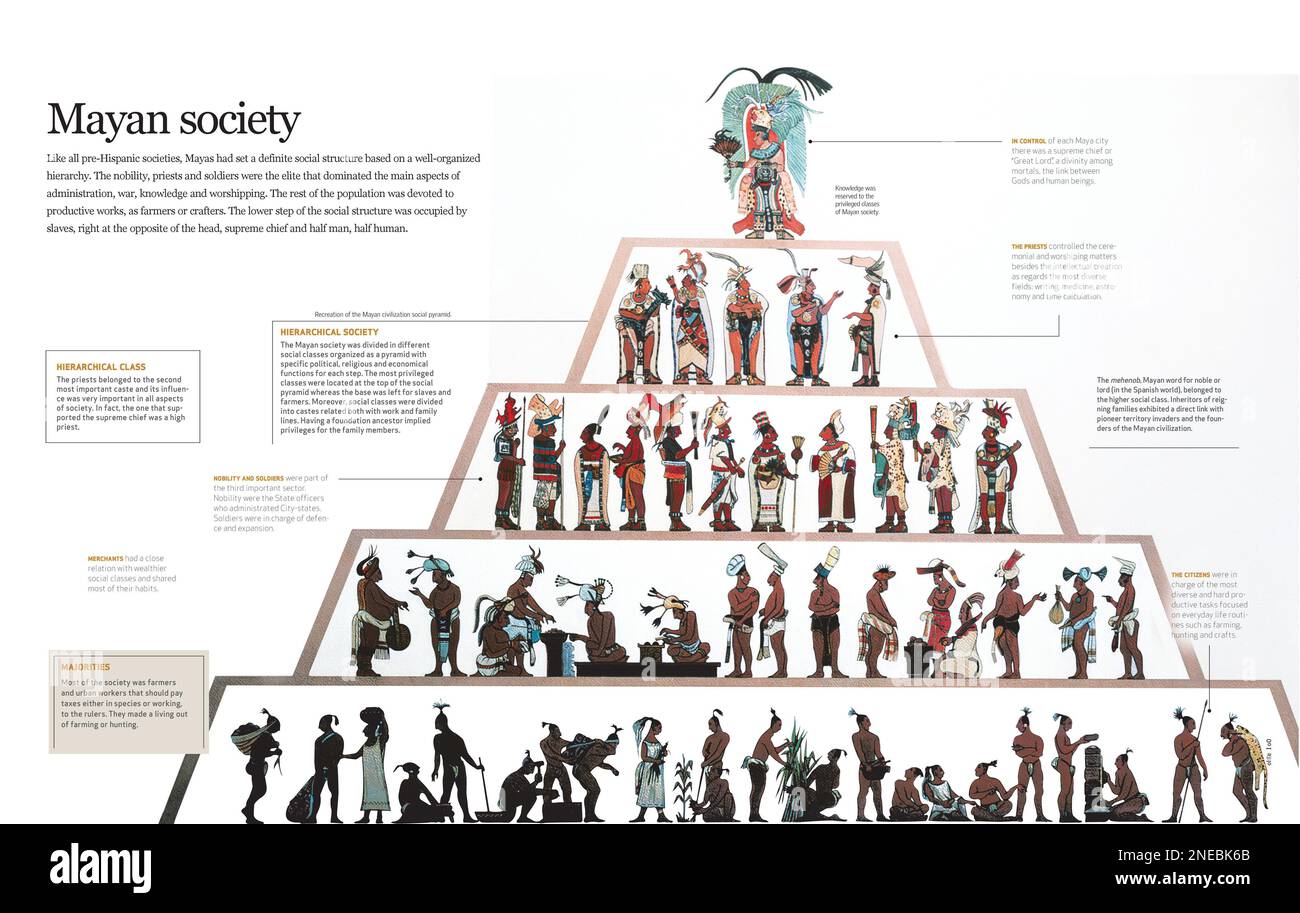

The Maya civilization, spread across southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras, developed a highly stratified society centered around powerful city-states. At the apex of Maya society was the k’uhul ajaw or "divine lord," a king who served as both a political and spiritual leader, often believed to be a direct descendant of the gods. Their power was legitimized through elaborate rituals, public ceremonies, and the construction of towering temples and palaces that proclaimed their divine connection. Stelae, carved stone monuments, frequently depict these rulers in victorious poses or communing with deities, reinforcing their authority.

"Maya kings were not just administrators; they were cosmological anchors," explains Dr. Alejandro Vargas, a Mayanist historian. "Their very existence was believed to maintain the cosmic order, connecting the human realm to the divine. This ideology provided an incredibly potent justification for their absolute power and the rigid social hierarchy beneath them."

Beneath the divine kings were a hereditary nobility, scribes, priests, skilled artisans, warriors, and a vast commoner population who provided agricultural labor and tribute. Warfare was endemic, often serving not just to acquire territory but also to capture elites for ritual sacrifice, further reinforcing the power of the victorious king and their gods.

To the west, in the Valley of Mexico, lay Teotihuacan (c. 100 BCE – 550 CE), one of the largest cities in the ancient world, home to perhaps 125,000-200,000 people at its peak. Unlike the city-state model of the Maya, Teotihuacan appears to have been a highly centralized, bureaucratic state. Its social hierarchy was manifested in its meticulously planned urban layout, with grand avenues, colossal pyramids (like the Pyramid of the Sun and Moon), and distinct residential compounds.

Archaeological evidence suggests a diverse population, including specialized craftspeople (potters, obsidian workers), merchants, priests, and an administrative elite. While Teotihuacan lacks the explicit depictions of individual rulers seen in Maya art, the monumental scale of its public works and the uniformity of its urban planning point to a powerful, perhaps collegial, ruling class that commanded immense resources and labor. The city’s widespread influence across Mesoamerica, evident in its unique art and architectural styles, further underscores its reach and organizational prowess.

In the Oaxaca Valley, the Zapotec civilization established its capital at Monte Albán (c. 500 BCE – 800 CE), a grand city built on a flattened mountaintop overlooking the valley. Monte Albán’s strategic location and impressive public architecture, including temples, ballcourts, and the famous "Danzantes" (carved figures depicting sacrificed captives), highlight a militaristic elite that consolidated control over the valley’s resources and populations. The Zapotec developed one of Mesoamerica’s earliest writing systems, primarily used to record dynastic histories and conquests, further solidifying the power of the ruling families.

Andean Empires: From Moche to Inca

South America’s Andes region also witnessed the rise of highly stratified societies, often driven by the need to manage diverse ecological zones and extensive irrigation systems.

The Moche civilization (c. 100-800 CE) of coastal Peru is renowned for its exquisite pottery and sophisticated metallurgy, which depict a society ruled by powerful warrior-priests. The discovery of the Lord of Sipán’s tomb in 1987 revealed an astonishing array of gold, silver, and copper artifacts, elaborate regalia, and sacrificial victims, offering unparalleled insight into the wealth and ritual power of Moche elites. These rulers controlled vast agricultural lands, organized impressive public works (like the Huaca del Sol and Huaca de la Luna), and maintained their authority through a combination of military prowess and religious ideology, which often included human sacrifice.

Later, the Wari (c. 600-1000 CE) and Tiwanaku (c. 500-1000 CE) empires emerged in the highlands, demonstrating complex state-level organization across vast territories. Both cultures developed sophisticated administrative systems, extensive road networks, and distinct forms of monumental architecture, indicating a powerful centralized authority that managed resources and populations across diverse ecological zones. Their influence set the stage for the ultimate Andean empire: the Inca.

The Inca Empire (c. 1400-1532 CE) was the largest pre-Columbian empire in the Americas, stretching over 4,000 km along the Andes. Its social hierarchy was incredibly rigid and pervasive. At its pinnacle was the Sapa Inca, the divine emperor, considered a descendant of the sun god Inti. Beneath him were a vast bureaucracy of nobles, priests, military leaders, and administrators, often drawn from the royal family or favored ethnic groups.

The Inca managed their vast empire through a system known as mit’a, a form of public service or labor tribute. Rather than paying taxes in goods, commoners contributed labor to state projects, such as building roads, terraces, or temples, or serving in the military. This sophisticated system allowed the Inca to mobilize massive workforces for monumental projects like Machu Picchu and to maintain a vast network of infrastructure. The quipu, a system of knotted cords, was used for record-keeping and administration, further demonstrating the empire’s advanced organizational capabilities.

"The Inca Empire was a marvel of social engineering," states Dr. Elena Ramirez, an Andean historian. "Their ability to integrate diverse ethnic groups, manage resources across extreme altitudes, and maintain control through a combination of ideological legitimacy and practical administration, all without a written language in the traditional sense, is truly astonishing."

North American Complexities: Cahokia and Chaco Canyon

While perhaps less widely known than their Mesoamerican and Andean counterparts, cultures in ancient North America also developed significant social hierarchies.

The Mississippian culture (c. 800-1600 CE), primarily in the southeastern and midwestern United States, built vast earthwork mounds and complex chiefdoms. Cahokia, near modern-day St. Louis, Missouri, was its largest and most influential center, with a peak population estimated between 10,000 and 20,000 people. Cahokia was a highly stratified society, evident in its monumental architecture, particularly Monks Mound, the largest prehistoric earthen structure in the Americas. Elite burials, such as the one in Mound 72, containing a principal male buried on a bed of shell beads, surrounded by sacrificed individuals and grave goods, strongly indicate a ruling class with inherited status and immense power. This was a society where a select few commanded the labor and loyalty of many.

In the American Southwest, the Ancestral Puebloans of Chaco Canyon (c. 850-1250 CE) developed a unique form of social organization. While not an empire in the same vein as the Inca, Chaco Canyon served as a major regional center, characterized by its "great houses"—massive multi-story complexes of stone masonry. The construction of these buildings, often aligned with astronomical events, and the extensive network of roads connecting Chaco to outlying communities, suggest a complex system of social coordination and ritual authority. While the exact nature of Chaco’s hierarchy is still debated, the significant investment in monumental architecture and the coordination required for its construction point to a powerful elite, possibly a priestly class, who held sway over a wide area through religious and economic influence.

Mechanisms of Maintenance and Legitimacy

Across the Americas, the maintenance of these complex social hierarchies relied on several interlocking mechanisms:

- Ideology and Religion: Rulers were often seen as divine or divinely appointed, connecting the earthly realm to the cosmic order. This provided an unshakeable justification for their power.

- Economic Control: Elites controlled access to vital resources (water, fertile land, trade goods) and organized labor for agricultural production and monumental construction.

- Military Power: Warfare was often used to expand territory, capture resources, and enforce tribute, with successful warriors gaining status and power.

- Ritual and Ceremony: Public rituals, often involving elaborate costumes, music, and even sacrifice, reinforced the power of the elite and unified the populace under a shared belief system.

- Monumental Architecture: Pyramids, temples, and palaces served as tangible symbols of power, wealth, and the ability to command vast human resources.

Conclusion

The development of complex social hierarchies in ancient Americas was a testament to human ingenuity, adaptability, and the perennial quest for power and order. From the colossal heads of the Olmec to the sprawling Inca Empire, these societies devised sophisticated systems of governance, labor organization, and ideological control that allowed them to build some of the most awe-inspiring civilizations in human history. While the specific manifestations differed across continents and cultures, the underlying principles of stratification, specialization, and the legitimization of authority offer a profound insight into the diverse pathways human societies have taken towards complexity. Studying these ancient echoes of power not only illuminates our past but also provides valuable perspectives on the enduring dynamics of social structure and leadership in our present world.