Echoes of Time: Unveiling Arapaho Winter Counts as Pictorial Tribal Histories and Calendar Systems

Far more than mere calendars marking the passage of days, Arapaho Winter Counts are vibrant, living chronicles – intricate pictorial histories that encapsulate generations of tribal experience, knowledge, and identity. These unique historical records, meticulously kept by designated tribal historians, served as both an annual calendar system and a profound mnemonic device, preserving the collective memory of the Arapaho people and providing an invaluable lens into their pre-colonial and early reservation life. To understand Winter Counts is to understand a sophisticated, indigenous approach to history, one that prioritizes communal memory, visual storytelling, and a deep connection to the rhythms of the natural world.

The concept of a "Winter Count" is deceptively simple: a single drawing or pictograph created each year to represent the most significant event that occurred during the preceding twelve months, from one winter to the next. These images, often stylized and symbolic, were not merely illustrations; they were powerful mnemonic anchors, designed to trigger the detailed oral narratives associated with each year’s designated event. The keeper of the Winter Count, a highly respected elder or knowledge holder, would recount these stories, elaborating on the pictograph for the community, ensuring that the historical, cultural, and spiritual lessons of each year were passed down to younger generations.

The Anatomy of a Year-Name: More Than Just a Date

Unlike Western calendars that assign arbitrary numbers to days and years, Winter Counts operated on a system of "year-names." Each year was known by the event that defined it. For instance, a year might be called "The Year the Stars Fell" (referring to the dramatic Leonid meteor shower of 1833, an event so profound it was recorded by numerous Plains tribes, including the Arapaho), or "The Year of the Big Smallpox," or "The Year the Cheyenne and Arapaho Fought the Pawnee." These year-names, encapsulated in a single visual symbol, were deeply resonant, evoking a shared understanding of a particular period.

The pictographs themselves are a testament to the artistic skill and narrative economy of the Arapaho people. They are not elaborate scenes but rather concise, symbolic representations. A smallpox epidemic might be depicted by a figure covered in spots; a significant battle by a warrior and arrows; a particularly harsh winter by a human figure shivering or an animal freezing. The beauty lies in their evocative power – a single image unlocking a rich tapestry of communal memory. As Dr. Jeffrey D. Anderson, an expert on Plains Indian art, notes, "These images are not just pretty pictures; they are highly condensed narrative devices, carrying immense cultural weight."

The Keepers: Living Libraries of Tribal History

The role of the Winter Count keeper was one of immense responsibility and prestige. These individuals were not only skilled artists but also profound historians, eloquent storytellers, and cultural custodians. They possessed an encyclopedic knowledge of their people’s past, capable of reciting the history embedded in the count, often stretching back hundreds of years. The process of keeping the count involved careful observation of tribal life, consultation with other elders, and a discerning eye for identifying the single most impactful event of the year.

The passing of the keeper’s role was a significant tribal event, often involving extensive training and the transfer of sacred knowledge. The new keeper would not only inherit the physical count but also the vast oral tradition that gave it meaning, ensuring the continuity of the historical record and the preservation of tribal identity. This living archive system ensured that history was not a static collection of facts but a dynamic, evolving narrative, continually reinterpreted and understood within the context of contemporary life.

Materials and Evolution: From Hides to Ledger Books

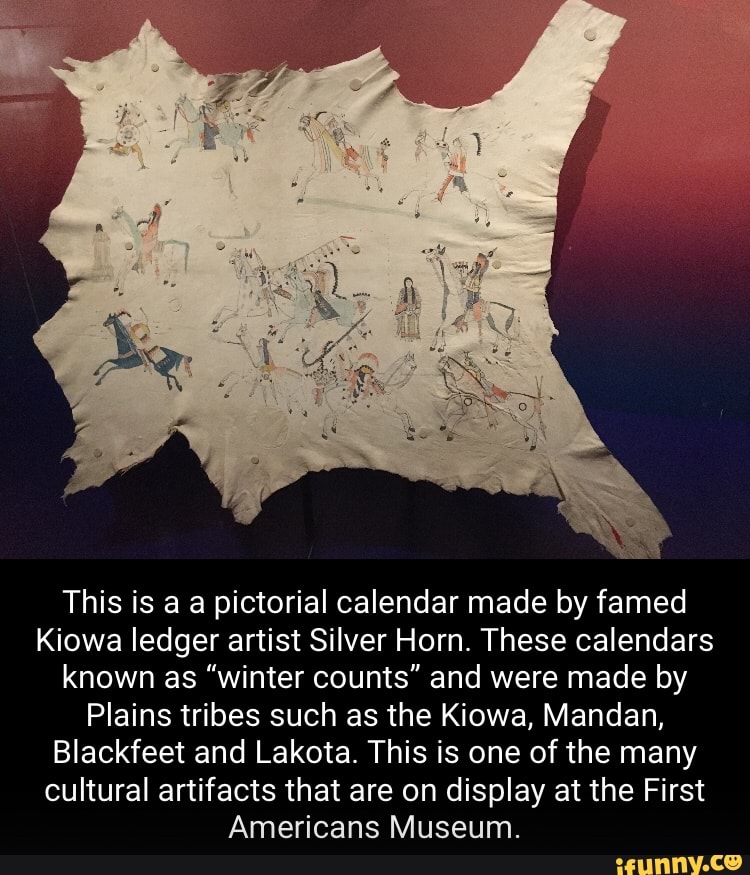

Traditionally, Arapaho Winter Counts were recorded on large animal hides, most commonly buffalo, deer, or elk. The images were painted or drawn directly onto the tanned hide, often in a spiral or linear pattern, beginning at the center and spiraling outwards, or in a continuous line across the surface. The hides were durable and portable, allowing the count to accompany the tribe as they moved across their vast territories.

With the arrival of European traders and settlers, and the subsequent establishment of reservations, the materials used for Winter Counts began to evolve. Muslin, canvas, and later, paper ledger books became common mediums. The transition to ledger books, often obtained from trading posts or military forts, marked a shift in artistic style as well. The rigid format of the ledger pages sometimes influenced the layout of the images, and new drawing tools like pencils, crayons, and ink allowed for different artistic expressions. However, the fundamental purpose and symbolic language of the counts remained consistent.

One fascinating aspect of the Winter Count tradition is the diversity of styles between different keepers and even within the same tribe. Each keeper developed their own unique hand, their own way of rendering the pictographs, making each count a distinct work of art and historical record. Yet, the core iconography and narrative function were universally understood within the community.

Content: A Comprehensive Tapestry of Life

The events recorded in Arapaho Winter Counts reflect the full spectrum of tribal life and experience. They include:

- Warfare and Raids: Battles with rival tribes (e.g., Pawnee, Ute, Crow, Shoshone), acts of bravery, significant victories, and defeats.

- Natural Phenomena: Severe winters, droughts, floods, unusual astronomical events (like the 1833 meteor shower or eclipses), and the movements of buffalo herds.

- Epidemics and Disease: Outbreaks of smallpox, cholera, whooping cough, or other diseases that significantly impacted the population. These entries often highlight the devastating impact of introduced diseases.

- Cultural and Ceremonial Events: Major tribal gatherings, important ceremonies (like the Sun Dance), the adoption of new rituals, or the transfer of sacred bundles.

- Economic and Subsistence Activities: Successful hunts, periods of famine, or significant trading expeditions.

- Political and Social Events: Changes in leadership, important council meetings, diplomatic encounters with other tribes or U.S. government officials, and significant movements of the tribe.

- Individual Achievements or Tragedies: The death of a prominent leader, a heroic act by a warrior, or other events that held collective significance.

These records provide an invaluable counter-narrative to Eurocentric historical accounts, offering an indigenous perspective on pivotal moments in history, including interactions with settlers and the U.S. military. For example, events like the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, a horrific attack on a peaceful encampment of Cheyenne and Arapaho, are recorded in several tribal Winter Counts, often with stark and emotional pictographs that convey the brutality and injustice of the event from the victims’ viewpoint.

Beyond History: Calendars, Identity, and Resilience

The Arapaho Winter Counts were more than just historical archives; they functioned as a sophisticated calendar system, allowing the tribe to track the passage of time, anticipate seasonal changes, and plan ceremonial cycles. By recounting the years, the community maintained a coherent understanding of its own timeline, anchoring individuals within a shared past and providing a framework for understanding the present.

Crucially, Winter Counts were instruments of cultural identity and continuity. In times of immense disruption – forced removal, the decimation of the buffalo, the imposition of reservation life, and attempts at cultural assimilation – these counts served as powerful reminders of who the Arapaho people were, where they came from, and the resilience they had demonstrated through generations. They were tangible proof of a rich and continuous history, a testament to their enduring sovereignty and cultural integrity.

In recent decades, there has been a significant movement among Arapaho descendants and other Plains tribes to reclaim, study, and revitalize their Winter Count traditions. Scholars, tribal historians, and cultural institutions are working together to identify existing counts (many of which are housed in museums and archives), interpret their narratives, and make them accessible to tribal members. Digital archiving, educational programs, and community workshops are helping to reconnect younger generations with these profound historical documents, ensuring that the wisdom and memory encoded in the pictographs continue to inform and inspire.

In a world increasingly reliant on written documentation, the Arapaho Winter Counts stand as a powerful reminder of the diverse ways in which humanity has chosen to record its journey. They are not static artifacts of a bygone era but living testaments to an ingenious system of historical preservation, a profound expression of cultural identity, and an enduring legacy of resilience. Each pictograph is a whisper from the past, an echo of time, inviting us to listen more closely to the rich and nuanced narratives of the Arapaho people.