More Than Blood: The Enduring Saga of Cherokee Nation Tribal Enrollment in Oklahoma

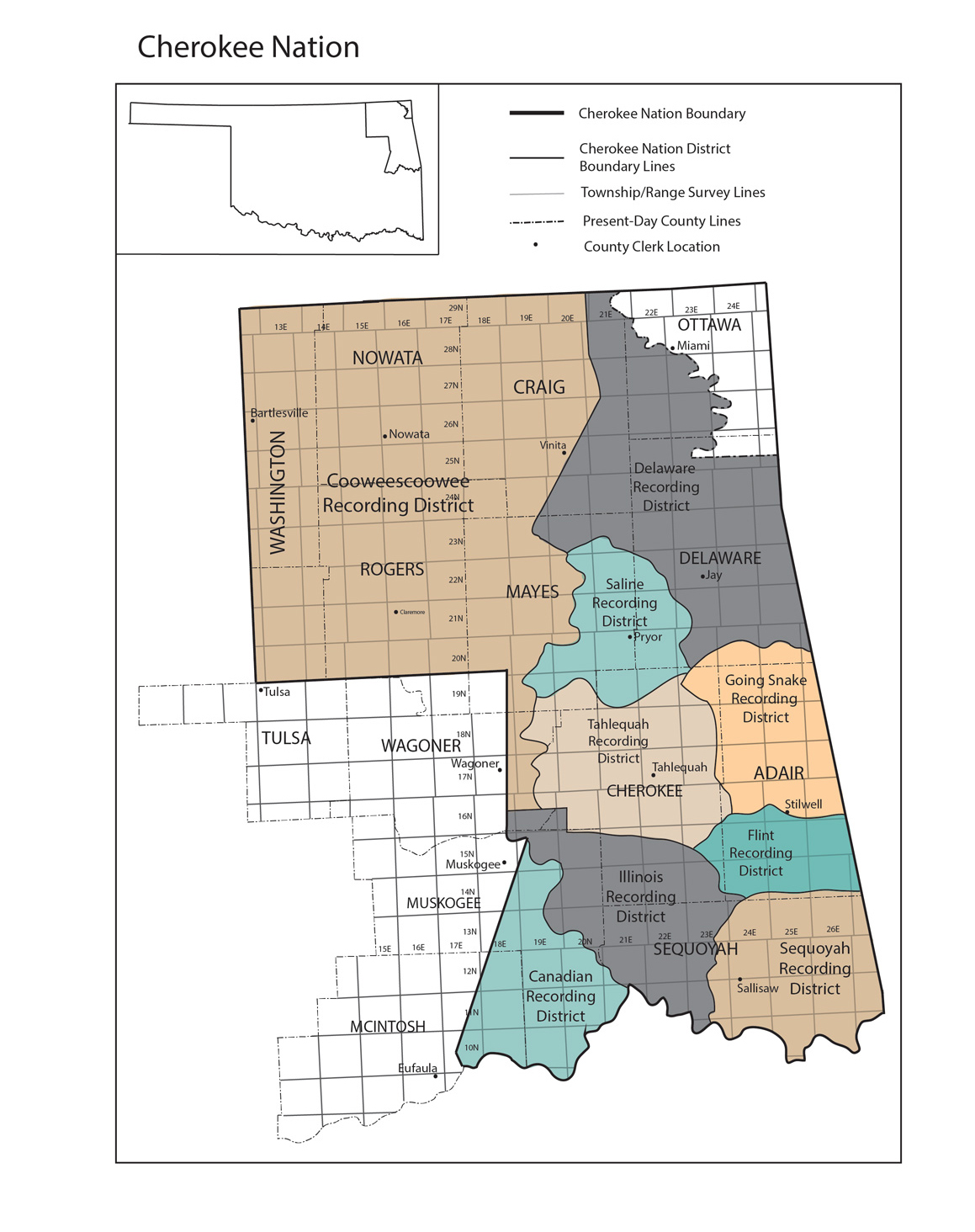

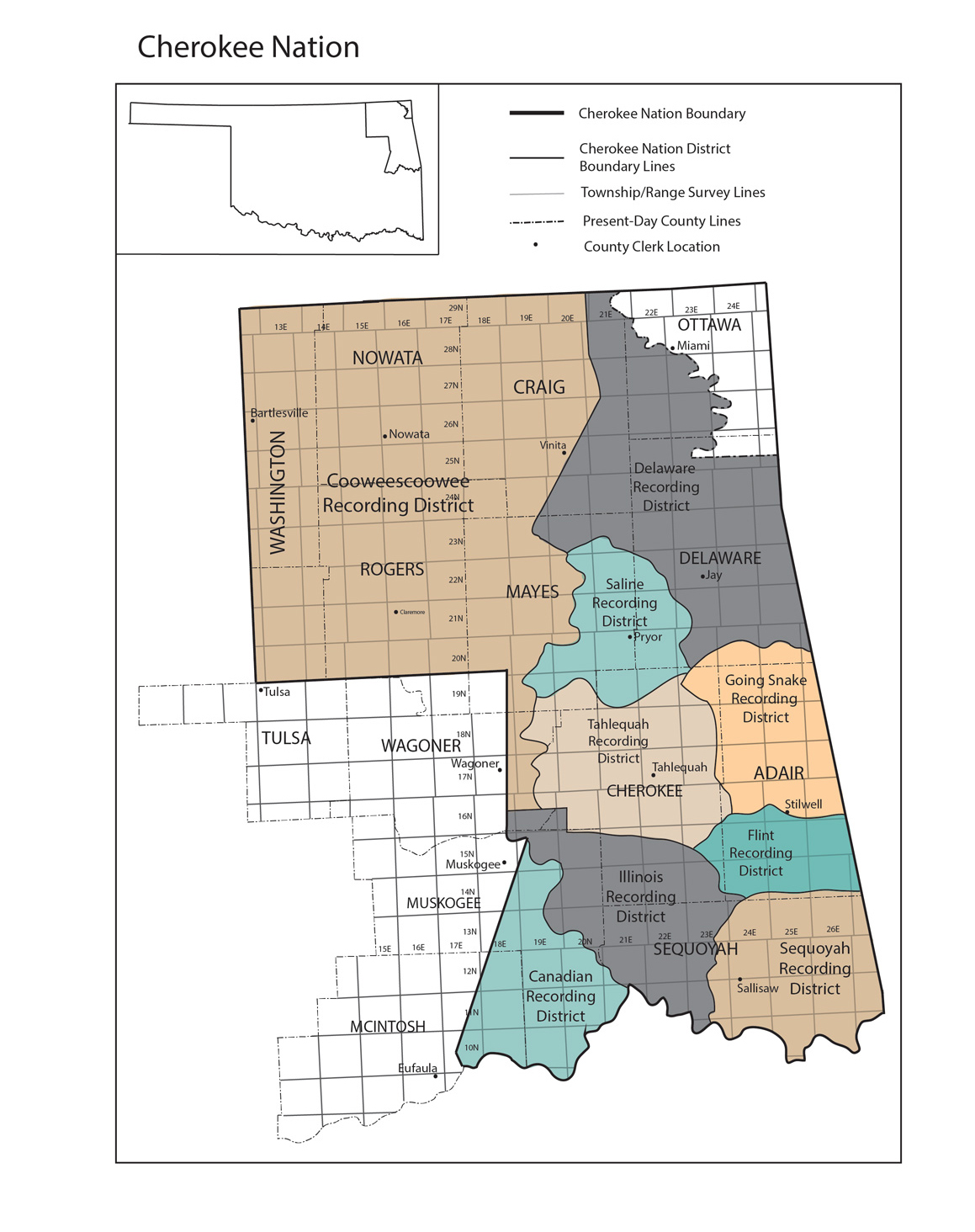

TAHLEQUAH, Oklahoma – In the rolling hills and verdant valleys of northeastern Oklahoma, where the Cherokee Nation’s influence stretches far beyond its physical boundaries, a profound process of identity, history, and sovereignty unfolds daily: tribal enrollment. For many, it’s a journey back through generations, a connection to a past marked by both immense suffering and indomitable resilience. For the Cherokee Nation itself, it is the bedrock of its existence, defining its people, its power, and its future.

With over 450,000 citizens, the Cherokee Nation stands as the largest federally recognized tribe in the United States. Its story is one of forced removal, adaptation, and an enduring commitment to self-governance. Central to this narrative is the intricate and often emotionally charged process of becoming an enrolled citizen – a process that intertwines the legacy of a devastating past with the vibrant aspirations of a modern sovereign nation.

The Echoes of the Trail of Tears and the Dawes Rolls

To understand Cherokee Nation enrollment today, one must first look back. The 19th century brought unimaginable hardship to the Cherokee people. Despite adopting a written language, a constitution, and a farming lifestyle, they faced relentless pressure from the U.S. government and land-hungry settlers. This culminated in the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the subsequent forced march known as the Trail of Tears (Nunna daul Isunyi in Cherokee), where over 4,000 of the 16,000 Cherokees died during their removal from their ancestral lands in the Southeast to Indian Territory, present-day Oklahoma.

Barely a generation after rebuilding, another existential threat emerged: the Dawes Act of 1887 and the subsequent creation of the Dawes Rolls. This federal initiative aimed to break up tribal landholdings into individual allotments, dissolve tribal governments, and assimilate Native Americans into mainstream American society. From 1899 to 1907, federal agents compiled lists of individuals deemed eligible for land allotments, known as the Dawes Rolls or the "Final Rolls of Citizens and Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes."

"The Dawes Rolls are a double-edged sword," explains Dr. Daniel Heath Justice, a Cherokee Nation citizen and professor of First Nations and Indigenous Studies at the University of British Columbia. "They were a tool of dispossession, designed to dismantle our nationhood. Yet, paradoxically, they became the foundational document for modern tribal citizenship, a necessary evil we had to adapt to in order to maintain a recognized political body."

Today, the primary requirement for Cherokee Nation citizenship is lineal descent from an individual listed on the Dawes Rolls as a "Cherokee by Blood." Unlike many other tribes, the Cherokee Nation does not impose a minimum blood quantum – a measure of the percentage of Native American ancestry – for enrollment. This distinction is crucial, as it emphasizes political lineage and historical connection over biological purity, a concept often imposed by colonial powers.

The Mechanics of Enrollment: Tracing the Lineage

For an aspiring citizen, the journey begins with meticulous genealogical research. Applicants must submit official documentation – birth certificates, marriage licenses, death certificates – to trace their direct lineage back to a Dawes Roll enrollee. This can be a challenging endeavor, as historical records can be incomplete, inaccurate, or difficult to obtain.

"It’s like being a detective for your own family," says Sarah Littlebear, a 34-year-old Cherokee Nation citizen who spent months compiling her documentation. "I knew my grandmother was Cherokee, but proving the paper trail back to my ancestor on the Dawes Roll, finding those specific entries, took a lot of work. But every piece of paper I found felt like connecting another thread to who I am."

The Cherokee Nation’s Tribal Registration Department assists applicants, providing resources and guidance. Once the lineage is verified, a Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood (CDIB) card is issued, followed by a tribal citizenship card. This card is more than just identification; it is a tangible link to a rich heritage and a living community.

The Freedmen Controversy: A Defining Chapter

No discussion of Cherokee Nation enrollment would be complete without acknowledging the profound and often painful history of the Cherokee Freedmen. These are the descendants of enslaved African Americans who were owned by some Cherokee citizens prior to the Civil War. In the aftermath of the war, the 1866 Treaty between the Cherokee Nation and the United States stipulated that the Freedmen and their descendants "shall have all the rights of native Cherokees."

Despite this treaty, the Cherokee Nation largely denied full citizenship rights to Freedmen descendants for decades, leading to a protracted legal battle. The Nation argued that tribal sovereignty allowed it to define its own citizenry, while Freedmen descendants pointed to the explicit language of the 1866 treaty.

In a landmark decision in 2017, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia ruled that the Cherokee Nation must recognize the Freedmen descendants as full citizens, a decision upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court’s refusal to hear the Nation’s appeal. This ruling effectively ended the long-standing dispute, adding thousands of new citizens to the Cherokee Nation.

Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. reflected on the resolution in a statement: "It was a painful chapter, and the legal battle was certainly a test of our sovereignty. But ultimately, we are a nation of laws, and we are committed to justice and our treaty obligations. Welcoming the Freedmen descendants as full citizens has made our Nation stronger and more representative of our complex history."

The integration of the Freedmen descendants was a testament to the Cherokee Nation’s resilience and its ability to confront its own history, reinforcing the idea that citizenship is rooted in historical treaties and political affiliation, not solely on "blood" as defined by external forces.

Why Enrollment Matters: Identity, Sovereignty, and Services

For individual citizens, enrollment is profoundly personal. It’s a formal acknowledgment of identity, a connection to a distinct culture, language, and worldview. It opens doors to participating in cultural revitalization efforts, learning the Cherokee language (Tsalagi), and engaging in community life.

"It’s about belonging," says Michael Snake, a community elder and cultural preservationist. "Knowing you are officially part of the Cherokee Nation gives you a sense of rootedness, a place in the world that no one can take away. It connects you to those who came before you and obligates you to those who will come after."

Beyond individual identity, enrollment is fundamental to the Cherokee Nation’s sovereignty and its ability to provide for its people. Federal funding for tribal programs – including healthcare, education, housing, and infrastructure – is often tied to enrollment numbers. A larger citizenry translates into greater federal resources, bolstering the Nation’s capacity to serve its people.

The Cherokee Nation operates its own extensive healthcare system, including the largest tribal health care facility in the country, the Cherokee Nation Health Services W.W. Hastings Hospital in Tahlequah. It also offers scholarships, housing assistance, language immersion programs, and robust cultural initiatives, all primarily for its enrolled citizens. The economic impact of the Nation, driven by diverse enterprises including gaming, hospitality, and manufacturing, directly benefits its citizens through these comprehensive services and programs.

The Future: Growth and Continued Challenges

The Cherokee Nation continues to grow, with thousands of new citizens enrolling each year. This growth presents both opportunities and challenges. It signifies a vibrant and engaged population, eager to connect with their heritage and contribute to the Nation’s future. It also places increasing demands on tribal resources and infrastructure.

As the Cherokee Nation looks to the future, the conversation around enrollment will continue to evolve. Discussions around historical accuracy of the Dawes Rolls, the complexities of identity in a globalized world, and the ongoing balance between tradition and modernity are constant.

"Our citizenship is the bedrock of our sovereignty. It’s how we define ourselves, how we govern, and how we ensure our future," states Principal Chief Hoskin Jr. "Every new citizen strengthens our voice and our capacity to advocate for our people and protect our inherent rights."

In Oklahoma, where the memory of forced removal lingers in the landscape, the process of Cherokee Nation tribal enrollment is far more than a bureaucratic formality. It is a powerful act of reclaiming identity, honoring ancestors, and asserting the enduring strength of a sovereign people. It is a testament to the fact that even after generations of federal attempts to erase them, the threads of Cherokee identity continue to be woven, stronger and more vibrant than ever.