Okay, here is a 1200-word journalistic article in English on ancient projectile point identification.

Silent Sentinels of Time: Unlocking Ancient Histories Through Projectile Point Identification

In the quiet earth, where centuries of dust settle upon forgotten landscapes, lie the most enduring and eloquent testimonies to human ingenuity and survival: ancient projectile points. Often mistakenly dismissed as mere "arrowheads," these meticulously crafted stone tools – spear points, dart points, and true arrowheads – are far more than simple hunting implements. They are the archaeological equivalent of fingerprints, each chip and curve telling a story of prehistoric technology, migration, cultural exchange, and the relentless pursuit of sustenance.

For archaeologists, the identification of these lithic artifacts is not just an academic exercise; it’s a critical gateway to understanding the chronology, cultural practices, and adaptive strategies of our ancient ancestors. Each distinctive form represents a moment frozen in time, a tangible link to a world shaped by ice ages, megafauna, and the pioneering spirit of early humans.

The "Why": Projectile Points as Chronological and Cultural Markers

Archaeologists often refer to projectile points as "time capsules" or "index fossils" because their styles evolved remarkably over millennia. Just as modern fashion or automobile design changes, so too did the preferred shapes and manufacturing techniques of these crucial tools. This stylistic progression allows researchers to date archaeological sites with surprising precision, even in the absence of organic materials suitable for radiocarbon dating.

"Every arrowhead tells a story, a silent whisper from the past, detailing the lives and ingenuity of people long gone," explains Dr. Evelyn Reed, a prominent lithic analyst at the University of Arizona. "They are our Rosetta Stone for deciphering prehistoric timelines and cultural boundaries. A specific point type found in a particular stratigraphic layer can instantly place a site within a known chronological period, linking it to broader patterns of human occupation and movement across continents."

Beyond dating, projectile points serve as invaluable cultural markers. Distinctive types are often associated with specific prehistoric cultures or groups, reflecting their unique technological traditions and aesthetic preferences. The widespread distribution of a particular point type might indicate extensive trade networks, migration routes, or the diffusion of ideas and technologies between different communities. Conversely, sharply defined regional variations highlight the isolation or distinct development of local groups.

Furthermore, studying these points reveals profound insights into ancient hunting strategies and resource exploitation. The size and robustness of a point can suggest the type of prey targeted – a large, heavy spear point for mammoth or bison, versus a small, delicate arrowhead for deer or fowl. The material used, often sourced from distant quarries, speaks volumes about ancient trade routes, territorial ranges, and geological knowledge.

The "How": Dissecting the Anatomy of a Point

Identifying projectile points requires a keen eye for detail and a systematic approach to morphology (shape), lithic technology (flaking patterns), and raw material analysis.

1. Morphology: The Blueprint of Design

The overall shape is the most immediate identifier. Key elements examined include:

- Blade: The main cutting edge. Is it straight, convex, concave, or serrated?

- Tip: The piercing end. Is it acute, blunt, or needle-like?

- Base: The end opposite the tip, crucial for hafting (attaching the point to a shaft).

- Hafting Element: This is perhaps the most diagnostic feature. It’s the part designed to be securely fastened to a shaft.

- Stemmed Points: Have a distinct "stem" or projection at the base, which can be contracting (tapering inwards), expanding (flaring outwards), or straight.

- Notched Points: Feature indentations along the sides or corners.

- Side-notched: Notches are cut into the sides of the blade, perpendicular to the long axis.

- Corner-notched: Notches are cut diagonally into the corners, creating distinct "barbs" or "shoulders."

- Basal-notched: Notches are cut into the base itself.

- Unnotched/Unstemmed (Lanceolate) Points: Lack a distinct stem or notches, often tapering smoothly to a base.

The precise dimensions – length, width, thickness – are also critical, as is the presence of features like "shoulders" (projections where the blade meets the hafting element) or "barbs" (pointed extensions from the shoulders).

2. Lithic Technology: The Art of Flaking

The way a point was flaked or "knapped" provides vital clues about the technological sophistication of its maker.

- Percussion Flaking: Involves striking a stone core with a hammerstone or antler billet to remove large flakes, shaping the initial form.

- Pressure Flaking: A more refined technique, using a pointed tool (like an antler tine or copper rod) to press off small, delicate flakes, creating sharp edges and intricate surface patterns.

- Fluting: A distinctive technique found on some early Paleoindian points, where one or more long, thin flakes are removed from the base towards the tip on both faces. This thinned the base for easier hafting and is a hallmark of Clovis and Folsom points.

- Collateral Flaking: Flakes removed from both edges meet precisely in the center, creating a medial ridge.

- Oblique Parallel Flaking: Flakes removed diagonally across the blade in parallel rows.

The skill evident in the flaking, the regularity of the flake scars, and the presence of specific techniques all contribute to identification.

3. Raw Material Analysis: Tracing Ancient Journeys

The type of stone used – chert, flint, obsidian, quartzite, chalcedony – can be incredibly diagnostic. Geologists can often trace the exact quarry source of the raw material, revealing patterns of trade, migration, or resource procurement. Finding obsidian from a specific volcanic outcrop hundreds of miles from a site, for example, paints a vivid picture of ancient exchange networks.

A Journey Through Time: Iconic Projectile Point Types

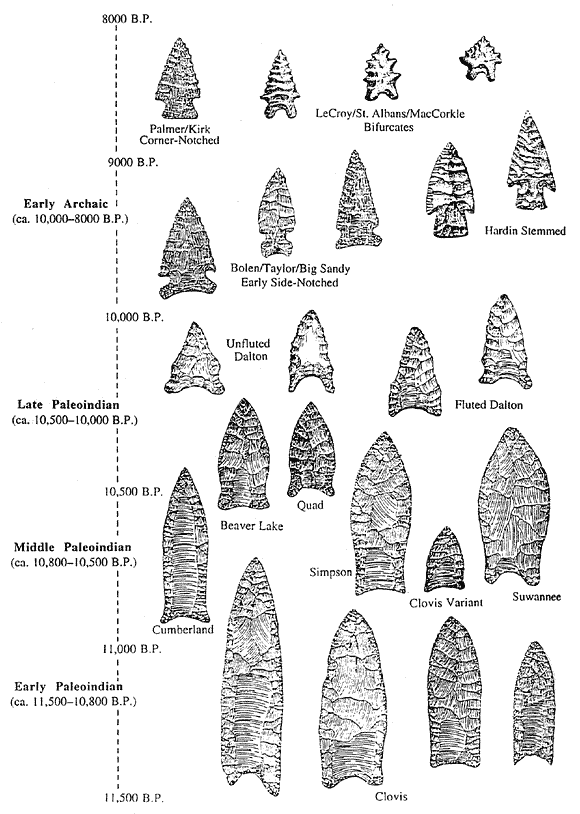

Let’s embark on a chronological journey through some of the most famous and diagnostic projectile point types:

1. Paleoindian Period (c. 13,000 – 9,000 years Before Present): The First Americans

This period is defined by the earliest inhabitants of the Americas, often associated with hunting megafauna.

- Clovis Points (c. 13,000 – 12,800 BP): The quintessential early American point. Large (7-15 cm), lanceolate (leaf-shaped), and characterized by distinctive "flutes" – long channels removed from the base on both faces. These are strongly associated with mammoth hunting. The discovery of Clovis points at sites like Blackwater Draw in New Mexico was pivotal in establishing the initial peopling of the Americas.

- Folsom Points (c. 12,800 – 12,000 BP): Smaller (2-7 cm) and more delicately fluted than Clovis points, with flutes often extending nearly to the tip. Folsom points are typically found in the Great Plains and are strongly associated with the specialized hunting of extinct bison (Bison antiquus).

- Plano Points (c. 12,000 – 9,000 BP): A diverse group of unfluted, lanceolate points (e.g., Eden, Scottsbluff, Agate Basin). These points represent a transition from the fluted traditions, often exhibiting exquisite collateral or oblique parallel flaking. They were used by groups who continued to hunt large game, including bison, after the megafauna associated with Clovis and Folsom began to decline.

2. Archaic Period (c. 9,000 – 3,000 BP): Adaptation and Diversity

As the climate warmed and megafauna disappeared, Archaic peoples adapted to a broader spectrum of resources. This period sees an explosion in projectile point diversity, reflecting regional adaptations and the increasing use of the atlatl (spear-thrower), which significantly increased the range and force of darts.

- Dalton Points (c. 10,500 – 9,900 BP): Early Archaic points, often lanceolate to triangular with concave bases and frequently serrated edges. They show evidence of extensive re-sharpening, a characteristic known as "beveling," which speaks to their value and reuse.

- Kirk Corner-Notched Points (c. 9,500 – 8,900 BP): A widespread Early Archaic type, characterized by deep corner notches, prominent shoulders, and serrated edges. Their broad distribution suggests significant cultural interaction.

- Bifurcate Base Points (c. 9,000 – 7,000 BP): A group of Early to Middle Archaic points (e.g., St. Albans, LeCroy, Kanawha) defined by a "fishtail" or "split" base. These highly diagnostic points are crucial markers for the eastern North American Archaic.

3. Woodland Period (c. 3,000 – 1,000 BP): Agriculture and Pottery

This era saw the development of pottery, settled villages, and early agriculture. Projectile points continued to evolve, often becoming smaller and more diverse. The introduction of the bow and arrow around 1,500 to 2,000 years ago led to a significant shift in point technology.

- Expanding Stemmed Points (e.g., Adena, Lamoka): Many Woodland points feature expanding stems or shallow corner notches.

- Triangular Points: Simple, unnotched triangular forms become increasingly common, particularly in later Woodland contexts, as true arrowheads designed for the bow and arrow.

4. Mississippian Period (c. 1,000 – 500 BP): Complex Societies

This late prehistoric period is marked by the rise of complex agricultural societies, mound building, and large ceremonial centers (like Cahokia). Projectile points from this era are predominantly small, thin, and triangular, reflecting the widespread adoption and refinement of the bow and arrow.

- Small Triangular Points (e.g., Madison, Cahokia): These "bird points" are typically very small, thin, and often unnotched or with tiny side notches. Their delicate construction allowed for high velocity and penetration with the bow.

Challenges and Nuances in Identification

While typology provides a robust framework, identification is not always straightforward.

- Resharpening: Points were valuable tools, often resharpened repeatedly, which can significantly alter their original shape and obscure diagnostic features.

- Breakage: Many recovered points are fragments, making identification more challenging.

- Regional Variation: Even within a broadly defined type, there can be subtle regional differences in size or manufacturing technique.

- Typological Overlap: Some point types share similar features, requiring careful consideration of multiple attributes and contextual information.

Conclusion: A Lingering Connection

The humble projectile point, a silent sentinel of time, continues to captivate archaeologists and enthusiasts alike. Each discovery offers a unique opportunity to connect with the past, to trace the journeys of ancient peoples, and to marvel at their ingenuity and resilience. From the fluted grace of a Clovis spear point to the delicate precision of a Mississippian arrowhead, these artifacts are more than just stones; they are profound testaments to the human spirit, etched in rock, waiting for us to decipher their ancient whispers. By meticulously identifying and interpreting them, we continue to piece together the extraordinary saga of our shared human history, one carefully crafted point at a time.