The Arctic, a landscape of stark beauty and unforgiving extremes, has been home to the Inuit for thousands of years. Far from being merely survivors, the ancient Inuit were masters of adaptation, developing an intricate way of life that allowed them to thrive in one of the planet’s most challenging environments. Their ingenuity, deep understanding of nature, and robust social structures offer a compelling testament to human resilience.

Understanding the ancient Inuit way of life requires us to step back into a world shaped by ice, snow, and the rhythm of the seasons. It was a life intricately woven with the land and sea, demanding constant innovation and profound respect for every living creature.

The Arctic Environment: A Formidable Home

The circumpolar Arctic region, stretching across Alaska, Canada, Greenland, and Siberia, presented unique challenges. Extreme cold, long periods of darkness, treacherous sea ice, and vast, often featureless terrain defined their existence. Resources were scarce and seasonal, necessitating a nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyle.

Despite these formidable conditions, the Inuit did not just endure; they flourished. Their success lay in their unparalleled ability to interpret and adapt to their environment, transforming perceived limitations into opportunities for survival and cultural enrichment.

Masters of the Hunt: Sustenance and Survival

Hunting was the cornerstone of ancient Inuit life, providing not only food but also materials for clothing, shelter, tools, and fuel. Marine mammals were primary targets, offering high-fat, high-protein sustenance essential for warmth and energy.

Seals, in particular, were vital. Inuit hunters developed sophisticated techniques, including waiting patiently at breathing holes (mauliqtuq hunting) or ambushing seals basking on ice. Every part of the seal was utilized: meat for food, blubber for fuel and light, skin for clothing and boat coverings, and bones for tools.

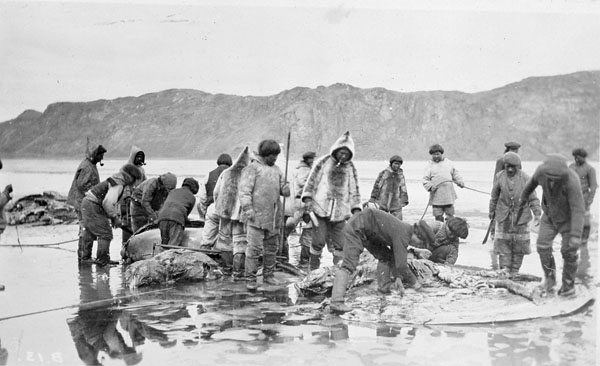

Whales, especially bowhead and beluga, were also crucial, particularly for larger communities. The immense size of these animals required communal hunting efforts and provided vast quantities of food, oil, and bone, sustaining entire settlements for extended periods.

On land, caribou were a significant resource, providing meat, warm hides for clothing, and antlers for tools. Muskox, polar bears, and various birds and fish supplemented their diet, showcasing a diverse and strategic approach to foraging.

Ingenious Tools and Technology

The Inuit developed an impressive array of tools from available natural materials like bone, antler, ivory, stone, and driftwood. These tools were not just functional but often elegantly designed, reflecting a deep understanding of physics and material properties.

The toggle harpoon stands out as a prime example of Inuit engineering. Designed to detach from the shaft after striking an animal, with the toggle head turning sideways to secure it under the skin, it minimized loss and maximized efficiency.

Other essential tools included:

- The ulu (women’s knife) for skinning, butchering, and preparing food.

- Snow knives for cutting snow blocks for igloos.

- Drills made from bone and stone for crafting.

- Bow drills for starting fires.

Their toolkit was perfectly suited to their environment and tasks.

Shelter in a Frozen World

Inuit shelter solutions were as diverse as the Arctic seasons. The iconic igloo, or snow house, was a marvel of architectural ingenuity, providing excellent insulation and warmth during winter hunts or travels.

Constructed from precisely cut snow blocks arranged in a self-supporting dome, igloos could be built quickly and efficiently. A small entrance tunnel trapped cold air, while a raised sleeping platform helped retain warmth. They were temporary but incredibly effective.

For more permanent settlements, especially in areas with less reliable snow, the Inuit built qarmaq – semi-subterranean houses made from sod, stone, and whalebone or driftwood supports. These offered robust, long-term protection against the elements.

During the warmer months, when ice receded and hunting patterns shifted, portable tupiq (tents) made from animal skins provided adaptable shelter, allowing for greater mobility.

Clothing: A Second Skin Against the Cold

Inuit clothing was a masterpiece of cold-weather engineering. Designed for extreme insulation, flexibility, and durability, it was often made from multiple layers of animal skins, primarily caribou and seal.

The typical outfit included a layered system: an inner parka with fur facing inward for warmth, and an outer parka with fur facing outward for protection against wind and snow. These garments, along with trousers, mittens, and kamiks (boots), were meticulously sewn, often with intricate waterproof seams using sinew.

The choice of animal skin was crucial: caribou hide provided exceptional warmth due to its hollow hairs, while seal skin offered excellent water resistance. This sophisticated understanding of materials was critical for survival.

Social Fabric: Community, Sharing, and Respect

Ancient Inuit society was built on principles of cooperation, sharing, and deep respect for elders and the environment. The harsh Arctic demanded collective effort; no individual could survive alone.

Family units and extended kinship networks formed the core of communities. Decisions were often made by consensus, with elders revered for their wisdom, experience, and knowledge of traditions and survival techniques. Their guidance was invaluable.

The practice of food sharing was paramount. A successful hunt benefited the entire community, ensuring that everyone had enough to eat, especially during lean times. This reciprocal system fostered strong bonds and ensured collective survival.

Spirituality and Worldview: Harmony with Nature

The Inuit held a rich animistic worldview, believing that spirits inhabited all living things and even inanimate objects. The land, sea, and animals were not just resources but entities deserving of respect and reverence.

Shamans, or Angakkuq, played a crucial role as intermediaries between the human and spirit worlds. They conducted rituals, healed the sick, and sought guidance to ensure successful hunts and community well-being.

Taboos and rituals were observed to maintain balance and harmony with the spirit world, particularly concerning hunted animals. The proper treatment of an animal’s remains was believed to ensure its spirit would return, allowing for future successful hunts.

Art, Storytelling, and Oral Traditions

Inuit art was functional and deeply spiritual, reflecting their daily lives, beliefs, and connection to the Arctic. Carvings from bone, ivory, and stone depicted animals, human figures, and mythological beings, often imbued with spiritual significance.

Inukshuks, stone cairns built by the Inuit, served as navigational aids, hunting markers, and spiritual symbols across the vast landscape. They stand as enduring testaments to human presence and ingenuity.

Oral tradition was the primary means of transmitting knowledge, history, myths, and legends. Storytelling, songs, and drum dancing were vital cultural practices, preserving ancestral wisdom and entertaining during long winter nights.

Transportation: Navigating Land and Sea

Mobility was essential for hunting and seasonal migrations. The Inuit developed highly effective modes of transport adapted to their environment.

Dogsleds, or qamutiks, pulled by teams of dogs, were indispensable for winter travel, hauling supplies, and transporting people across vast, snowy distances. The design of the sleds minimized friction and maximized load capacity.

The kayak (qajaq), a single-person, covered boat made from animal skins stretched over a wooden or bone frame, was a masterpiece of design for hunting marine mammals and navigating icy waters quietly and efficiently.

The umiak, a larger, open boat, also made from skin over a frame, was used for transporting families, goods, and for communal whaling expeditions, capable of carrying multiple people and substantial cargo.

Diet and Food Preservation

The ancient Inuit diet was high in protein and fat, derived almost entirely from animal sources. They consumed meat and blubber raw (as in mukluk, whale blubber and skin), which provided essential vitamins (like Vitamin C, found in fresh organ meats) that were scarce in their environment.

Food preservation techniques were critical for surviving periods of scarcity. Meat was cached under rocks, frozen, or dried (like pemmican, a mixture of dried meat, fat, and berries) to ensure a year-round supply.

Resilience and Ingenuity: Lessons for Today

The ancient Inuit way of life stands as a powerful example of human adaptability and sustainable living. Their profound ecological knowledge, innovative technologies, and strong community bonds allowed them to thrive in an environment that would defeat most without such wisdom.

Their legacy is one of unparalleled resilience, demonstrating how deep respect for nature and collective effort can lead to enduring success even in the face of extreme adversity. It’s a testament to the power of traditional knowledge and human spirit.

Conclusion

The ancient Inuit way of life was a remarkable tapestry woven from ingenuity, adaptability, and an profound connection to the Arctic environment. From their sophisticated hunting techniques and innovative tools to their unique shelters and intricate social structures, every aspect of their existence was a testament to their resilience.

They not only survived but flourished, creating a rich cultural heritage built on community, respect for nature, and an extraordinary capacity for innovation. Their story continues to inspire, offering valuable insights into sustainable living and the enduring strength of the human spirit in harmony with the natural world.

_0.jpg?w=200&resize=200,135&ssl=1)