Echoes in the Earth: Unearthing Ancient Louisiana’s Grand Trading Hubs and Monumental Earthworks

Louisiana, a state often celebrated for its vibrant Creole culture, jazz rhythms, and the economic might of the Mississippi River, holds a far deeper, more ancient narrative etched into its very soil. Long before European explorers navigated its waterways, this region was a dynamic crucible of human ingenuity, serving as a pivotal trading center and the site of monumental earthwork construction that predates Egypt’s pyramids and Stonehenge. These forgotten civilizations, primarily of the Archaic and Woodland periods, transformed the landscape with sophisticated earthworks and established vast trade networks, revealing a social complexity and organizational prowess that continues to astound archaeologists.

The story begins not with written records, but with the silent testimony of the earth itself – vast mounds, rings, and plazas painstakingly constructed by pre-Columbian indigenous peoples. These aren’t merely burial sites; they are evidence of advanced astronomical observation, complex societal structures, and a profound connection to the land. The most famous among these, Poverty Point, stands as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but it is merely the crown jewel in a constellation of hundreds of lesser-known yet equally significant earthworks scattered across the state, each whispering tales of ancient ambition and interconnectedness.

Poverty Point: A Marvel of the Ancient World

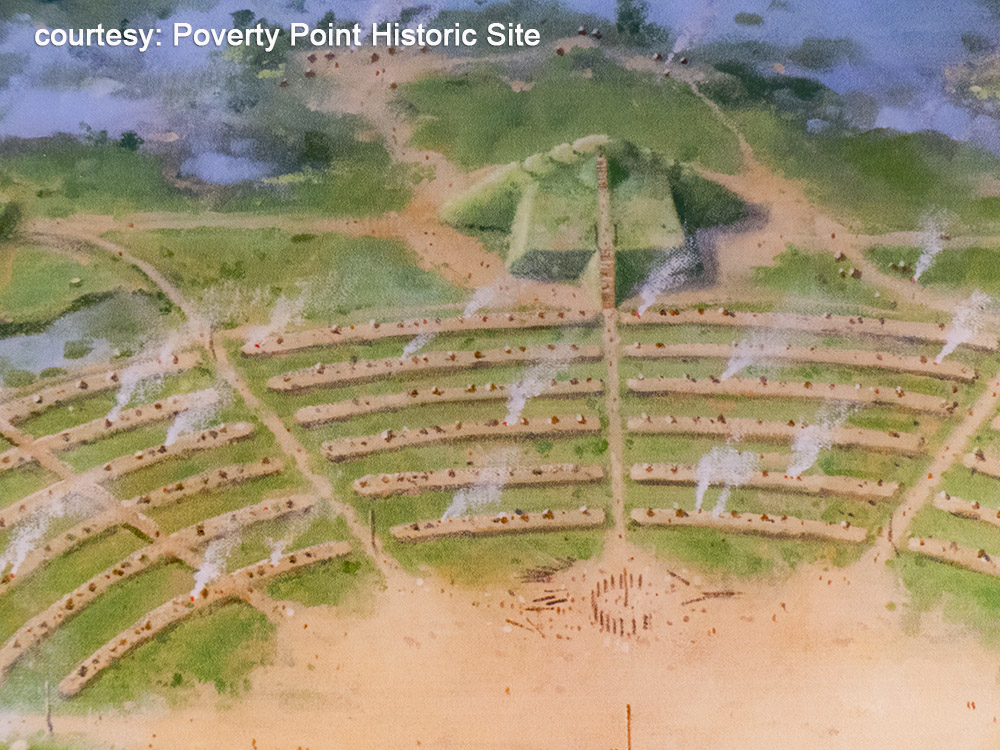

Located in West Carroll Parish, Poverty Point is arguably the most remarkable ancient site in North America. Built between 1700 and 1100 BC by a society of hunter-gatherers, its scale and precision defy conventional understandings of early human development. The site comprises a massive, concentric series of six C-shaped earthen ridges, interrupted by radial aisles, enclosing a central plaza approximately 37 acres in size. Beyond these ridges, five mounds stand sentinel, including the colossal Mound A, often called the "Bird Mound," which rises 72 feet high and measures 640 feet by 710 feet at its base. Its construction alone involved an estimated 238,000 cubic meters of earth, moved basket by basket, over a period of mere months or years, not centuries as initially hypothesized.

The sheer labor investment required to build Poverty Point suggests a highly organized society capable of mobilizing thousands of individuals. This wasn’t a simple village; it was a grand ceremonial and economic hub, drawing people from vast distances. "Poverty Point challenges our assumptions about what hunter-gatherer societies were capable of," explains Dr. Anya Sharma, a leading archaeologist specializing in North American prehistory. "The level of planning, coordination, and sustained effort required to construct something of this magnitude without agriculture, without advanced tools, is simply staggering. It speaks to a powerful social cohesion and a shared vision."

The purpose of Poverty Point remains a subject of intense study, but evidence points to its function as a multi-faceted center. It was likely a major gathering place for rituals, astronomical observations (some alignments suggest solstices and equinoxes), and, crucially, a central node in an expansive trade network.

Watson Brake: Pushing Back the Timeline

Even older than Poverty Point, the Watson Brake site near Monroe, Louisiana, rewrites the timeline for monumental construction in the Americas. Dating back to approximately 3400 BC – roughly 5,400 years ago – Watson Brake consists of 11 mounds, ranging from 3 to 25 feet tall, connected by a series of low ridges to form an oval-shaped enclosure almost 900 feet across. This makes it the oldest known mound complex in North America, predating Poverty Point by nearly 2,000 years.

The discovery of Watson Brake was revolutionary because it definitively demonstrated that complex earthworks were being built by pre-agricultural societies. For decades, archaeologists believed that settled agricultural communities were a prerequisite for such monumental construction. Watson Brake, along with other early Archaic sites, shattered that paradigm. It proved that hunter-gatherers, with their deep knowledge of seasonal resources, could achieve a level of sedentism and social organization necessary for large-scale public works. The people of Watson Brake were likely exploiting abundant aquatic resources from the nearby Ouachita River and its tributaries, allowing them the stability to undertake such ambitious projects.

The Ancient Trading Network: A Web of Connections

What ties these remarkable earthworks together, beyond their inherent architectural grandeur, is their role within a sophisticated and far-reaching trading network. Louisiana’s unique geography, nestled at the confluence of major river systems like the Mississippi, Red, and Ouachita, made it an ideal crossroads for ancient commerce. These waterways served as superhighways for canoes, allowing goods and ideas to flow across vast distances.

Evidence unearthed at Poverty Point and other sites paints a vivid picture of this ancient economy. Archaeologists have recovered exotic materials originating from thousands of miles away:

- Copper: Sourced from the Great Lakes region, primarily for ornamental purposes.

- Obsidian: Volcanic glass from the Rocky Mountains, prized for its sharp edges and used for tools.

- Chert: A type of flint from the Ohio River Valley, Texas, and Arkansas, essential for crafting projectile points and cutting tools.

- Galena: Lead ore from the Upper Mississippi Valley, used for pigments and possibly ceremonial objects.

- Quartz and Soapstone: From the Appalachian Mountains.

- Exotic Shells: From the Gulf Coast, traded inland for adornment.

These items weren’t merely utilitarian; many were prestige goods, symbols of status, power, or spiritual significance. The exchange was not simply about bartering goods; it facilitated the movement of knowledge, technologies, and cultural practices. The people who built Poverty Point and Watson Brake were not isolated communities; they were integral participants in a complex, interregional economy.

"The sheer volume and diversity of non-local materials found at Poverty Point are incredible," notes Dr. Sharma. "It tells us that this wasn’t just a place where people lived; it was a central marketplace, a hub where different cultures met, exchanged goods, and perhaps even shared ceremonies. The rivers were their lifelines, connecting them to a continent-wide network of exchange."

The People and Their Lifeways

The builders of these earthworks belonged to various indigenous cultures of the Archaic and early Woodland periods. While we don’t know their specific tribal names or languages, archaeological findings provide insights into their lives. They were skilled hunter-gatherers, intimately familiar with their environment. They hunted deer, bears, and smaller game, fished the bountiful rivers, and collected a wide array of nuts, seeds, and fruits. Their diet was diverse and rich, providing the caloric energy needed for monumental construction.

Their tools were made of stone, bone, wood, and shell. They developed sophisticated fishing techniques, including nets and weirs, and crafted intricate atlatls (spear throwers) for hunting. The transition from the Archaic to the Woodland period saw the gradual adoption of pottery and, much later, limited agriculture, but the ability to construct massive earthworks predates widespread farming, challenging long-held archaeological assumptions.

The social structure implied by these sites points to a leadership capable of inspiring and directing large groups of people. Whether these leaders were hereditary chiefs, religious figures, or influential individuals who gained power through charisma and resource distribution, their authority was sufficient to organize sustained public works projects that spanned generations.

Ongoing Discoveries and Preservation

Modern archaeological techniques, particularly LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), are continuously revealing new insights and even entirely new sites hidden beneath dense forest canopies. LiDAR technology allows archaeologists to strip away vegetation digitally, exposing subtle changes in elevation that betray the presence of ancient earthworks previously invisible from the ground. This has led to the discovery of hundreds of unrecorded mounds and complexes across Louisiana, underscoring the true extent of these ancient civilizations.

The preservation of these sites is paramount. Many have been lost to agricultural development, erosion, and looting over the centuries. Efforts by state agencies, federal programs, and organizations like the Archaeological Conservancy are crucial in protecting what remains. Poverty Point, as a State Historic Site and UNESCO World Heritage Site, benefits from extensive protection, but countless others remain vulnerable. Educating the public about their significance is a vital step in ensuring their survival for future generations.

A Legacy Etched in Time

The ancient trading centers and earthworks of Louisiana are more than just archaeological curiosities; they are profound testaments to human ingenuity, adaptability, and social complexity. They challenge our perceptions of pre-Columbian societies, revealing highly organized, interconnected cultures that shaped their environment on a grand scale. These monumental achievements stand as silent reminders of a vibrant, sophisticated past, urging us to look beyond the surface of the modern world and appreciate the deep, rich history etched into the very earth beneath our feet.

As Dr. Sharma eloquently puts it, "These ancient earthworks are not silent monuments; they are profound narratives, continually unfolding, reminding us that the human story in Louisiana is far older, far richer, and far more complex than most people ever imagine. They are a legacy that demands our attention, our respect, and our unwavering commitment to preservation." The echoes of these ancient builders still resonate, inviting us to listen, learn, and marvel at the enduring spirit of human endeavor.