The Last Stand of the Comanches: Adobe Walls and the Twilight of the Plains

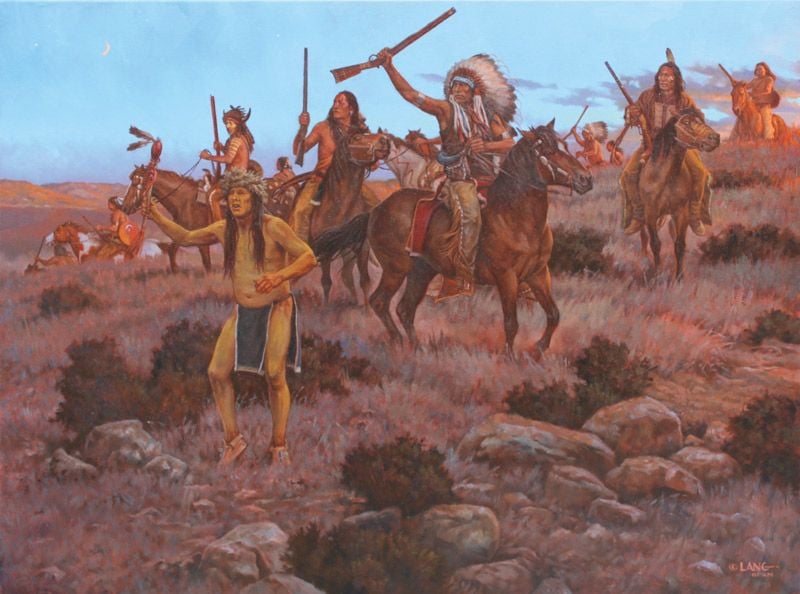

The dawn of June 27, 1874, broke not with the gentle light of a new day but with the thunderous charge of warriors, their war cries echoing across the Texas Panhandle. It was a desperate, final attempt by the indigenous nations of the Southern Plains – primarily Comanches, but also Kiowas and Cheyennes – to reclaim their ancestral lands and their vanishing way of life. The target: a cluster of buffalo hunter shacks known as Adobe Walls. This clash, often remembered for a legendary long-range rifle shot, was far more than a skirmish; it was a poignant, bloody epitaph for the free-roaming Plains Indians, a testament to their fierce resistance against an unstoppable tide of American expansion.

For centuries, the Comanche, or Nʉmʉnʉʉ ("The People"), had been the undisputed "Lords of the Southern Plains." Their empire stretched from the Arkansas River to the Rio Grande, a vast domain they defended with unparalleled equestrian skill and martial prowess. Central to their spiritual, cultural, and economic life was the American bison, or buffalo. These massive animals provided everything: food, clothing, shelter, tools, and spiritual connection. A Comanche without buffalo was a Comanche without a future.

However, by the 1870s, that future was rapidly eroding. The Treaty of Medicine Lodge in 1867 had promised vast reservations and protection from white encroachment, but like many treaties of the era, it was a paper tiger. White settlers, driven by the Homestead Act and the allure of free land, pushed westward. Railroads sliced through sacred hunting grounds. Most devastating of all was the relentless, systematic slaughter of the buffalo by white hide hunters. Armed with powerful Sharps rifles, these hunters decimated herds that had once numbered in the tens of millions, transforming vast grasslands into a macabre graveyard of bleached bones.

"The white man’s government broke its word, and the buffalo hunters were the spearhead of that broken promise," historian H.W. Brands observes in The American Colossus. "They were not just killing animals; they were destroying a civilization."

The Adobe Walls post, a crude collection of sod and adobe structures – a store, a saloon, and a blacksmith shop – stood as a brazen symbol of this invasion. It was a staging ground for the buffalo hunters, deep within what was supposedly protected Indian territory. For the Comanche, Kiowa, and Cheyenne, it was an intolerable affront, a cancerous growth on the heart of their world.

The call to war was amplified by spiritual fervor. A young Kwahadi Comanche war chief named Quanah Parker, son of a Comanche chief Peta Nocona and Cynthia Ann Parker, a white woman captured as a child, was a rising leader. Alongside him was Isa-tai (Coyote’s Buttocks), a Quahadi medicine man who claimed to possess potent spiritual powers. Isa-tai preached that a Great Spirit would protect the warriors, rendering the white men’s bullets harmless. He prophesied victory, instilling a powerful, almost desperate, hope among the suffering tribes. This blend of spiritual conviction and burning desire for retribution proved irresistible.

Quanah Parker, despite his mixed heritage, was a staunch defender of his mother’s adopted people and their traditional ways. He recognized the dire threat to the buffalo and the Comanche’s very existence. He and Isa-tai successfully forged an alliance of Comanche, Kiowa, and Cheyenne warriors, perhaps numbering between 250 and 700 men. Their plan was simple yet audacious: a surprise dawn attack on Adobe Walls, to wipe out the hunters and send a clear message.

On the night of June 26, 1874, the war party assembled. As they rode toward Adobe Walls, a minor incident nearly derailed the entire mission. One warrior’s horse broke free, drawing the attention of a sentinel. However, the hunters inside dismissed the noise as nothing more than a creaking ridgepole. This fortunate (for the hunters) misinterpretation allowed the element of surprise to largely remain intact.

Inside Adobe Walls, only 28 men and one woman were present. Among them were future legends of the American West: Bat Masterson, the fearless lawman, and Billy Dixon, a skilled scout and buffalo hunter. Just hours before the attack, the ridgepole of the saloon, weakened by age, began to crack. Several of the hunters, including Masterson, were awake attempting to repair it. This stroke of luck meant that when the attack came, they were not entirely asleep and unprepared.

As the sun began to peek over the horizon on June 27, the charge commenced. "It was a terrifying spectacle," recalled Billy Dixon years later. "Hundreds of Indians on horseback, yelling and shooting, coming at us like a great wave." The warriors, adorned in war paint and feathers, rode with a ferocity born of desperation. Their initial assault was overwhelming, catching the hunters off guard. Two men sleeping in a wagon outside were killed instantly. The hunters inside scrambled for their rifles, barricading doors and windows.

The adobe walls, though crude, proved surprisingly resilient against the arrows and older firearms of the warriors. The hunters, armed with their high-powered Sharps .50-90 "buffalo guns," possessed a significant advantage in range and firepower. These rifles, designed to fell a massive bison, could also be devastatingly effective against a human target.

The battle quickly devolved into a siege. The warriors surrounded the buildings, peppering them with arrows and bullets, attempting to set the sod structures alight. They made several charges, each met with a volley of accurate rifle fire that inflicted heavy casualties. Isa-tai’s prophecy of invulnerability, cruelly, proved false. Warrior after warrior fell, their belief in the medicine man’s power eroding with each loss. The initial momentum and spiritual conviction of the attack began to wane.

It was during this standoff that one of the most remarkable shots in frontier history occurred. On the second day of the siege, a small group of warriors gathered on a bluff nearly a mile away, seemingly out of range, taunting the hunters. Billy Dixon, a crack shot, decided to try a long shot. Using a borrowed .50-90 Sharps rifle, he aimed with an almost unbelievable precision.

"I saw an Indian on horseback, a long way off, sitting there as if he was waiting for us to come out," Dixon recounted. "I didn’t think I could hit him, but I thought I’d try." His shot, estimated at an incredible 1,538 yards (nearly seven-eighths of a mile), struck one of the mounted warriors, knocking him from his horse.

The effect was immediate and profound. "The Indians scattered like quail," Dixon observed. This "impossible shot" not only demoralized the remaining warriors but also instilled a near-mythical fear in them. How could the white men strike them from such a distance if not with magic? The failure of Isa-tai’s medicine and the terrifying accuracy of the hunters’ rifles combined to break the will of the attackers. By the end of the second day, the warriors, having suffered significant casualties and failed to dislodge the hunters, began to withdraw.

The Battle of Adobe Walls was a tactical victory for the buffalo hunters, who suffered only a handful of casualties. For the Comanche and their allies, it was a devastating defeat, both militarily and psychologically. It exposed the brutal reality that their traditional weapons and tactics were no match for the superior firepower of the Americans, and that their spiritual beliefs, however strong, could not stop bullets.

Adobe Walls directly precipitated the Red River War of 1874-75, a concerted U.S. Army campaign to permanently end Native American resistance on the Southern Plains. Under generals like Ranald S. Mackenzie, the army systematically destroyed Native American villages, horses, and most importantly, their remaining buffalo herds. Without their primary food source, the tribes were starved into submission.

Quanah Parker, after leading a valiant but ultimately futile resistance, eventually surrendered at Fort Sill in June 1875. His surrender marked the final chapter in the free-roaming life of the Comanches. Rather than fading into obscurity, Quanah Parker transformed. He became a prominent leader on the reservation, advocating for his people’s rights, establishing schools, and promoting economic development, all while preserving many aspects of Comanche culture. He became a successful rancher, a judge, and even befriended President Theodore Roosevelt. His adaptability and foresight were extraordinary, proving that even in defeat, the spirit of leadership could endure.

The Battle of Adobe Walls stands as a stark, poignant reminder of a critical turning point in American history. It was a desperate gamble by a proud people fighting for their very existence, a final, defiant roar against the encroachment that ultimately swallowed their world. The echo of those war cries across the Texas Panhandle, and the memory of the buffalo that once darkened the plains, serve as a powerful testament to the irreversible changes wrought by westward expansion and the tragic, profound loss suffered by the Indigenous nations of the Southern Plains. The twilight of their traditional way of life had truly begun.