Turtle Island: A Continent Forged in Resilience – Indigenous Peoples Confront Crisis and Chart a Future

Turtle Island, the ancient name given by many Indigenous peoples to the North American continent, is a land rich in history, culture, and profound spiritual connection. Today, it remains a vibrant crucible where Indigenous nations, armed with ancestral wisdom and unyielding resilience, navigate a complex landscape of persistent challenges, systemic injustices, and a powerful resurgence of self-determination. Far from being relegated to history, the struggles and triumphs of Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island are central to its contemporary narrative, shaping its environmental future, legal frameworks, and moral conscience.

The very concept of Turtle Island embodies a worldview that prioritizes balance, reciprocity, and a deep respect for all living things – principles often at odds with the extractivist and colonial systems that have dominated the continent for centuries. Current events underscore this fundamental tension, manifesting in land and resource conflicts, the ongoing reckoning with historical trauma, the fight for safety and equity, and the innovative ways Indigenous communities are leading on climate action and cultural revitalization.

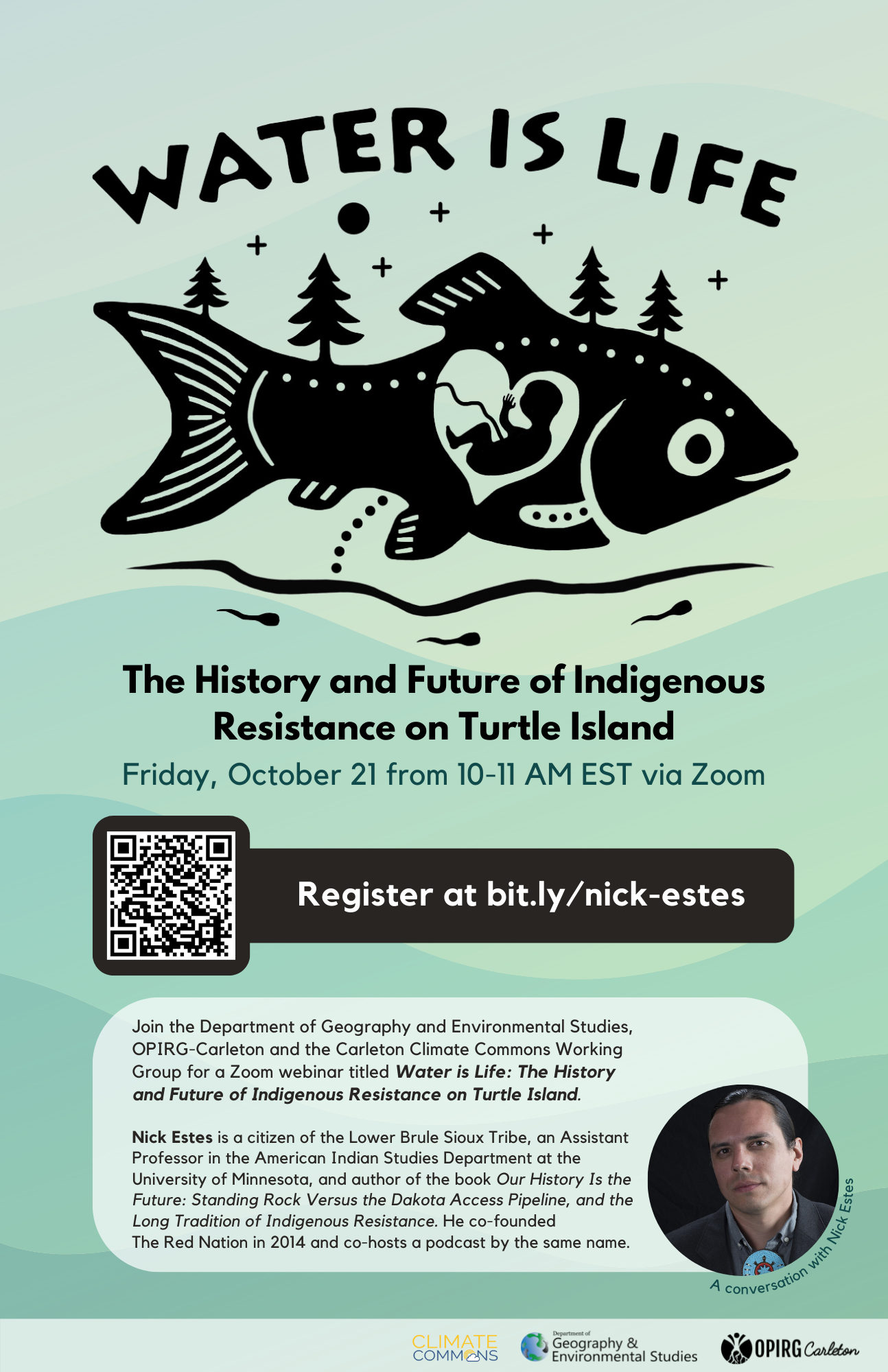

One of the most visible and contentious arenas for Indigenous sovereignty on Turtle Island is the battle over land and resource extraction. Across the continent, Indigenous nations are asserting their inherent rights and treaty obligations against powerful corporate and governmental interests. From the frozen reaches of the Arctic to the temperate rainforests of the Pacific Northwest, and the vast plains, pipelines, mines, and logging operations continue to threaten sacred sites, traditional territories, and vital ecosystems.

A prime example is the ongoing resistance by the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs against the Coastal GasLink (CGL) pipeline in so-called British Columbia, Canada. Despite court injunctions and repeated police interventions, the Wet’suwet’en, upholding their ancient governance structure, have maintained that the project lacks their free, prior, and informed consent for passage through their unceded territory. This conflict highlights a critical distinction: while elected band councils often hold jurisdiction over reserves, hereditary chiefs represent a deeper, pre-colonial form of governance over traditional territories, a distinction frequently ignored by Canadian law. The CGL struggle is not merely about a pipeline; it is a profound assertion of Wet’suwet’en inherent sovereignty and an indictment of Canada’s failure to truly implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Similarly, in the United States, Indigenous nations continue to lead fights against projects like the Enbridge Line 3 pipeline in Minnesota, which faced years of fierce opposition from Anishinaabe water protectors and allies. The struggle, rooted in treaty rights and environmental justice, aimed to prevent the pipeline from crossing pristine waters and sensitive wild rice beds – a staple food and sacred plant for the Anishinaabe. Although Line 3 was ultimately completed, the protracted resistance brought national and international attention to the disproportionate impact of fossil fuel infrastructure on Indigenous communities and the strength of Indigenous-led environmental movements. As Winona LaDuke, an Anishinaabe activist and executive director of Honor the Earth, has famously stated, "We are in the midst of a climate crisis, and the first place that we need to look for solutions is to Indigenous peoples."

Beyond resource conflicts, Turtle Island is grappling with the haunting legacy of residential schools – a system designed to assimilate Indigenous children by stripping them of their language, culture, and family ties. The discovery of thousands of unmarked graves at former residential school sites across Canada since May 2021 has sent shockwaves globally, forcing a long-overdue public reckoning with this dark chapter. These discoveries, often confirmed through ground-penetrating radar, are not merely historical footnotes; they are ongoing trauma for survivors and their descendants, profoundly impacting health, social cohesion, and trust in institutions.

The Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation’s announcement of 215 probable unmarked graves at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School ignited a continent-wide search and a cascade of similar findings at institutions operated by various churches and the Canadian government. These revelations led to a historic apology from Pope Francis in July 2022 on Canadian soil, acknowledging the Church’s role in the "deplorable" system. However, for many survivors and Indigenous leaders, apologies are only a first step. Calls for genuine reparations, the return of land, the release of residential school records, and accountability for those who committed abuses continue to mount. This ongoing process of truth and reconciliation (or lack thereof) is a defining current event, revealing the deep structural racism embedded within colonial states and the immense resilience of those who survived and are fighting for justice.

Another pervasive crisis on Turtle Island is the epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit People (MMIWG2S). This is not just a Canadian issue but a continental one, with alarming rates of violence and disappearance affecting Indigenous individuals in both Canada and the United States. Systemic factors, including colonialism, racism, poverty, and intergenerational trauma, contribute to this vulnerability. The Canadian National Inquiry into MMIWG2S, which concluded in 2019, unequivocally declared the situation a "genocide" and issued 231 Calls for Justice. Yet, progress on implementing these calls has been slow, and the violence persists.

In the U.S., similar efforts are underway, with federal initiatives like Savanna’s Act and Not Invisible Act aiming to improve data collection and coordination between jurisdictions. However, communities continue to mourn and organize, often pointing to the connection between resource extraction "man camps" and increased rates of sexual assault and violence against Indigenous women. The MMIWG2S crisis is a stark reminder of the devaluation of Indigenous lives and the urgent need for systemic change, protection, and justice. Indigenous women and Two-Spirit people are leading this movement, demanding that their relatives be found, remembered, and protected.

Amidst these profound challenges, Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island are also at the forefront of innovative solutions and powerful cultural resurgence. As climate change accelerates, Indigenous communities, often the first and most severely impacted by extreme weather events, are also leading the charge in developing sustainable practices rooted in traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). From managed forest fires to protect against mega-blazes in California, to regenerative agriculture practices, and the protection of biodiversity, Indigenous perspectives offer critical pathways for addressing the global environmental crisis.

The "Land Back" movement is gaining significant traction, advocating for the return of Indigenous lands and resources, not just for symbolic reasons but as a fundamental step towards true self-determination and environmental stewardship. This movement recognizes that Indigenous land tenure often leads to better conservation outcomes, as Indigenous communities have historically managed their territories with a long-term, intergenerational perspective.

Furthermore, there is a powerful revitalization of Indigenous languages, arts, and governance structures. Language immersion schools are emerging across the continent, working to reverse generations of forced assimilation and ensure the continuity of ancestral tongues like Anishinaabemowin, Cree, Mohawk, and Lakota. Artists are using traditional and contemporary mediums to tell their stories, challenge stereotypes, and celebrate their cultures. Nations are asserting greater control over their health, education, and justice systems, building institutions that reflect their values and meet the unique needs of their communities. The rise of Indigenous-led economic development initiatives, from renewable energy projects to tourism, also demonstrates a pathway to self-sufficiency and the creation of thriving communities on their own terms.

In conclusion, Turtle Island is a continent in constant motion, a testament to the enduring spirit of its original inhabitants. The current events unfolding across its vast landscapes are not isolated incidents but interconnected facets of a long-standing struggle against colonialism and for self-determination. From the front lines of pipeline protests and the painful search for unmarked graves, to the vital work of language revitalization and climate leadership, Indigenous peoples are asserting their sovereignty, reclaiming their narratives, and charting a future rooted in justice, respect, and balance. To truly understand the present and future of North America, one must listen intently to the unyielding pulse of Turtle Island and the voices of those who have always called it home. Their struggles are our collective responsibility, and their resurgence offers profound lessons for humanity.