Okay, here is a 1200-word journalistic article in English on Wovoka and the Ghost Dance prophecy.

The Echo of a Vanished World: Wovoka and the Ghost Dance Prophecy

In the twilight years of the 19th century, a profound despair settled over the Native American nations of the Great Plains and beyond. Their lands had been stolen, their cultures suppressed, and their very way of life systematically dismantled by the relentless westward expansion of the United States. The buffalo, once numbering in the tens of millions, were all but extinct, leaving starvation and destitution in their wake. Treaties were broken as quickly as they were signed, and the people were confined to ever-shrinking reservations, their spirits crushed under the weight of an insurmountable oppression. It was into this crucible of suffering that a desperate, yet radiant, hope emerged: the Ghost Dance prophecy, born from the vision of a Paiute prophet named Wovoka.

This was not merely a dance; it was a spiritual movement, a desperate prayer for renewal, a final, poignant testament to a people’s enduring faith in the face of annihilation. It promised nothing less than the resurrection of a vanished world, a return to sovereignty, and the dawn of a new era free from the white man’s tyranny. Its message, initially one of peace and love, would ultimately be tragically twisted by fear and misunderstanding, culminating in one of the most infamous massacres in American history.

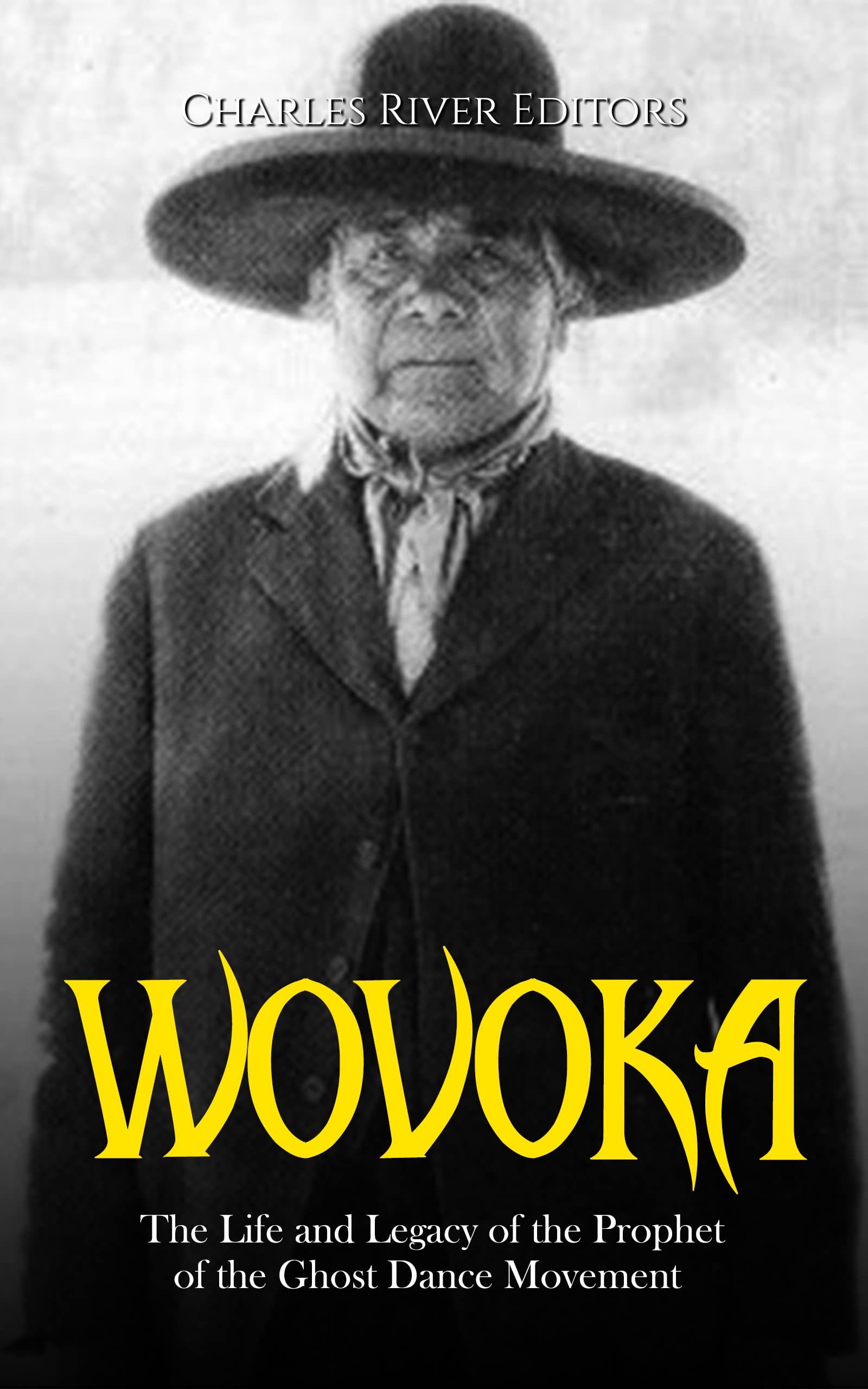

The Visionary: Wovoka, the Paiute Messiah

Born around 1856 near Smith Valley, Nevada, Wovoka was known to the white settlers as Jack Wilson. His early life was typical of many Paiutes of his time, marked by poverty and intermittent labor on local ranches, including one owned by David Wilson, from whom he took his English name. Wovoka was not initially a chief or a medicine man of great renown, but he possessed a deep spiritual sensitivity and a reputation for quiet contemplation.

His transformative experience came in 1889, during a solar eclipse on New Year’s Day. While gravely ill with a fever, Wovoka fell into a deep trance. He later recounted that he had died and ascended to the spirit world, where he met God. This divine encounter, he claimed, bestowed upon him a sacred mission. God showed him a beautiful land, teeming with healthy buffalo and the spirits of departed ancestors. He was given a message of peace, love, and reconciliation, and taught a ceremonial dance.

Wovoka’s message was simple yet profound: "When the sun died, I went up to Heaven and saw God and all the people who have died a long time ago. God told me to come back and tell my people they must be good and love one another, and not fight, or steal, or lie. He gave me this dance and told me to give it to my people." He promised that if the people faithfully performed this new "Ghost Dance," lived righteously, and rejected the white man’s ways (especially alcohol), a cataclysmic event would occur. The earth would shake, the white settlers would be swallowed up, the buffalo would return, and all deceased Native Americans would be resurrected, reuniting with their living relatives in a restored, pristine world.

Crucially, Wovoka’s original prophecy was explicitly non-violent. He urged his followers to live in harmony, avoid conflict, and perform the dance with a pure heart. "Do no harm to anyone," he instructed. "Do not tell lies." His vision was not one of armed rebellion, but of spiritual cleansing and divine intervention.

The Dance Spreads Like Wildfire

News of Wovoka’s vision and the accompanying Ghost Dance spread rapidly across the reservations, carried by emissaries from various tribes who traveled to Nevada to learn directly from the prophet. The message resonated deeply with a people yearning for salvation. For tribes like the Lakota (Sioux), Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Kiowa, the Ghost Dance offered a potent antidote to their suffering, a tangible hope in a world devoid of it.

The dance itself was a communal affair, often performed in a large circle. Participants would hold hands, sway rhythmically, and chant sacred songs for hours, sometimes days, until they fell into trances. During these trances, they believed they communed directly with their ancestors and experienced visions of the promised new world. The dance was physically and emotionally exhausting, yet spiritually invigorating. It was a powerful expression of cultural identity and communal solidarity, a defiant act of hope against overwhelming odds.

As the Ghost Dance spread, various tribes adapted it to their own traditions and beliefs. Some Lakota, for instance, began to wear "ghost shirts," cotton garments painted with sacred symbols. While Wovoka himself never claimed these shirts would repel bullets, some Lakota followers came to believe they offered supernatural protection from the soldiers’ weapons. This belief, born of desperation and cultural interpretation, would tragically fuel the fears of white authorities.

Fear and Misinterpretation: The White Man’s Panic

The rapid spread of the Ghost Dance did not go unnoticed by the U.S. government and white settlers. Accustomed to suppressing any sign of Native American independence, they viewed the dance with suspicion, fear, and outright paranoia. The sight of hundreds of Native Americans dancing for days, seemingly in a frenzy, fueled sensationalist newspaper reports that depicted the Ghost Dance as a prelude to a violent uprising.

Indian agents, many of whom harbored deep prejudices and little understanding of Native American spirituality, sent alarming dispatches to Washington D.C. They reported that the dance was inciting the Indians to rebellion, despite the fact that most reports from actual observers, including some military personnel, noted the peaceful nature of the gatherings. Colonel James W. Forsyth, commander of the 7th Cavalry, for example, observed that the dancers "do no harm to anyone, they simply dance and sing."

However, the prevailing narrative was one of impending "Indian war." The desperate hope of the Native Americans was fundamentally misunderstood and deliberately misinterpreted as a threat. The idea of "bulletproof shirts" further inflamed white fears, suggesting an armed, fanatical resistance. This fear, often rooted in guilt over past injustices and a desire to consolidate power, created an environment ripe for tragedy.

The Road to Wounded Knee

The most volatile situation developed among the Lakota Sioux on the Pine Ridge and Standing Rock Reservations in South Dakota. Here, the Ghost Dance took on a particularly fervent character. Many Lakota, including the revered Sitting Bull, though initially skeptical, eventually allowed the dance among his followers. His very presence, a symbol of unyielding resistance, was seen by authorities as a dangerous endorsement of the movement.

Agent James McLaughlin at Standing Rock, convinced that Sitting Bull was the primary instigator of the Ghost Dance "trouble," ordered his arrest. On December 15, 1890, Lakota police officers attempted to apprehend the legendary chief. In the ensuing struggle, Sitting Bull was killed, along with several police officers and his followers. His death sent shockwaves through the Lakota nation, further deepening their despair and increasing tensions.

Following Sitting Bull’s death, many of his followers, fearing further reprisal, fled the Standing Rock Reservation. Among them was Chief Big Foot and his band of Miniconjou Lakota, who were traveling towards the Pine Ridge Agency, seeking safety with Chief Red Cloud. They were already weakened by cold and illness, Big Foot himself suffering from pneumonia.

The Massacre at Wounded Knee

On December 28, 1890, the Seventh Cavalry Regiment, the same unit that had suffered heavy losses at Little Bighorn fourteen years prior, intercepted Big Foot’s band near Wounded Knee Creek. The Lakota, numbering around 350, mostly women and children, were surrounded and ordered to camp there. The next morning, December 29, the soldiers moved to disarm the Lakota.

The situation was tense and volatile. As soldiers collected rifles, a deaf man named Black Coyote, who apparently did not understand the order, resisted giving up his weapon. A shot was fired – its origin remains disputed, possibly accidental, possibly from a Lakota, or from a nervous soldier. That single shot shattered the fragile peace.

What followed was not a battle, but a massacre. The soldiers, perhaps still fueled by the ghosts of Little Bighorn and the pervasive fear of a Ghost Dance uprising, opened fire indiscriminately. They used their rifles and devastating Hotchkiss rapid-fire cannons, which fired explosive shells, scything down men, women, and children. Many Lakota men had already surrendered their weapons, and few were armed. Those who tried to flee were hunted down and killed.

When the slaughter finally ceased, the snow-covered ground was stained crimson. Nearly 300 Lakota lay dead or dying, two-thirds of whom were women and children. The soldiers suffered around 25 killed, mostly from friendly fire. The bodies of the Lakota, frozen in grotesque positions, were left on the ground for three days before being buried in a mass grave. Wounded Knee marked the brutal suppression of the Ghost Dance movement and is widely considered the last major armed conflict between the U.S. government and Native Americans.

The Legacy of Hope and Tragedy

Wovoka himself lived a long life after Wounded Knee, dying in 1932. He continued to preach his message of peace and the eventual return of the ancestors, but the widespread fervor of the Ghost Dance never returned. The massacre had brutally demonstrated the futility of even spiritual resistance against the overwhelming might of the U.S. military.

The Ghost Dance prophecy remains a poignant and complex chapter in American history. It was a desperate, yet beautiful, expression of hope and cultural resilience in the face of profound adversity. It was a testament to the enduring human need for meaning and spiritual solace, even when all earthly hope seems lost. But it also stands as a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of cultural misunderstanding, virulent paranoia, and the unchecked power of a dominant society.

Wounded Knee, born from the fear of a peaceful spiritual movement, is a scar on the conscience of the nation. It serves as a somber epitaph for a vanished world, but also as an eternal echo of the enduring spirit of a people who, even in their darkest hour, sought solace in a dance, a song, and a dream of renewal. The Ghost Dance may have been suppressed, but its spirit of resistance and hope, though quieted, has never truly died.