Bridging the Digital Divide: Native American Tribal Broadband Access Initiatives

The hum of the internet, a constant backdrop to modern life, remains a distant echo for millions across the United States. Nowhere is this silence more profound than on Native American tribal lands, where a stark digital divide continues to isolate communities, hinder progress, and perpetuate disparities. For decades, tribal nations have navigated a technological wilderness, but a new era of self-determination, fueled by unprecedented federal investment and tribal ingenuity, is finally paving the way for connection. The initiative to bridge this divide is not merely about laying fiber; it is a profound act of sovereignty, resilience, and a fundamental step towards equitable futures.

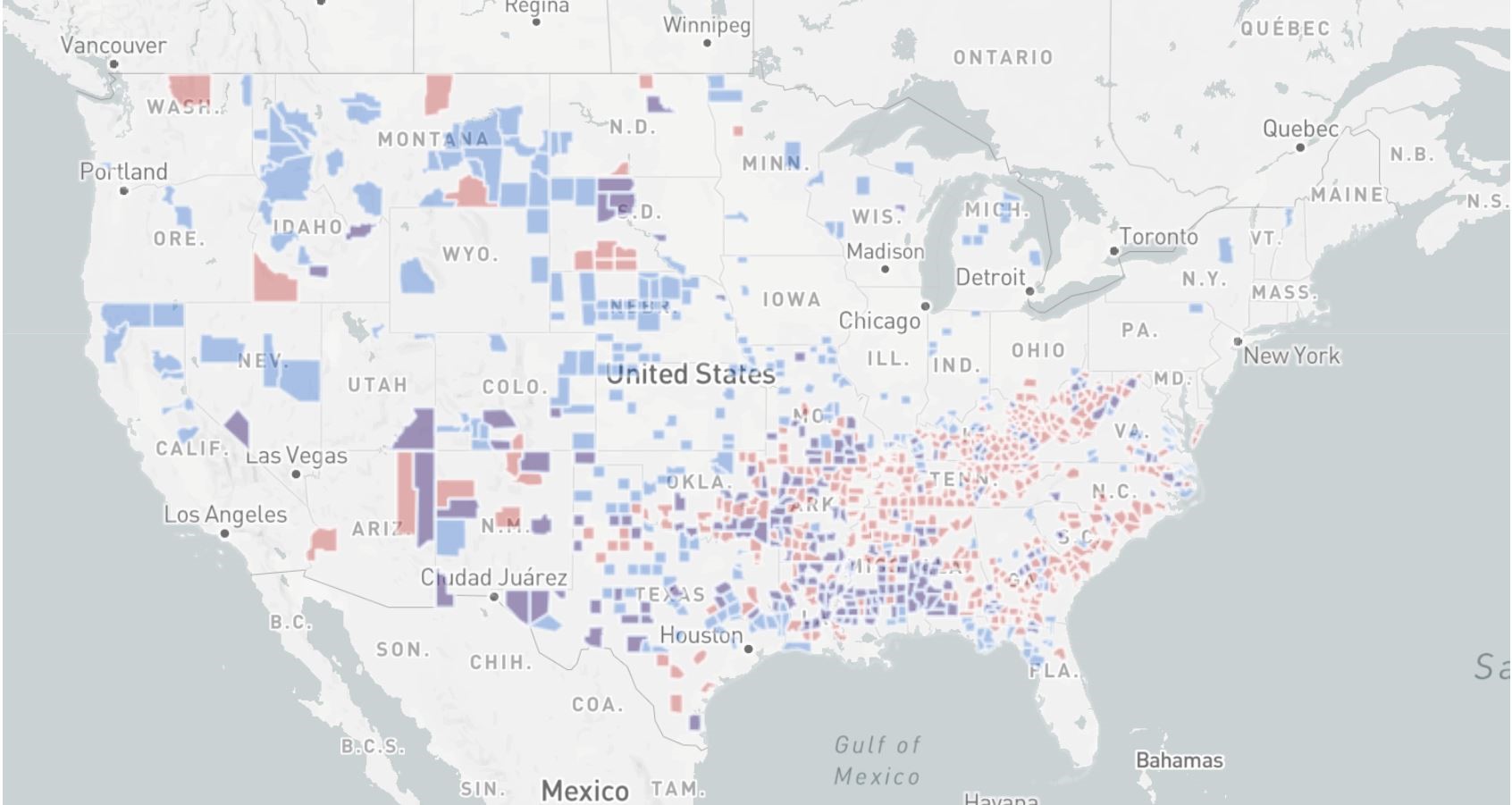

The scale of the problem is staggering. According to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), as recently as 2020, over 18% of people in rural areas and a staggering 22% of people on Tribal lands lacked access to fixed broadband service at threshold speeds, compared to a mere 1% in urban areas. Independent analyses often paint an even grimmer picture, with some estimates suggesting that up to 60% of residents on tribal lands lack reliable, high-speed internet. This isn’t just an inconvenience; it’s a barrier to education, healthcare, economic development, public safety, and the preservation of culture. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the "homework gap" became a chasm, telemedicine was often impossible, and tribal businesses struggled to compete in an increasingly online world. This historical neglect, often termed "digital redlining," is a direct legacy of systemic underinvestment and a lack of recognition of tribal sovereignty in infrastructure planning.

Tribal nations face a unique confluence of challenges in deploying broadband infrastructure. Geographically, many reservations are vast, remote, and characterized by rugged terrain and low population densities, making traditional private-sector investment unattractive due to perceived low returns on investment. Jurisdictional complexities further complicate matters; navigating right-of-way issues across trust lands, allotted lands, and checkerboard ownership patterns can be a labyrinthine process. Economically, the high cost of network deployment is compounded by the fact that many tribal communities grapple with high rates of poverty, making affordability of services a critical concern even once infrastructure is built. Historically, tribes also lacked the technical expertise and capacity-building resources necessary to plan, build, and operate complex broadband networks independently.

Despite these formidable hurdles, a powerful movement is underway, driven by a deep understanding that broadband access is not a luxury but a fundamental human right and a critical tool for self-determination. Central to this movement are innovative, tribal-led solutions and a significant influx of federal funding, recognizing that tribes are best positioned to address their own connectivity needs.

Federal programs have finally begun to acknowledge the specific needs of tribal nations. The National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) has emerged as a crucial partner, particularly through its Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program (TBCP). Established with $1 billion from the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 and an additional $2 billion from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the TBCP represents an unprecedented direct investment in tribal broadband infrastructure. This program empowers tribes to build, expand, and upgrade their own networks, acquire necessary equipment, and provide digital inclusion resources. Complementing this is the larger Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) program, also funded by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which allocates over $42.45 billion to states and territories, with specific provisions to ensure tribal needs are addressed.

Other vital funding sources include the USDA ReConnect Program, which finances broadband infrastructure in rural areas, and components of the FCC’s Universal Service Fund (USF), such as E-Rate for schools and libraries, and Lifeline for low-income households. Crucially, the CARES Act and the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) provided an emergency injection of funds during the pandemic, allowing many tribes to kickstart or accelerate broadband projects when the need was most acute. For example, ARPA’s State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, combined with direct tribal allocations, were instrumental in deploying temporary and permanent broadband solutions.

The true innovation, however, lies in the tribal-led approaches. Many tribes are choosing to build and own their own infrastructure, seeing it as an extension of their sovereignty and a means to control their technological destiny. The Navajo Nation, spanning over 27,000 square miles across Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, is a prime example. Facing some of the most challenging deployment conditions, the Navajo Nation has leveraged TBCP and ARPA funds for ambitious fiber-optic projects aimed at connecting their vast, dispersed communities. "For too long, our people have been isolated, unable to access online education, telemedicine, or even contact emergency services reliably," states a representative from the Navajo Nation Telecommunications Office. "Building our own network isn’t just about internet; it’s about empowerment, health, and preserving our way of life." Their efforts involve not just laying thousands of miles of fiber but also training their own workforce, fostering local economic development.

Similarly, the Santa Ana Pueblo in New Mexico has embarked on building its own fiber-to-the-home network, seeing local control as paramount. By forming their own tribal enterprise, they are ensuring that the network serves the specific needs of their community, from tribal government operations to individual households, and that revenues are reinvested locally. In Wisconsin, the Ho-Chunk Nation has utilized Citizens Broadband Radio Service (CBRS) spectrum to deploy a fixed wireless network, demonstrating how innovative technologies can bypass traditional deployment challenges, especially in areas where fiber is prohibitively expensive or difficult to lay. These initiatives underscore a fundamental shift: tribes are no longer waiting for external providers but are actively becoming the providers themselves.

The impact of these initiatives is transformative and multifaceted. In education, reliable broadband access means students can participate in remote learning, access digital libraries, and pursue higher education opportunities that were previously out of reach. It helps close the achievement gap and prepares tribal youth for a technology-driven future. In healthcare, telemedicine is revolutionizing access to specialists, mental health services, and routine care, particularly for elders and those in remote areas, reducing the need for arduous travel.

Economic development is seeing a significant boost. Broadband fosters entrepreneurship, enabling tribal members to start online businesses, participate in e-commerce, and access remote work opportunities, diversifying tribal economies beyond traditional sectors. It also attracts new businesses and provides the infrastructure necessary for economic growth within reservation boundaries. Beyond practical applications, broadband plays a crucial role in cultural preservation. It allows for the digital archiving of tribal languages, oral histories, and traditional knowledge, making these vital resources accessible to future generations and the wider world. It enables language revitalization programs and connects dispersed tribal members to their heritage. Furthermore, public safety is dramatically enhanced, with improved communication for emergency services, law enforcement, and critical infrastructure monitoring.

While immense progress has been made, significant challenges remain. Sustainability is a key concern; ensuring long-term funding for network maintenance, upgrades, and operational costs is crucial. Affordability continues to be a barrier for many tribal members, even with robust infrastructure. Programs like the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP) have been vital, but their long-term funding remains uncertain. Digital literacy and access to devices are also critical; simply providing internet access is not enough without the training and equipment to utilize it effectively. Finally, continued advocacy for tribal access to spectrum – the invisible airwaves that power wireless communication – is essential for tribes to maintain control over their wireless futures.

The journey to bridge the digital divide on Native American tribal lands is far from over, but the momentum is undeniable. What began as a desperate need has transformed into a powerful testament to tribal sovereignty, resilience, and strategic vision. By building their own networks, advocating for equitable funding, and embracing innovative technologies, Native American tribal nations are not just connecting their communities; they are asserting their right to participate fully in the 21st century, ensuring that the promise of a connected world reaches every corner of Indian Country. The sound of the internet, once a distant echo, is finally becoming a chorus of progress and self-determination.