The Enduring Heartbeat: Cherokee Nation and the Sacred Landscape of Turtle Island

In the sprawling tapestry of North America, a continent many Indigenous peoples know as Turtle Island, the ancestral lands of the Cherokee Nation resonate with a profound, enduring heartbeat. For millennia, these lands, stretching across what is now the southeastern United States, have been more than mere territory; they are the cradle of a civilization, the wellspring of culture, language, and identity for the Tsalagi, or Cherokee people. This deep, spiritual connection to the land – a concept intrinsically linked to the Turtle Island worldview – has shaped their history, defined their resilience, and continues to guide their path forward, even in the face of immense historical trauma and displacement.

The concept of Turtle Island itself is a foundational Indigenous creation narrative shared by many nations across North America. It speaks of a vast ocean and a benevolent spirit, often a muskrat or a turtle, bringing earth from the depths to form the land. For the Cherokee, this narrative imbues the land with a sacred essence, making it a living entity, a mother from whom all life springs. This worldview fostered a deep reverence for the natural world, a commitment to stewardship, and a reciprocal relationship where the land sustained the people, and the people, in turn, cared for the land.

Before European contact, the ancestral Cherokee domain encompassed a vast, fertile region spanning parts of modern-day Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, Kentucky, and West Virginia. This was a land of rolling mountains – the Blue Ridge and the Great Smoky Mountains – abundant rivers like the Tennessee, Little Tennessee, and Hiwassee, and diverse ecosystems that provided sustenance and spiritual grounding. The Cherokee cultivated sophisticated agricultural systems, growing corn, beans, and squash, and lived in well-organized towns with advanced governance structures, including a sophisticated legal system and a representative council. Their society was matriarchal, with women holding significant power and influence, particularly in matters of land and agriculture.

The arrival of European settlers marked a cataclysmic shift. Driven by insatiable land hunger and the allure of resources, a relentless campaign of encroachment began. Treaties, often signed under duress or with unrepresentative factions, were systematically broken. The Cherokee, adapting to the changing world, adopted aspects of American culture, developing a written language (the syllabary created by Sequoyah in 1821, which made literacy widespread), establishing a constitutional government, and even owning plantations. They sought to integrate and demonstrate their capacity for "civilization," hoping to secure their lands through legal means.

However, the discovery of gold in Georgia in 1828 ignited a feverish desire for Cherokee lands, leading to one of the darkest chapters in American history: the forced removal. Despite a landmark Supreme Court victory in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), which affirmed Cherokee sovereignty and invalidated Georgia’s claims, President Andrew Jackson famously defied the ruling, stating, "John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it."

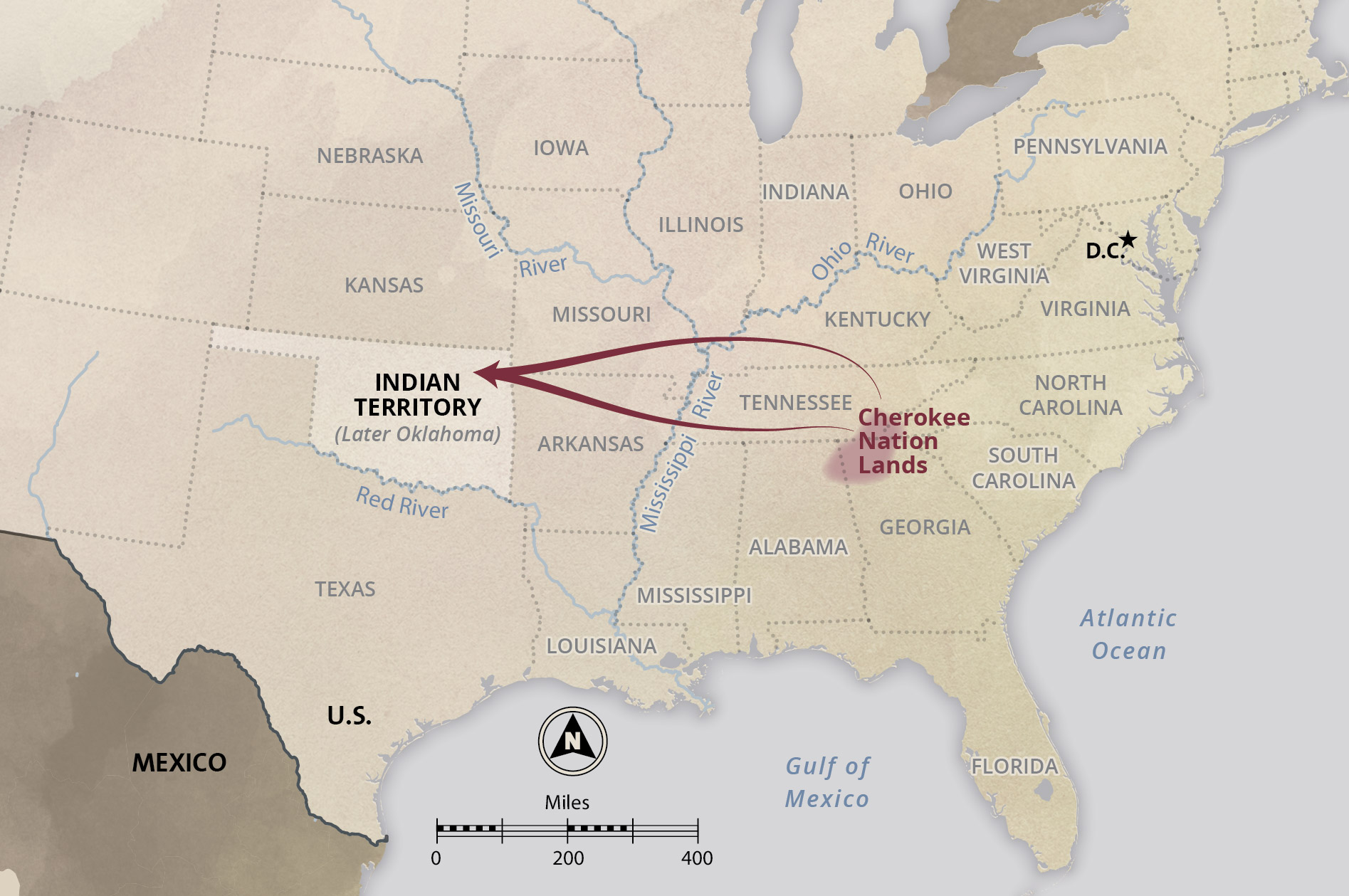

This defiance culminated in the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the subsequent forced relocation of the Cherokee and other Southeastern Indigenous nations. From 1838 to 1839, approximately 16,000 Cherokee people were forcibly marched over 1,000 miles from their ancestral homes to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). This brutal journey, infamously known as the Trail of Tears, resulted in the deaths of over 4,000 Cherokee men, women, and children from disease, starvation, and exposure. Their profound connection to their ancestral lands made the removal an unimaginable spiritual and cultural devastation. As Chief John Ross wrote, "The Cherokee people are a people of the soil, they have their homes, their fields, their orchards, their churches, their schools, their graves. To be torn from these, to be driven to a distant and strange land, is a thought too agonizing to dwell upon."

Yet, the story of the Cherokee is not solely one of tragedy; it is profoundly one of resilience. A small group of Cherokee managed to evade removal, either by hiding in the remote mountains of North Carolina or by making special arrangements, forming the nucleus of what is now the federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI). These descendants continue to live on a portion of their ancestral lands, primarily the Qualla Boundary in western North Carolina, a testament to their unwavering connection to place.

Miles away, in Indian Territory, the forcibly removed Cherokee Nation rebuilt. They re-established their government, schools, and communities, demonstrating an extraordinary capacity for self-governance and cultural preservation. Despite the geographical separation, the memory of their ancestral lands, the stories of the rivers and mountains, and the spiritual connection to Turtle Island remained vibrant. Elders passed down oral histories, ceremonies continued, and the language, though challenged, persisted as a vital link to their heritage.

Today, both the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma (the largest federally recognized tribe in the United States, with over 450,000 citizens) and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians are thriving, sovereign nations. Their connection to ancestral lands, both those they inhabit and those from which they were removed, remains central to their identity and their political actions.

For the Eastern Band, the Qualla Boundary is a living embodiment of their ancestral connection. They actively manage and protect their environment, incorporating traditional ecological knowledge into modern conservation efforts. Their cultural preservation initiatives, including language immersion programs and traditional arts, are deeply rooted in the context of their mountain homeland. Their museum, the Oconaluftee Indian Village, and cultural events serve as powerful reminders and educational tools about their enduring presence and rich heritage.

For the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma, while geographically distant from their original homelands, the concept of ancestral lands on Turtle Island remains a powerful force. This connection manifests in various ways:

- Cultural Reclamation: Efforts to revive traditional ceremonies, dances, and agricultural practices often draw inspiration from the pre-removal ways of life tied to their original landscape.

- Language Revitalization: The Cherokee language, or Tsalagi, is intimately tied to the land, with place names and descriptive terms reflecting the features of their ancestral territory. Revitalizing the language is, in part, a way of reconnecting to that deeper geographical and spiritual understanding.

- Environmental Stewardship: The Cherokee Nation actively engages in environmental protection and sustainability initiatives within Oklahoma, often guided by the same principles of reciprocal care for the land that characterized their relationship with their ancestral homelands.

- Historical Memory: The Trail of Tears is not just a historical event but a living memory that informs their present. The desire to honor their ancestors and ensure that such injustices are never repeated is a powerful motivator for sovereignty and self-determination.

- Advocacy and Education: The Cherokee Nation educates the public about their history, culture, and their ancestral lands, challenging misconceptions and asserting their inherent rights. They also engage in dialogues and partnerships with institutions and communities in the southeastern U.S. to ensure the respectful acknowledgment and protection of historic Cherokee sites.

A significant recent triumph for tribal sovereignty and land recognition came with the 2020 Supreme Court ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma. While not directly related to their ancestral lands in the Southeast, this decision affirmed that a large portion of eastern Oklahoma, encompassing much of the Cherokee Nation’s reservation boundaries, remains "Indian Country" for purposes of federal criminal law. This ruling, rooted in treaty rights, underscored the enduring legal and political reality of Indigenous nations within the United States, reinforcing the principle that their territories, even those established after forced removal, possess unique legal status. It was a powerful affirmation of the continuity of Indigenous land claims and sovereignty within the larger context of Turtle Island.

The Cherokee Nation’s story, interwoven with the concept of Turtle Island and the memory of their ancestral lands, is a testament to the enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples. It is a narrative of profound loss, unimaginable suffering, but ultimately, one of unwavering resilience, cultural preservation, and the continuous fight for self-determination. Their relationship with the land transcends mere ownership; it is a spiritual bond, a living history, and a guiding principle for their future. As they navigate the complexities of the 21st century, the heartbeat of their ancestral lands, though distant for many, continues to echo, reminding them of who they are and the sacred responsibility they hold to the earth and to future generations. The land remembers, and so do the Cherokee.