Coushatta Pine Needle Basketry: Preserving a Delicate Tribal Art Form

In the quiet heart of Louisiana, amidst the rustling longleaf pines, lies a cultural treasure meticulously woven by the hands of the Coushatta (Koasati) people: pine needle basketry. Far more than a mere craft, this intricate art form embodies centuries of tradition, spiritual connection to the land, and the enduring resilience of a tribal community. Yet, like many indigenous art forms, it faces the relentless pressures of modernization, threatening to unravel a delicate heritage that has been passed down through generations.

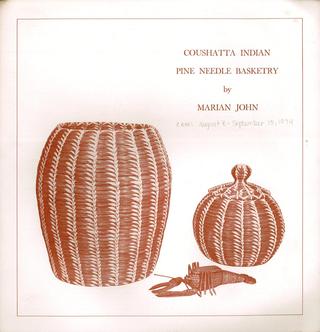

Coushatta pine needle basketry is immediately recognizable for its distinctive aesthetic – tightly coiled, often vibrant, and imbued with an organic beauty that speaks of the forests from which its primary material is sourced. Unlike many other basketry traditions that utilize reeds, grasses, or splints, the Coushatta employ the long, supple needles of the longleaf pine (Pinus palustris). These needles, gathered with respect and careful selection, form the foundation of each piece, coiled and stitched together with a fine thread, often colorful raffia, creating durable and visually stunning vessels. The technique itself is a testament to patience and skill: bundles of dried pine needles are progressively coiled into the desired shape, each coil meticulously stitched to the previous one using a bone or metal awl to pierce the tightly bound needles. The result is a remarkably sturdy, aromatic, and often waterproof basket, ranging from small, decorative trinket holders to large, utilitarian storage containers.

The art form is steeped in the rhythms of nature and the wisdom of elders. Basket makers must possess an intimate understanding of their environment, knowing precisely when and where to gather the longest, most pliable needles – typically those that have fallen naturally from the tree, rich in their natural oils and flexibility. This practice alone connects the artisan directly to the ecosystem, fostering a reciprocal relationship of respect and stewardship. The selection of materials extends beyond the pine needles; sweetgrass (Hierochloe odorata), though less common in pure Coushatta pine needle work, is sometimes incorporated for its aromatic qualities and contrasting texture, while natural dyes or brightly colored threads are used to introduce intricate patterns and designs, transforming functional objects into expressions of profound artistic vision. Each basket tells a story, often reflecting natural elements, geometric patterns passed down through families, or the individual creativity of the weaver.

For the Coushatta, pine needle basketry is not merely an economic activity or a hobby; it is a living conduit to their ancestral past and a powerful affirmation of their cultural identity. Historically, baskets served essential roles in daily life – for gathering, storage, and food preparation. They were practical tools, but always imbued with aesthetic value. More significantly, the creation of baskets has long been a communal and intergenerational practice, primarily among women, fostering bonds and ensuring the transmission of knowledge, stories, and cultural values. An elder teaching a younger relative to weave is not just imparting a technical skill; she is sharing history, language, and a worldview that emphasizes patience, precision, and harmony with nature. This oral tradition, passed from hand to hand and heart to heart, is the very essence of the art form’s survival.

However, the delicate threads of this tradition are under increasing strain. The most significant challenge lies in the loss of knowledge transmission. With fewer young people choosing to dedicate the immense time and effort required to master the craft, the pool of skilled artisans shrinks with each passing generation. The intricate techniques and subtle nuances, once widely understood, risk being forgotten as elders pass on without apprentices to carry their knowledge forward. "It’s a slow art," remarks one Coushatta elder, emphasizing the commitment. "You have to be patient. You have to love it. And our young ones, they have so many other things pulling their attention."

Another critical hurdle is material sourcing. The longleaf pine ecosystem, once dominant across the southeastern United States, has been drastically reduced due to logging, agriculture, and urban development. While efforts are being made to restore these vital forests, finding consistent access to high-quality, long needles suitable for basketry remains a concern. The quality of needles can be affected by environmental factors, climate change, and even controlled burns, which, while beneficial for forest health, can singe the fallen needles, rendering them unusable. This dependency on a specific natural resource makes the art form vulnerable to environmental degradation and land-use changes.

Economic viability also presents a formidable challenge. A single, intricately woven pine needle basket can take hundreds of hours to complete, demanding meticulous attention and highly refined skills. In a market dominated by mass-produced goods, valuing these handmade masterpieces appropriately is difficult. Artisans often struggle to command prices that adequately compensate for their time, skill, and the cultural significance embedded in each piece. This economic pressure can deter potential new weavers, pushing them towards more financially lucrative modern professions.

Despite these formidable obstacles, the Coushatta people, along with dedicated cultural organizations and individuals, are actively engaged in powerful preservation efforts. The Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana has established cultural programs and centers dedicated to teaching traditional arts, including basketry. Workshops are regularly held, inviting tribal members of all ages to learn from master weavers. These initiatives are not just about teaching technique; they are about fostering a sense of cultural pride and continuity, ensuring that the next generation understands the profound value of their heritage.

Master-apprentice programs are proving particularly effective, pairing experienced artisans with aspiring weavers in intensive, long-term learning relationships. These programs not only transfer technical skills but also the oral histories, songs, and spiritual understandings associated with the craft. "When I teach," says a master weaver, "I’m not just showing them how to stitch. I’m telling them stories of our grandmothers, of our land, of why this is important to us."

Beyond internal tribal efforts, partnerships with museums, cultural institutions, and universities play a crucial role. Documentation of basketry techniques, oral histories of artisans, and archival collections help to preserve knowledge for future generations, even if the direct transmission line falters. These institutions also provide platforms for exhibiting and selling Coushatta basketry, raising public awareness and creating a wider market for these unique works of art, which can help support the artisans financially. Ethical commercialization, through tribal enterprises and reputable galleries, allows the art form to sustain itself while educating the public about its cultural significance and the skill involved.

The future of Coushatta pine needle basketry is a delicate balance, woven between tradition and adaptation, preservation and innovation. It hinges on the continued dedication of the Coushatta people to their heritage, the success of ecological efforts to preserve the longleaf pine forests, and the ongoing support from a wider audience who appreciate the beauty, skill, and cultural depth of this extraordinary art form. Each basket, with its fragrant coils and intricate patterns, is more than just an object; it is a testament to the enduring spirit of the Coushatta, a prayer for continuity, and a living, breathing connection to a rich and vibrant past. To preserve Coushatta pine needle basketry is not merely to save an art form; it is to safeguard a vital piece of human history, creativity, and cultural identity.