Reclaiming California’s Wetlands: Indigenous Wisdom at the Forefront of Restoration

California’s wetlands, once vibrant arteries of life, have been systematically drained, paved, and polluted, leaving behind a fragmented shadow of their former glory. Over 90% of the state’s historical wetlands have been lost, a stark testament to centuries of colonial land use practices that prioritized development over ecological balance. Yet, a powerful counter-narrative is emerging, rooted in millennia of deep ecological knowledge: California’s Indigenous communities are not merely advocating for wetland protection, they are actively leading a profound resurgence in their restoration and management, demonstrating that true sustainability is inextricably linked to cultural revitalization and ancestral wisdom.

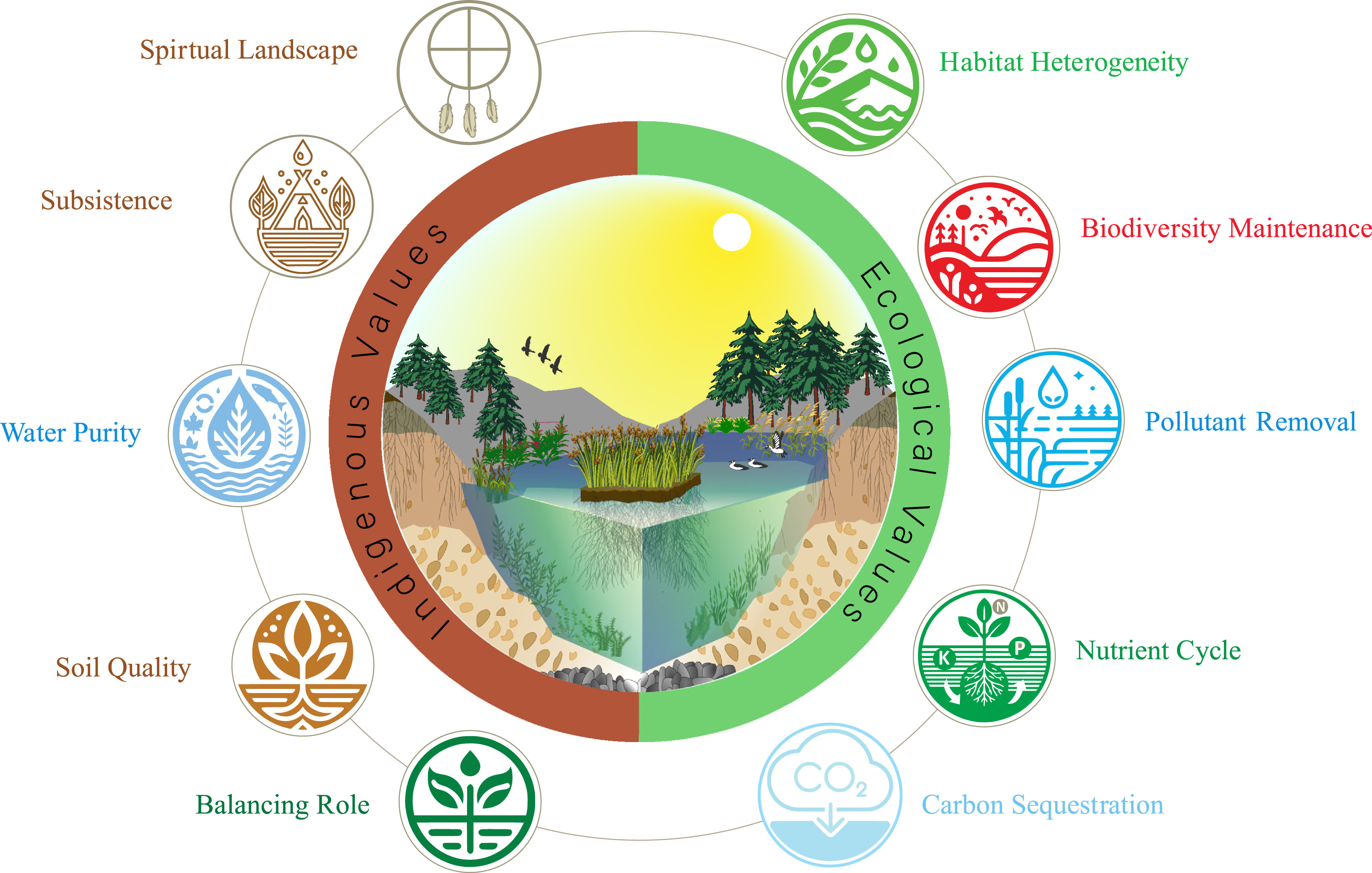

This is not a new science, but an ancient one, known as Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). For countless generations, Indigenous peoples across California meticulously managed their landscapes, including the vast and diverse wetland ecosystems that supported an unparalleled bounty of life. Their relationship with the land was, and remains, one of reciprocity and stewardship, where human actions are viewed as integral to the health of the entire ecosystem, not separate from it. Today, as climate change intensifies droughts, floods, and wildfires, and biodiversity collapses, the holistic, long-term perspective of Indigenous wetland resource management offers not just hope, but an essential blueprint for survival.

The modern Western approach to conservation often views nature as something to be protected from human intervention. In stark contrast, TEK recognizes that human interaction, when guided by deep understanding and respect, can be a vital force for ecological health. Indigenous peoples understood the dynamic nature of wetlands, utilizing practices like selective harvesting of tules and sedges for basketry, traditional fishing techniques that ensured species regeneration, and controlled cultural burns that cleared overgrown vegetation, recycled nutrients, and enhanced habitat diversity. These practices weren’t just about resource extraction; they were sophisticated forms of ecosystem engineering that fostered resilience and abundance.

The Historical Erasure and Its Consequences

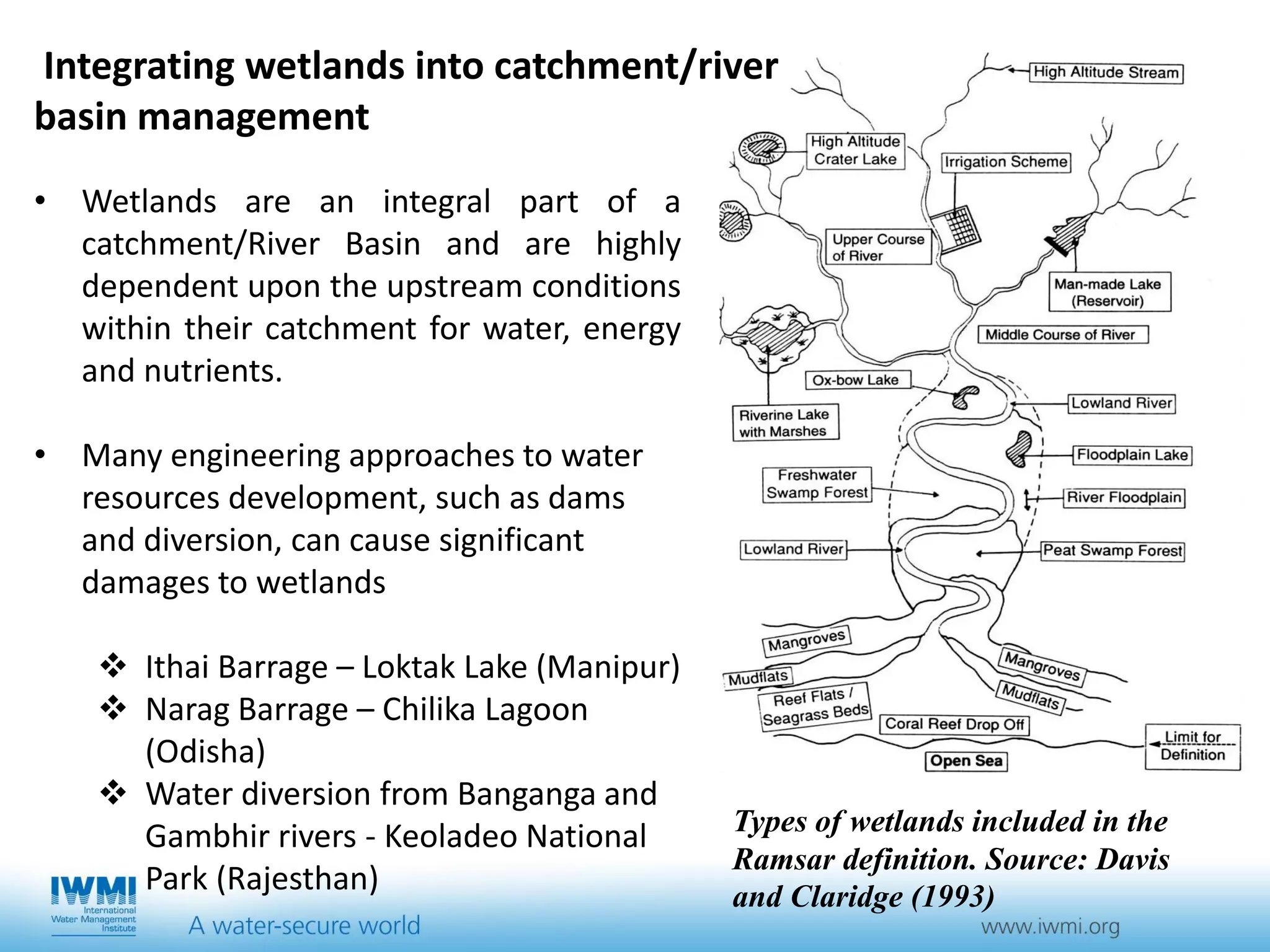

The arrival of European colonizers brought an abrupt and devastating end to these sustainable practices. Wetlands were seen as unproductive, disease-ridden lands ripe for conversion into agricultural fields, urban centers, and industrial sites. Dams fragmented rivers, cutting off vital water flows to downstream marshes. Fire suppression policies, imposed by federal and state agencies, led to a buildup of fuels, resulting in catastrophic megafires that now frequently consume even historically wet areas. Indigenous communities were dispossessed of their lands, their languages suppressed, and their traditional knowledge dismissed as primitive. The ecological consequences of this cultural and land-use shift have been catastrophic: endangered species lists grow longer, water quality plummets, and California faces an ever-increasing risk from climate-induced disasters.

But the knowledge persisted. Passed down through oral traditions, ceremonies, and hands-on teaching, TEK has endured, even in the face of immense pressure. Now, with growing recognition of its scientific validity and practical efficacy, Indigenous communities are reclaiming their roles as stewards, often in partnership with state agencies, academic institutions, and environmental organizations.

Leading the Way: Indigenous-Led Wetland Restoration

Across California, tribal nations are demonstrating the power of their ancestral knowledge in restoring degraded wetlands. Their projects often encompass a broader vision than typical restoration efforts, integrating cultural revitalization, food sovereignty, and community well-being alongside ecological goals.

One of the most prominent examples is the Yurok Tribe along the Klamath River. For centuries, the Klamath River Estuary was a cornucopia, supporting vast runs of salmon, migratory birds, and diverse marine life. The tribe’s traditional management practices, including sophisticated fishing weirs and selective harvesting, ensured the health of these populations. However, the construction of dams upstream severely curtailed salmon runs and altered the estuarine environment. Today, the Yurok Tribe is at the forefront of efforts to remove the four Lower Klamath dams, a monumental undertaking that promises to restore the river’s natural flow and bring back the salmon, a keystone species for both the ecosystem and Yurok culture.

Beyond dam removal, the Yurok Tribe is actively restoring crucial estuarine habitats. Their scientists and traditional knowledge holders are working to replant native eelgrass beds, which serve as nurseries for fish and shellfish, sequester carbon, and stabilize sediments. "Our elders always taught us that the health of the river is our health," explains Rosie Clayburn, a Yurok tribal elder. "When the salmon thrive, when the lamprey return, when the eelgrass grows strong, our people are strong. This work isn’t just about the fish; it’s about our identity, our language, our future."

Further south, the Wiyot Tribe on the North Coast provides another powerful illustration. After decades of struggle, the tribe successfully reclaimed portions of their ancestral land, including Duluwat Island (also known as Indian Island) in Humboldt Bay, a sacred site where they held their World Renewal Ceremony. This island had been severely contaminated by a former lumber mill. The Wiyot Tribe, through painstaking efforts, removed over a million pounds of hazardous waste and began restoring the island’s natural wetland habitats. Their restoration efforts are holistic, incorporating traditional clam digging practices and the reintroduction of native wetland plants, enhancing biodiversity while also revitalizing cultural practices linked to the land.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, groups like the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe and the Confederated Villages of Lisjan Nation (Ohlone) are working to re-establish their connection to the region’s vast tidal marshes and sloughs. These wetlands, once teeming with life and managed by Ohlone ancestors, were largely destroyed to create salt ponds and urban development. Today, through land back initiatives and partnerships, these tribes are engaging in projects to restore tidal marsh habitat, reintroduce native plants, and educate the public about the historical and ecological significance of these vital ecosystems. Their efforts often involve the use of traditional materials and techniques for construction, blending ancient wisdom with modern restoration science.

The Core Principles of Indigenous Wetland Management

What makes these Indigenous-led efforts so effective and unique? Several core principles stand out:

- Holistic Perspective: Indigenous management views wetlands not in isolation but as interconnected parts of a larger landscape, including uplands, rivers, and coastal waters. The focus is on the health of the entire system, recognizing that everything is related.

- Long-Term Vision: Decisions are made with future generations in mind, often considering the impact seven generations ahead. This contrasts sharply with short-term economic or political cycles.

- Adaptive Management: TEK is not static; it is constantly evolving through observation and experience. Indigenous practitioners are adept at reading the landscape, adapting their practices to changing environmental conditions.

- Reciprocity and Respect: The relationship with the land is one of give and take, rooted in gratitude and respect. Resources are not "owned" but stewarded, ensuring their continued abundance.

- Cultural Integration: Restoration is not just an ecological act but a cultural one. Revitalizing wetlands means revitalizing language, ceremonies, traditional foods, and community well-being. "When we bring back the plants and animals, we bring back ourselves," notes an elder from the Ohlone community. "Our culture is inseparable from the land."

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite the growing recognition of TEK, Indigenous communities face significant hurdles. Funding remains a constant challenge, as does navigating complex state and federal regulations that often fail to recognize tribal sovereignty or traditional land management practices. The legacy of historical trauma, land dispossession, and lack of access to ancestral territories also continues to impact their ability to fully implement their visions.

However, there is a palpable shift occurring. California’s 30×30 initiative, aimed at conserving 30% of the state’s lands and coastal waters by 2030, explicitly recognizes the importance of Indigenous knowledge and co-management. State agencies are increasingly seeking partnerships with tribal nations, recognizing their unparalleled expertise. The "Land Back" movement is gaining momentum, returning ancestral lands to tribal stewardship, which is crucial for empowering Indigenous-led conservation.

The revitalization of California’s wetlands through Indigenous resource management is more than just an environmental endeavor; it is a profound act of cultural resurgence and ecological healing. It demonstrates that the most effective solutions to our modern environmental crises often lie not in novel technologies, but in the enduring wisdom of those who have lived in harmony with the land for millennia. By centering Indigenous voices and supporting their leadership, California can not only reclaim its vital wetlands but also forge a more resilient, equitable, and sustainable future for all its inhabitants. The reeds are rising again, guided by hands that remember the ancient rhythm of the land.