Echoes in Stone and Spirit: Unraveling Ancient Native American Spiritual Iconography

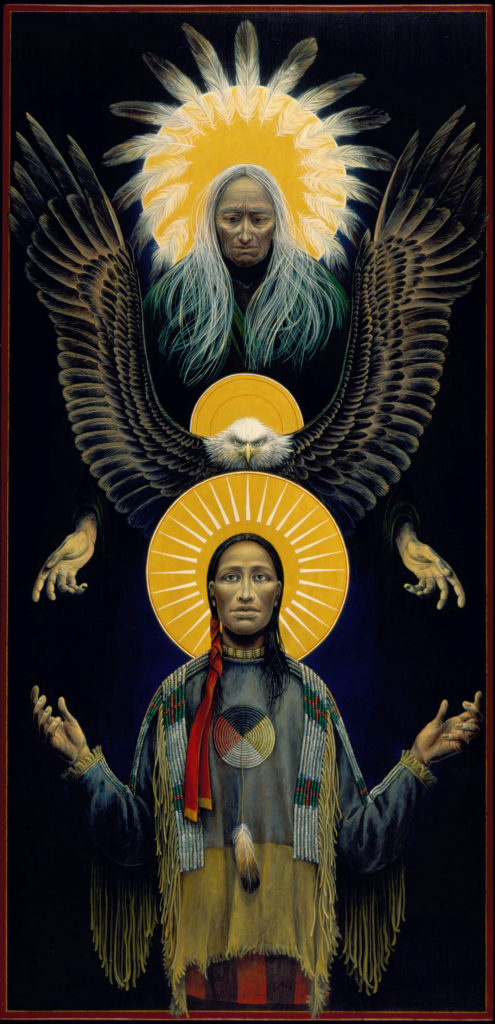

Across the vast and varied landscapes of North America, from the sun-baked canyons of the Southwest to the lush river valleys of the East, lie countless echoes of ancient spiritual worlds. These echoes are not merely whispers in the wind or forgotten tales; they are vibrant, enduring visual languages etched into stone, woven into textiles, molded into clay, and carved from wood. This is the rich tapestry of ancient Native American spiritual iconography – a profound lexicon of symbols, motifs, and sacred images that served not just as art, but as bridges to the divine, records of cosmic understanding, and guides for living in harmony with an interconnected universe.

Far from being a monolithic entity, ancient Native American cultures comprised hundreds of distinct nations, each with its unique spiritual traditions, mythologies, and artistic expressions. Yet, underlying this immense diversity were often shared fundamental principles: a deep reverence for the natural world, a belief in the inherent sacredness of all life, a profound connection to ancestors, and an understanding of the cyclical nature of existence. It is through their iconography that these intricate worldviews were made manifest, providing a window into the spiritual heart of a continent.

The Canvas of the Cosmos: Rock Art as Sacred Narratives

Perhaps the most direct and enduring forms of ancient spiritual iconography are the petroglyphs (images carved into rock) and pictographs (images painted onto rock). Found in thousands of sites across North America, from the Coso Range in California to the canyons of Utah and the deserts of New Mexico, these rock art panels are not random doodles but carefully placed, intentional narratives. They served as sacred spaces, often marking ceremonial sites, vision quest locations, or pathways for migrating peoples.

The motifs found in rock art are incredibly diverse, yet certain themes recur. Anthropomorphic figures, often depicted with exaggerated features, elaborate headdresses, or holding ceremonial objects, frequently represent shamans, spirit beings, or powerful ancestors. Zoomorphic figures, particularly deer, bighorn sheep, eagles, snakes, and bears, are ubiquitous, embodying animal spirits, totems, or guides. Cosmic symbols like sun discs, moons, stars, and spirals often denote celestial observations, the journey of life, or the sacred breath of the universe.

One fascinating example is the "Kokopelli" figure, prominent in the Southwest. This hump-backed flute player, often depicted dancing, is associated with fertility, joy, music, and the bringing of life-giving rain. His image, found on ancient Puebloan pottery and rock art, reminds us that spiritual iconography was often intertwined with daily existence and the very survival of communities dependent on agricultural cycles.

The Art of the Everyday: Pottery and Textiles

Beyond the grand scale of rock art, spiritual iconography permeated the fabric of daily life through more portable forms. Pottery, for instance, was not merely functional but a canvas for profound spiritual expression. The Mimbres culture, flourishing in what is now southwestern New Mexico between 1000 and 1130 CE, produced some of the most striking examples. Their black-on-white bowls feature intricate geometric patterns alongside highly stylized images of humans, animals, and mythical beings.

A particularly poignant aspect of Mimbres iconography is the "kill hole" – a small perforation often made in the center of a bowl when it was placed over the face of the deceased during burial rituals. This act, often accompanied by the breaking of the bowl, symbolized the release of the spirit from the vessel and its journey to the afterlife, a powerful metaphor for death and rebirth. The animals depicted on these bowls – rabbits, birds, fish, insects – are not simply decorative; they represent aspects of the Mimbres cosmos and their understanding of life’s intricate web.

Similarly, weaving traditions, particularly among cultures like the Ancestral Puebloans (formerly known as Anasazi), incorporated spiritual symbols into blankets, clothing, and ceremonial items. Geometric patterns, often representing mountains, rivers, clouds, or the four directions, held deep symbolic meaning, connecting the wearer or user to the land and the cosmos. The act of weaving itself was often a meditative, prayerful process, imbuing the finished product with spiritual power.

Mound Builders and the Mississippian World

In the eastern woodlands and southeastern United States, the Mississippian cultures (c. 800-1600 CE) left behind a monumental legacy of spiritual iconography, most notably through their vast earthworks and intricate shell, copper, and ceramic artifacts. Sites like Cahokia (near modern-day St. Louis), once a bustling metropolis larger than London in 1250 CE, featured massive platform mounds that served as foundations for temples and elite residences, aligning with celestial events and embodying a complex social and spiritual hierarchy.

The iconography of the Mississippian people, often referred to as the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (SECC), is rich with powerful symbols. The "Birdman" motif, a human figure adorned with wings and avian features, is a prevalent image, symbolizing spiritual flight, shamanic transformation, and connection to the upper world. The "Horned Serpent," a powerful underworld deity, often associated with water, fertility, and transformative power, is another recurring motif, reflecting a belief in a tripartite cosmos of upper, middle, and lower worlds.

Perhaps the most awe-inspiring example of Mississippian spiritual iconography is the Great Serpent Mound in Ohio. This colossal effigy mound, stretching over 1,300 feet, depicts a giant snake with an open mouth swallowing an egg-like shape. Aligned with lunar and solar events, it is believed to have served as a ceremonial calendar, a sacred observatory, and a powerful symbol of cosmic cycles, creation, and transformation. Its sheer scale and precision demonstrate an advanced understanding of both astronomy and spiritual cosmology.

The Enduring Power of Symbolism: Masks, Pipes, and Effigies

Beyond permanent structures, portable sacred objects played a crucial role. Ceremonial pipes, carved from stone or clay, often featured animal or human effigies, connecting the smoker to specific spirits or ancestors during prayer and ritual. Masks, particularly prominent in cultures across the continent, were not merely disguises but potent vessels that allowed wearers to embody spirits, deities, or ancestors, facilitating communication between the human and spiritual realms. The Iroquois False Face masks, though of a later tradition, powerfully illustrate the spiritual agency attributed to such objects.

Effigy mounds, like those found in Wisconsin in the shape of birds, bears, and other animals, further underscore the deep connection between animals, the landscape, and spiritual identity. These earthworks served as territorial markers, burial sites, and sacred places for ceremonies, embodying the spirits of the animals they represented.

Interpretation and Legacy

Understanding ancient Native American spiritual iconography is a complex endeavor. Meanings were often multi-layered, context-dependent, and sometimes esoteric, known only to initiates or specific spiritual leaders. The destruction of cultural practices, the loss of languages, and the forced displacement of peoples during colonization have unfortunately severed many direct interpretive links to these ancient symbols.

However, the legacy of this iconography is far from lost. Descendant communities continue to interpret, honor, and draw strength from these ancient symbols. Contemporary Native American artists, spiritual leaders, and scholars are engaged in a profound process of reclaiming and revitalizing these visual languages, connecting the past to the present and ensuring their continued resonance.

For the non-indigenous observer, these ancient icons offer a powerful reminder of the rich spiritual heritage of North America. They invite us to look beyond the surface, to appreciate the profound intellectual and spiritual sophistication of these cultures, and to recognize the universal human quest for meaning, connection, and understanding of our place in the cosmos. The petroglyphs, the pottery, the mounds, and the effigies are not just relics; they are living testaments to enduring faith, deep wisdom, and the timeless power of the human spirit to express its most sacred truths. They stand as a powerful call for respect, preservation, and a deeper appreciation of the indigenous voices that shaped, and continue to shape, the spiritual landscape of this continent.