Wilma Mankiller: A Chief Who Forged a Path of Self-Determination

In the annals of American leadership, few figures shine as brightly and with such quiet, unwavering power as Wilma Pearl Mankiller. The first woman to serve as Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, Mankiller was more than just a political leader; she was a visionary, a healer of communities, and a living embodiment of resilience who reshaped the landscape of indigenous self-governance. Her decade-long tenure, from 1985 to 1995, was a period of unprecedented growth, cultural revitalization, and a profound reassertion of tribal sovereignty, leaving an indelible mark not only on the Cherokee Nation but on indigenous peoples worldwide.

Born in 1945 in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, the capital of the Cherokee Nation, Wilma Mankiller’s early life was marked by the pervasive poverty and displacement that characterized many Native American communities in the mid-20th century. Her family, like thousands of others, was part of the federal government’s "Indian Relocation Program," a misguided policy designed to assimilate Native Americans by moving them from reservations to urban centers. At age 11, Wilma moved with her family to San Francisco, a jarring transition from rural Oklahoma to the bustling, alien environment of a major city.

This urban experience, while initially disorienting, proved to be a crucible for her future activism. Exposed to the burgeoning civil rights movement and the Red Power movement of the 1960s and 70s, Mankiller became politicized. She participated in the historic 1969 occupation of Alcatraz Island, a pivotal moment for Native American activism that demanded the return of federal lands to indigenous control. This period ignited a deep sense of justice and a commitment to her people’s rights. As she later reflected, "My work with the Alcatraz occupiers solidified my belief that grassroots efforts could truly bring about change."

Yet, despite her urban activism, a powerful pull drew her back to her ancestral lands. In the mid-1970s, Wilma returned to Oklahoma, bringing her two daughters with her. She felt an urgent need to reconnect with her roots, language, and culture, and to contribute directly to the well-being of her community. This return marked a crucial turning point, shifting her focus from broad-based protest to direct, community-level development.

Her entry into tribal politics was not through a grand declaration, but through humble, dedicated work. She started as a community developer, focusing on local, grassroots initiatives. Her philosophy was simple yet profound: empower people to help themselves. One of her most celebrated early projects was the Bell Water Project, where she organized a community to lay 16 miles of water lines to bring clean drinking water to their homes. Instead of waiting for federal funding or external contractors, Mankiller encouraged the community to perform the labor themselves, fostering a sense of ownership, pride, and collective achievement. "My role was to make the invisible visible," she often said, referring to the hidden talents and capabilities within her community. "I taught them how to access resources and organize themselves, but they did the work."

Her effectiveness and dedication quickly caught the attention of Principal Chief Ross Swimmer, who, in a bold and unprecedented move, selected Mankiller as his running mate for Deputy Chief in 1983. The decision was met with resistance and outright sexism. Many Cherokee, both men and women, were uncomfortable with the idea of a woman in such a prominent leadership role, a sentiment rooted in historical and cultural patriarchal norms that had often been reinforced by colonial influences. Mankiller faced threats, insults, and a grueling campaign, but she and Swimmer prevailed.

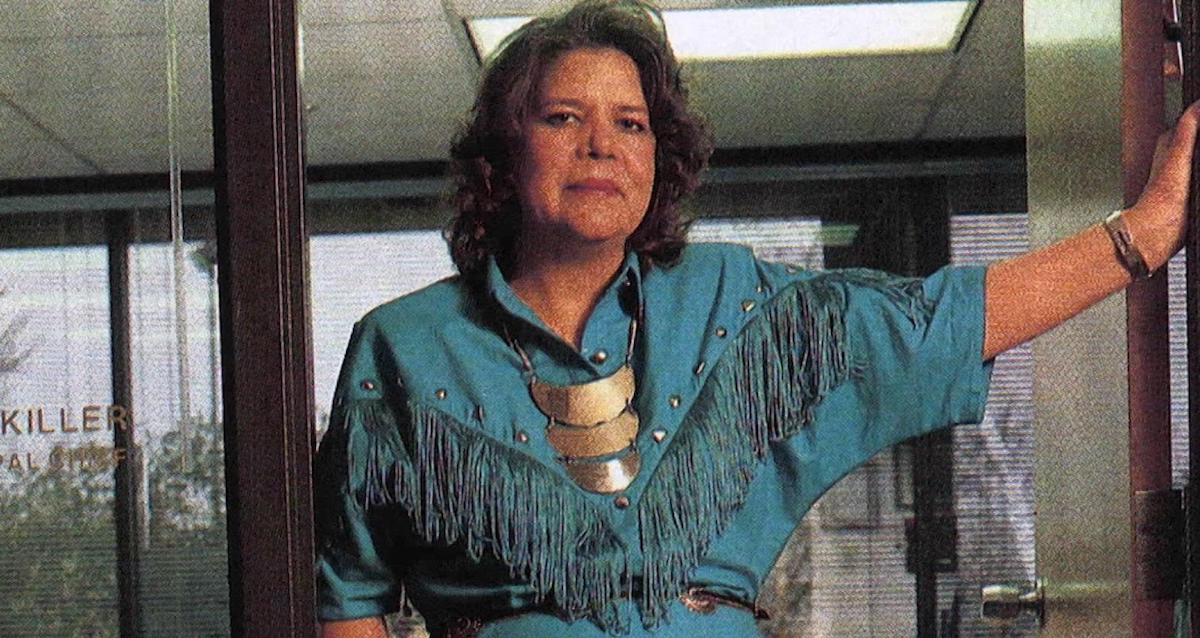

Just two years into her term as Deputy Chief, Swimmer was appointed Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs by President Ronald Reagan, leaving a vacancy. On December 5, 1985, Wilma Mankiller ascended to the office of Principal Chief, making history as the first woman to lead a major Native American tribe. It was a moment of immense significance, breaking barriers not just for the Cherokee Nation but for indigenous women everywhere.

Her ten years as Principal Chief were transformative. Mankiller championed a philosophy of self-determination, emphasizing tribal sovereignty and the need for the Cherokee Nation to control its own destiny, rather than relying solely on federal government programs. Under her leadership, the Cherokee Nation experienced remarkable growth in several key areas:

Economic Development: While the casino industry would later become a major economic engine for many tribes, Mankiller focused on diversifying the Cherokee economy through a range of enterprises, including manufacturing, tourism, and health services. She understood that economic independence was crucial for true self-determination.

Healthcare and Education: Mankiller oversaw the expansion of tribal health clinics, ensuring better access to medical care for Cherokee citizens. She also prioritized education, establishing new programs, expanding scholarships, and promoting cultural preservation through language immersion and traditional arts. Her belief was that "the most important thing is to empower people, to give them a real sense of self-worth and dignity."

Community Infrastructure: Building on her earlier work, she continued to invest in critical infrastructure projects, bringing improved housing, water systems, and roads to underserved communities within the Nation. These projects were often undertaken with the same "sweat equity" model she had championed, fostering community engagement and skill-building.

Cultural Revitalization: Mankiller understood that true strength lay in cultural identity. She actively promoted the Cherokee language, traditional stories, and ceremonies, ensuring that the next generation remained connected to their heritage. She believed that "a people without a history is like a tree without roots."

Throughout her tenure, Mankiller was known for her collaborative and consensus-building leadership style. She eschewed hierarchical structures, preferring to listen to her people, gather diverse perspectives, and build broad support for initiatives. Her approach was rooted in traditional Cherokee values of community harmony and collective decision-making. "I want to be remembered as the person who helped us restore faith in ourselves," she once stated.

Mankiller’s leadership was all the more remarkable given the profound personal challenges she faced. Her life was a testament to resilience in the face of adversity. In 1979, she was involved in a severe car accident that left her with extensive injuries, including facial paralysis and the loss of sight in one eye. Later, she battled myasthenia gravis, a debilitating neuromuscular disease, and underwent a kidney transplant. In 2010, she was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, which ultimately claimed her life. Yet, through all these trials, her dedication to her people never wavered. She continued to work, advocate, and inspire, often leading from her hospital bed.

Wilma Mankiller retired from the Principal Chief position in 1995, citing health reasons. Her departure marked the end of an era, but her legacy continued to resonate. She became a powerful voice for indigenous rights on the national and international stage, advocating at the United Nations and serving on various boards and commissions. She authored her autobiography, Mankiller: A Chief and Her People, which became a best-seller and further cemented her place as an inspirational figure.

Wilma Mankiller’s impact extends far beyond the borders of the Cherokee Nation. She shattered stereotypes about indigenous leadership and about women in power. She demonstrated that effective leadership is not about wielding authority, but about serving the community, fostering empowerment, and nurturing cultural identity. Her life story is a powerful narrative of overcoming adversity, reconnecting with heritage, and dedicating oneself to the betterment of others.

In a world still grappling with issues of social justice, equity, and self-determination, Wilma Mankiller’s vision and leadership remain profoundly relevant. She taught us that true power comes from within communities, that progress is built on collective effort, and that the strongest leaders are those who empower their people to find their own voices and forge their own paths forward. Her journey from the rural plains of Oklahoma, through the urban activism of San Francisco, and back to the heart of the Cherokee Nation, stands as an enduring beacon of hope and a testament to the transformative power of compassionate, courageous leadership.