Beyond the Textbook: Crafting Culturally Responsive Curricula for Tribal Schools

In the remote corners of the world, where ancient traditions whisper through dense forests and across vast plains, millions of indigenous children embark on a journey that often feels like navigating a foreign land: formal education. For too long, mainstream curricula, designed for dominant cultures and urban environments, have inadvertently alienated tribal students, leading to high dropout rates, diminished self-esteem, and a tragic erosion of invaluable cultural heritage. The imperative is clear: education for tribal communities must transcend the one-size-fits-all model and embrace a culturally responsive approach, meticulously developed to resonate with their unique identities, languages, and ways of knowing.

This is not merely an academic exercise; it is a fundamental human right and a cornerstone of sustainable development. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), adopted in 2007, unequivocally states that "Indigenous peoples have the right to establish and control their educational systems and institutions providing education in their own languages, in a manner appropriate to their cultural methods of teaching and learning." This global consensus underscores the profound need for a paradigm shift in curriculum development for tribal schools, moving from assimilationist models to those that empower, preserve, and celebrate.

The Disconnect: Why Mainstream Fails

The challenges faced by tribal students in mainstream educational settings are multifaceted and deeply rooted. Foremost among them is the language barrier. Many tribal children enter school speaking only their indigenous language, encountering a curriculum delivered entirely in a dominant national or regional language. This immediately places them at a severe disadvantage, hindering comprehension, participation, and cognitive development. UNESCO estimates that over 4,000 of the world’s approximately 7,000 languages are indigenous, highlighting the immense linguistic diversity often overlooked by standardized education systems.

Beyond language, the cultural content of mainstream curricula often presents a worldview alien to tribal children. Histories, geographies, social structures, and scientific explanations are typically presented from a dominant cultural perspective, sidelining or even denigrating indigenous knowledge systems. Traditional stories are replaced by foreign fables, local heroes by national figures, and indigenous practices by modern concepts that may hold little relevance to their daily lives. This cultural dissonance can lead to a sense of alienation, rendering education irrelevant and unengaging. "When children don’t see themselves reflected in the curriculum," notes one indigenous educator, "they begin to believe they don’t belong, or that their culture is inferior. It’s a silent form of cultural violence."

Furthermore, pedagogical approaches in mainstream schools often emphasize rote learning and individual competition, which can clash with tribal learning styles that may prioritize oral traditions, collaborative learning, experiential engagement, and respect for elders as knowledge holders. The lack of culturally sensitive teachers, often from outside the tribal community, exacerbates these issues, as they may lack understanding of local customs, languages, and socio-economic realities.

The Imperative for Culturally Responsive Curricula

Developing a culturally responsive curriculum for tribal schools is not about isolating these communities; rather, it’s about building a robust foundation upon which children can confidently engage with the wider world while rooted in their heritage. It is about fostering critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and a sense of agency that allows them to navigate both their traditional ways of life and the demands of modernity.

The core principles driving this development are:

-

Multilingual Education (MLE): This is perhaps the most critical component. MLE models advocate for initial instruction in the child’s mother tongue, gradually transitioning to the dominant language as they develop foundational literacy and numeracy skills. This "bridging" approach allows children to learn in a language they understand, building confidence and cognitive abilities, which then facilitate learning in a second language. Countries like India, with its vast linguistic diversity, have seen promising results from MLE programs, demonstrating significant improvements in attendance, retention, and learning outcomes in tribal schools.

-

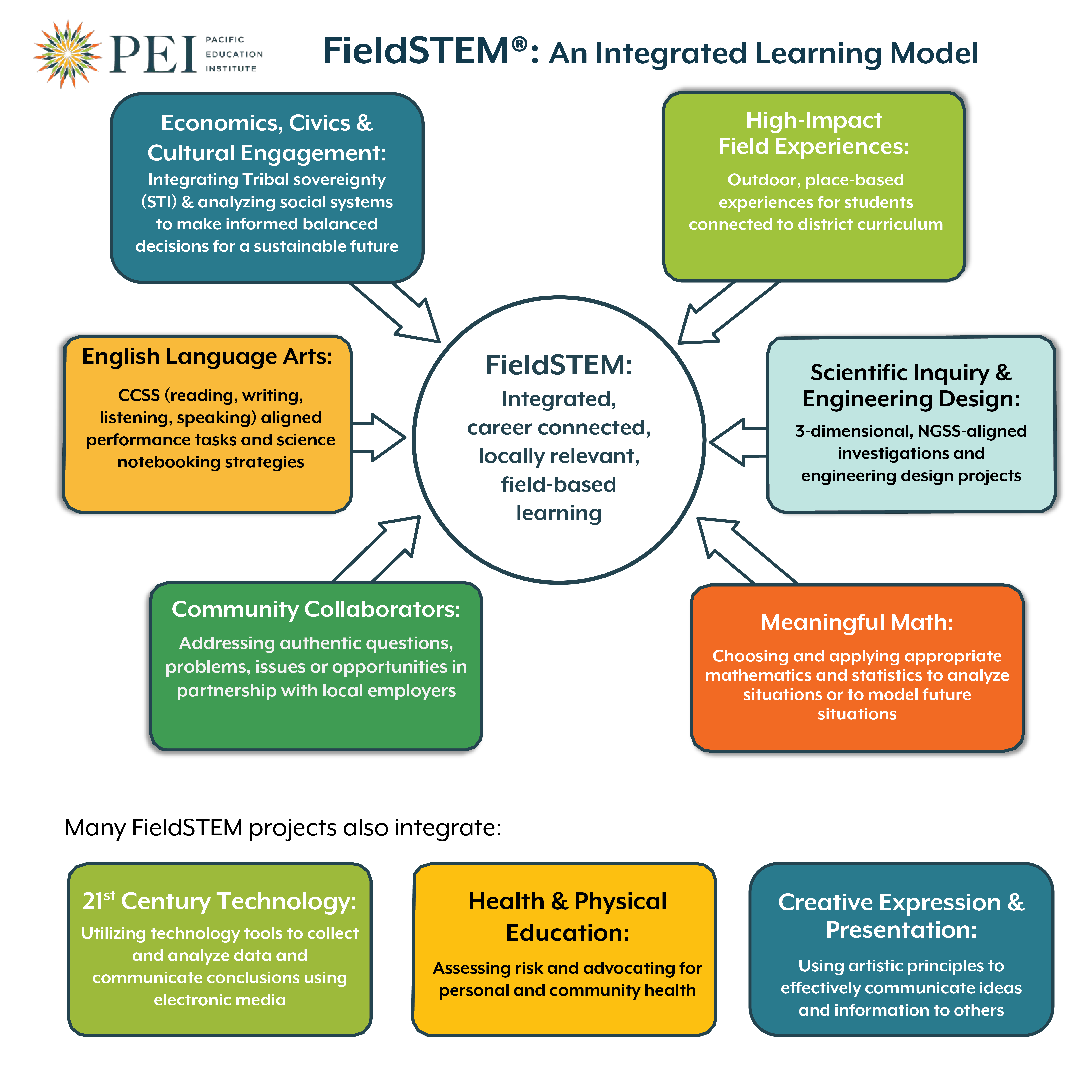

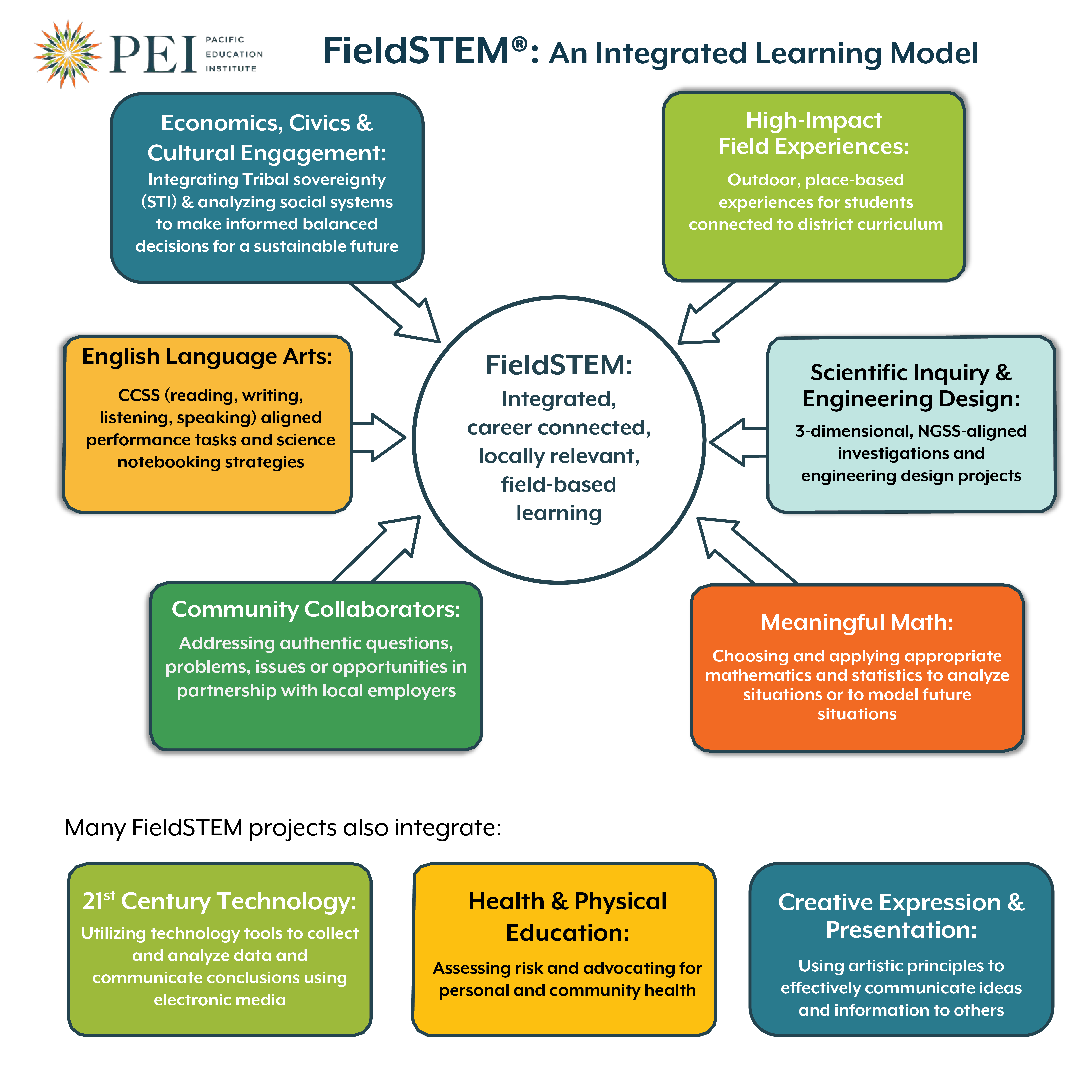

Contextual Relevance and Local Knowledge Integration: The curriculum must be woven with threads of local culture, history, environment, and traditional knowledge. This involves:

- Local History and Oral Traditions: Incorporating tribal histories, legends, and folklore passed down through generations.

- Ethnobotany and Traditional Ecological Knowledge: Teaching about local flora and fauna, sustainable practices, and traditional medicine. For instance, a science lesson could explore the ecological balance of a local forest from both a scientific and an indigenous perspective.

- Traditional Arts, Crafts, and Skills: Integrating local artistic expressions, music, dance, and practical skills like weaving, pottery, or traditional agriculture. This not only preserves cultural forms but also provides vocational relevance.

- Community Governance and Social Structures: Understanding the traditional governance systems and social norms of their community.

-

Community Participation and Ownership: A truly effective curriculum cannot be imposed from the outside. It must be co-created with the active involvement of tribal elders, parents, community leaders, and local educators. This ensures authenticity, relevance, and builds a sense of ownership, making the school an integral part of the community rather than an alien institution. Elders, as living libraries of knowledge, become invaluable resources, sharing stories, skills, and wisdom.

-

Culturally Appropriate Pedagogy: Teaching methods must align with tribal learning styles. This often means embracing:

- Experiential Learning: Learning by doing, through field trips to local sites, practical demonstrations, and hands-on projects related to local life.

- Collaborative Learning: Group activities, peer teaching, and community-based projects that foster cooperation over individual competition.

- Storytelling and Oral Narratives: Utilizing the powerful tradition of storytelling as a primary teaching tool.

- Holistic Learning: Integrating different subjects rather than strictly compartmentalizing them, reflecting the interconnectedness often found in indigenous worldviews.

-

Teacher Training and Sensitization: Teachers, whether from the tribal community or outside, must be trained in culturally responsive pedagogy, local languages, and sensitized to tribal cultures and challenges. Recruiting and training teachers from within the tribal community is particularly effective, as they bring inherent cultural understanding and serve as role models.

Challenges in Implementation

Despite the clear benefits, implementing culturally responsive curricula faces significant hurdles:

- Resource Constraints: Developing new curricula, creating culturally appropriate textbooks and learning materials in multiple indigenous languages, and training teachers require substantial financial and human resources, often scarce in remote tribal areas.

- Policy and Political Will: Shifting from centralized, standardized education systems to decentralized, culturally specific ones requires strong political will and supportive national policies. Resistance can come from those who fear fragmentation or believe in a uniform national identity.

- Material Development: The sheer number of indigenous languages makes it a monumental task to develop high-quality, relevant educational materials for each.

- Teacher Availability: Attracting and retaining qualified teachers, especially those proficient in indigenous languages, in remote areas remains a persistent challenge.

- Standardization vs. Customization: Balancing the need for local relevance with national educational standards and ensuring pathways to higher education can be complex.

Glimmers of Hope and Pathways Forward

Yet, amidst these challenges, success stories abound. In Canada, First Nations communities are increasingly taking control of their education, developing curricula that embed Indigenous knowledge and languages, leading to improved outcomes and cultural revitalization. In parts of Latin America, Intercultural Bilingual Education (IBE) programs have demonstrated that mother-tongue instruction coupled with culturally relevant content significantly boosts academic performance and cultural pride. India’s National Education Policy 2020 explicitly advocates for mother tongue instruction and the integration of local knowledge, signalling a crucial policy shift.

The path forward requires a concerted effort from governments, educational institutions, NGOs, and crucially, tribal communities themselves. Key strategies include:

- Dedicated Funding: Allocating specific budgets for curriculum development, material production, and teacher training in tribal schools.

- Policy Frameworks: Enacting legislation that supports and mandates culturally responsive education, including MLE.

- Partnerships: Fostering collaborations between educational experts, linguists, anthropologists, and tribal elders to co-create curricula.

- Technology Leverage: Utilizing digital tools where feasible to develop and disseminate learning materials, train teachers remotely, and connect tribal schools.

- Research and Evaluation: Continuously evaluating the effectiveness of these curricula and adapting them based on feedback and outcomes.

Conclusion

The journey of curriculum development for tribal schools is a testament to the belief that education should be a liberating force, not an instrument of assimilation. It is about recognizing the inherent value and wisdom embedded in every culture and creating learning environments where children feel seen, valued, and empowered. As Professor Linda Tuhiwai Smith, a distinguished Māori educationalist, aptly states, "Research is not an innocent or pure activity. It is knowledge about the Other that is then used to control the Other." In contrast, culturally responsive curriculum development is about empowering "the Other" to control their own knowledge, their own narrative, and their own future.

By prioritizing multilingualism, integrating local knowledge, fostering community participation, and embracing culturally appropriate pedagogies, we can transform tribal schools into vibrant centers of learning that not only equip children with essential skills for the modern world but also safeguard and celebrate the rich tapestry of human diversity. This investment is not just in education; it is an investment in human dignity, cultural resilience, and a more equitable and inclusive global future. The time to move beyond the textbook and into the heart of tribal wisdom is now.