Guardians of the Grand Coulee: The Enduring Legacy of the Colville Confederated Tribes

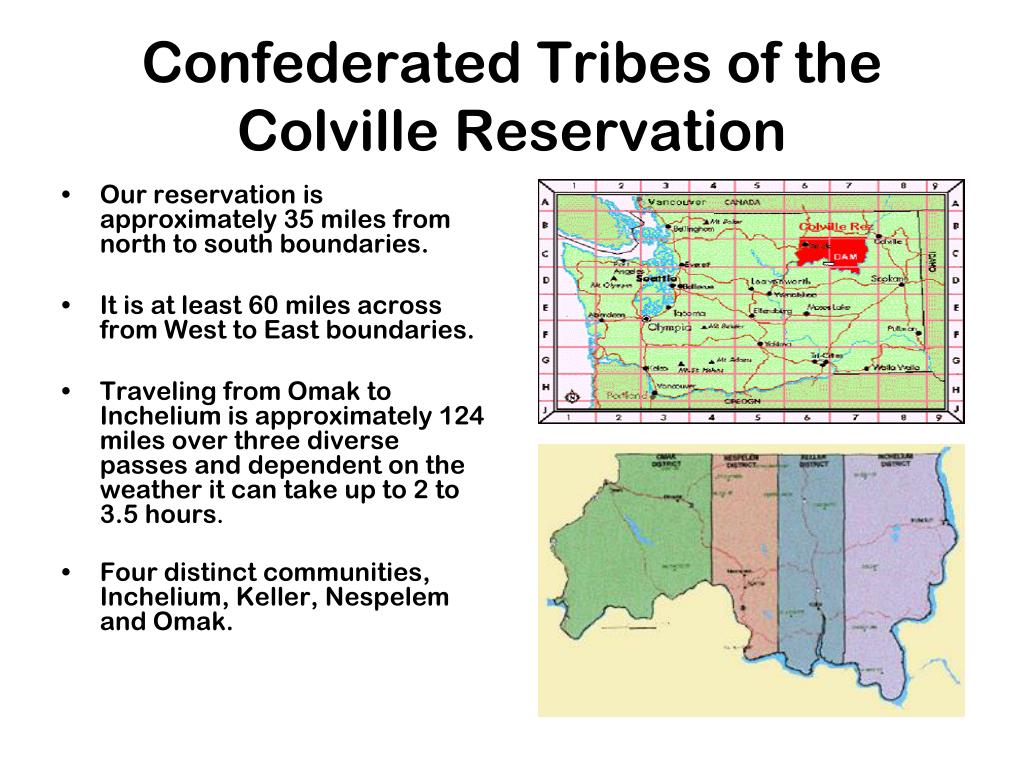

NESPELEM, Washington – From the ancient, life-giving waters of the Columbia River to the rugged, pine-studded mountains that define its horizons, the land of the Colville Confederated Tribes is steeped in history, resilience, and an unwavering connection to ancestral ways. Spanning 1.4 million acres in north-central Washington, this diverse confederation represents twelve distinct tribes, each with its own rich heritage, yet bound by a shared past of profound disruption and an enduring future forged through unity and self-determination.

To understand the Colville Confederated Tribes is to embark on a journey through millennia of sophisticated Indigenous civilization, through the seismic shifts brought by European contact, the painful crucible of land dispossession and assimilation, and finally, to a vibrant present where cultural revitalization and economic sovereignty are paramount.

A Tapestry of Ancient Cultures

Before the arrival of European explorers and settlers, the territories now comprising the Colville Reservation and surrounding lands were home to a vibrant array of interconnected Indigenous nations. These included the Colville, Nespelem, Sanpoil, Lakes (Sinixt), Okanogan, Methow, Wenatchi, Entiat, Chelan, Palus, and the Chief Joseph Band of Nez Perce, along with the Moses-Columbia people. Each tribe maintained unique languages, customs, and spiritual practices, yet shared a deep reverence for the land and its resources.

Life revolved around the seasonal bounty of the Columbia River and its tributaries, as well as the vast inland territories. Salmon, the "sacred fish," was the dietary and spiritual cornerstone, its annual return celebrated with intricate ceremonies and sophisticated fishing techniques. Root vegetables like camas and bitterroot, along with berries and game, completed a diet that sustained these communities for thousands of years. Trade networks, extending from the Pacific Coast to the Great Plains, facilitated the exchange of goods, knowledge, and culture, demonstrating a highly organized and interconnected society.

"Our ancestors lived by the river, their lives intertwined with the salmon," explains Lena Williams, a Nespelem elder and language instructor. "Kettle Falls, just north of the present-day reservation, was a spiritual heartland, a gathering place for tribes from all directions. It was a place of abundance, ceremony, and peace."

The Tides of Change: Contact and Dispossession

The late 18th and early 19th centuries marked the beginning of an irreversible transformation. Fur traders, primarily from the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company, were the first sustained European presence. While initially fostering trade, their arrival brought devastating diseases like smallpox, which decimated Indigenous populations lacking immunity. Missionaries followed, introducing Christianity and challenging traditional spiritual beliefs.

By the mid-19th century, the relentless westward expansion of American settlers intensified pressure on tribal lands. Unlike many tribes in the Pacific Northwest, the Colville Confederated Tribes were unique in that a singular, comprehensive treaty was never signed with the U.S. government. Instead, their reservation was established through a series of executive orders, beginning with President Ulysses S. Grant in 1872. This initial reservation was vast, encompassing some 2.85 million acres.

However, this period was characterized by a rapid and devastating contraction of tribal lands. Within a few short years, the reservation was drastically reduced. The 1878 Moses Agreement and subsequent cessions in 1891 and the early 1900s stripped the tribes of vast portions of their ancestral territory, opening it up for non-Native settlement and resource extraction. The Dawes Act of 1887 further fragmented communal landholdings into individual allotments, a federal policy designed to break tribal unity and encourage assimilation.

Perhaps one of the most poignant narratives of this era involves the Chief Joseph Band of Nez Perce. After their heroic, yet ultimately unsuccessful, flight from U.S. troops in 1877, they were initially exiled to Oklahoma. In 1885, a portion of the band, including Chief Joseph, was allowed to return to the Pacific Northwest, but were settled on the Colville Reservation, far from their Wallowa Valley homeland, joining a confederation already grappling with its own struggles. This act, while a testament to the resilience of the Nez Perce, also underscored the arbitrary nature of federal Indian policy.

The Grand Coulee Dam: A River Silenced

No single event symbolizes the profound loss and sacrifice endured by the Colville Confederated Tribes more than the construction of the Grand Coulee Dam in the 1930s. A monumental engineering feat aimed at providing irrigation and hydroelectric power to the region, the dam was built without fish ladders, effectively blocking the upstream migration of salmon, forever severing a vital cultural, economic, and spiritual lifeline.

The dam flooded ancestral fishing sites, burial grounds, and fertile agricultural lands. Kettle Falls, the sacred gathering place for centuries, was submerged beneath the dam’s massive reservoir, Lake Roosevelt. The impact was catastrophic. "When the dam was built, it wasn’t just a river that was dammed; it was a way of life, a spiritual connection that was broken," says Richard Tonasket, a tribal historian. "The salmon sustained us, spiritually and physically. That loss reverberates through generations."

The federal government acquired tribal lands for the dam project, but initial compensation was meager and belated. It took decades of persistent advocacy for the tribes to receive any significant recognition or restitution for the immense sacrifices made for national development. This struggle for environmental justice and fair compensation continues to this day, with ongoing efforts to restore salmon runs and heal the Columbia River ecosystem.

The Dawn of Self-Determination and Renewal

Despite these profound challenges, the Colville Confederated Tribes never surrendered their identity or their inherent sovereignty. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 provided a critical opportunity for tribes to re-establish self-governance. In 1938, the tribes adopted a constitution and formed a tribal council, laying the groundwork for modern tribal government and asserting their right to self-determination.

The latter half of the 20th century saw a resurgence of cultural pride and a renewed push for economic independence. The tribal government, operating with a sophisticated administrative structure, began to reclaim control over their resources and destiny. Forestry, traditionally a major industry, was revitalized under tribal management, ensuring sustainable practices and providing vital employment.

Today, the Colville Confederated Tribes are a powerful economic and cultural force in north-central Washington. They are the largest employer in Okanogan County, with diverse enterprises ranging from timber and agricultural operations to gaming (Colville Casinos) and tourism. These ventures not only provide essential services and jobs for tribal members but also contribute significantly to the broader regional economy.

Preserving Culture, Building the Future

Cultural revitalization is at the heart of the Colville narrative. Programs dedicated to language immersion are striving to revive endangered tribal languages like Nespelem Salish and Colville-Okanogan, ensuring that the wisdom and stories of elders are passed to younger generations. Traditional arts, crafts, dances, and ceremonies are once again flourishing, celebrated in community gatherings and educational initiatives.

"Language is the vessel of our culture, our worldview," states Williams. "To speak our language is to connect directly with our ancestors, to understand the world as they did."

The tribes are also at the forefront of environmental stewardship, working tirelessly to restore the health of their lands and waters. Efforts to reintroduce salmon to the upper Columbia River above Grand Coulee Dam, though complex and challenging, represent a powerful commitment to healing historical wounds and restoring ecological balance.

However, challenges remain. Like many Indigenous communities, the Colville Confederated Tribes grapple with the lingering effects of historical trauma, including issues such as poverty, substance abuse, and inadequate healthcare and educational resources. Yet, the spirit of resilience and community remains strong.

The Colville Confederated Tribes stand as a testament to the enduring strength of Indigenous peoples. Their history is a powerful narrative of survival, adaptation, and an unwavering commitment to cultural heritage. From the ancient fishing grounds of Kettle Falls to the modern halls of tribal government, the Colville people continue to be the guardians of their land, their culture, and their future, charting a course for self-sufficiency and sovereignty that honors their past while boldly embracing the opportunities of tomorrow. Their story is a vital chapter in the broader American narrative, a reminder of the profound contributions and ongoing struggles of Indigenous nations.