Echoes in Stone and Mud: A Journey Through Ancient Housing Styles

From the humble mud-brick dwellings of the Fertile Crescent to the sprawling, multi-story insulae of Imperial Rome, the homes of ancient cultures were far more than mere shelters. They were silent architects of society, embodying a civilization’s values, technological prowess, environmental adaptation, and social hierarchies. To peer into these ancient abodes is to understand the heartbeat of forgotten peoples, their daily rituals, their fears, and their aspirations, etched into the very fabric of their walls.

The story of human habitation begins with necessity, but quickly evolves into an art form, a science, and a profound statement of cultural identity. What follows is a journey through time and across continents, exploring the diverse and often ingenious housing styles that defined some of the world’s most enduring civilizations.

The Cradle of Civilization: Mesopotamia and Egypt

In the fertile crescent between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the earliest urban centers blossomed, and with them, the first distinct housing styles. Mesopotamian cities like Ur and Babylon, often densely packed, saw the rise of homes predominantly constructed from mud brick. This readily available material, sun-dried or kiln-fired, was the cornerstone of their architecture. Houses typically featured flat roofs, essential for sleeping during hot summer nights and for drying goods. A central courtyard was a common feature, providing light, ventilation, and a private family space away from the dusty, crowded streets. These homes were often inward-facing, reflecting a desire for privacy and protection. The lack of enduring stone for domestic structures means much of our understanding comes from archaeological digs revealing foundations and city layouts, rather than standing homes. The fleeting nature of mud brick housing contrasts sharply with the monumental religious architecture, like the Ziggurats, which were built to last.

Just west, along the life-giving Nile, ancient Egypt developed its own distinctive approach. While the pyramids and temples speak of eternity in stone, the homes of the living were largely constructed from the same humble material as Mesopotamia: mud brick, often mixed with straw for added strength. The typical Egyptian home, whether a humble peasant’s dwelling or a wealthy official’s villa, was designed for the hot, arid climate. Flat roofs were common, and thick walls provided insulation against the relentless sun. Ventilation was crucial, often achieved through strategically placed windows and even rudimentary "wind catchers" on larger homes.

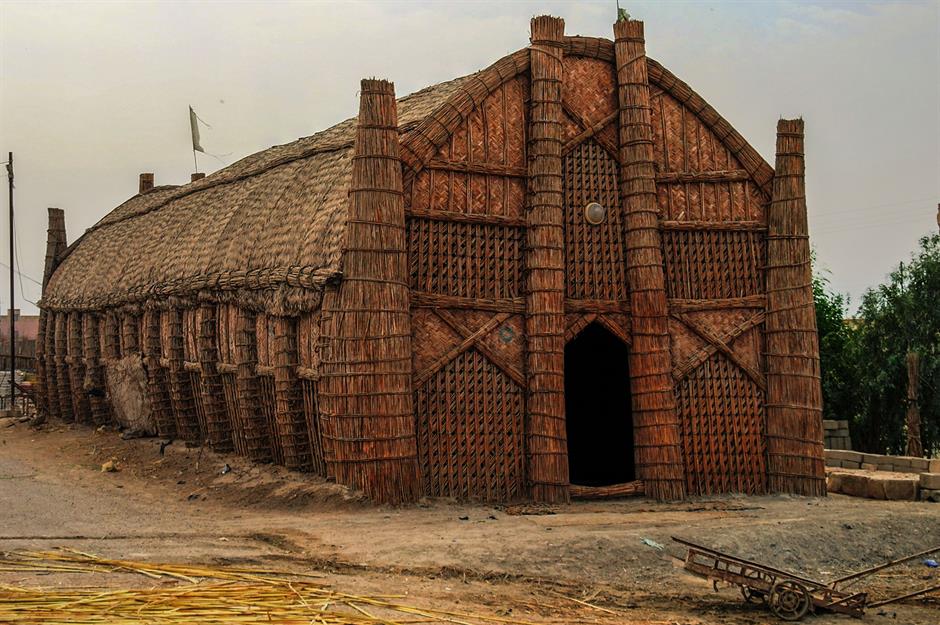

Unlike the Mesopotamians, Egyptians often incorporated reeds and papyrus into their lighter structures or as roofing elements. Peasant homes were simple, often consisting of a few rooms, while the elite enjoyed more elaborate estates with multiple courtyards, gardens, servants’ quarters, and even private baths. A fascinating aspect is the contrast between the ephemeral nature of their homes for the living, and the monumental, eternal houses for the dead (tombs). As Egyptologist Rosalie David noted, "The tomb was the permanent house of the dead, whereas the house of the living was often a temporary dwelling." This distinction underscores a fundamental aspect of Egyptian belief: life on Earth was but a prelude to the afterlife.

The Indus Valley: Urban Planning Pioneers

Moving east to the Indus Valley, civilizations like Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro (circa 2500-1900 BCE) showcased an astonishing level of urban planning and architectural standardization. Their cities were laid out on a meticulous grid system, with houses built primarily from kiln-fired bricks, a testament to their advanced technology. This made their structures far more durable than the sun-dried mud brick of their contemporaries.

Indus Valley homes were often multi-story, sometimes reaching two or three levels, and typically featured central courtyards. What truly sets them apart is their sophisticated drainage and sanitation systems. Almost every house had its own private bathing area and toilet, connected to an elaborate network of covered drains running beneath the streets – a public health infrastructure unparalleled in the ancient world until the Romans. The uniformity in house size and construction across different social strata suggests a highly organized, perhaps even egalitarian, society, or at least one with strong central authority ensuring civic order.

Aegean Splendor: Minoans and Mycenaeans

The Bronze Age Aegean gave rise to two distinct but influential cultures: the seafaring Minoans on Crete and the warlike Mycenaeans on mainland Greece. Minoan architecture, epitomized by the magnificent Palace of Knossos, reveals a sophisticated and opulent lifestyle. While the palace served as an administrative and religious center, its residential quarters, with their multi-story construction, light wells, and complex plumbing systems, offer a glimpse into the domestic grandeur. Minoan homes were often built of stone and timber, with frescoed walls depicting vibrant scenes of nature and daily life. They embraced natural light and ventilation, creating comfortable and aesthetically pleasing living spaces. The famed "Queen’s Megaron" at Knossos, with its vibrant dolphin frescoes and intricate design, highlights their artistic and architectural sophistication.

On the mainland, the Mycenaeans built heavily fortified citadels atop hills, reflecting a more militaristic society. Their homes, often within these massive "Cyclopean" walls (named for the mythical giants thought to have built them), were simpler in design but robust. The central feature was often the megaron, a large rectangular hall with a central hearth and four columns supporting a roof, which served as the heart of the home or palace. This architectural form would later influence classical Greek temple design. Mycenaean houses were constructed from rubble masonry and mud brick, with timber reinforcing the walls.

Classical Greece: Modesty and Public Life

The ancient Greeks, renowned for their philosophy, democracy, and monumental public architecture like the Parthenon, lived in surprisingly modest homes. For much of the classical period, the private dwelling was seen as secondary to public life and civic spaces. Homes were typically constructed from mud brick on stone foundations, with tiled roofs and a central courtyard (the aula or pastas) that served as the focal point for family life. Rooms were arranged around this open space, providing light and ventilation.

Wealthier homes might feature separate rooms for men (the andron) and women (the gynaeceum), rudimentary indoor plumbing, and simple mosaic floors. However, even the most affluent Greek homes lacked the ostentatious display found in other ancient civilizations. Their architecture prioritized function, privacy, and integration with the surrounding environment. As Aristotle observed in "Politics," the ideal house was one that "looks outwards toward the sun" in winter and "inwards towards the sun" in summer, showing an early understanding of passive solar design. The focus was on the polis (city-state) and its public buildings, while the home remained a private, functional space.

Imperial Rome: Engineering Marvels and Urban Density

No civilization perhaps embraced architectural innovation and diversity in housing as comprehensively as the Roman Empire. Their vast urban centers, particularly Rome itself, demanded ingenious solutions to accommodate a burgeoning population.

For the wealthy elite, the domus was the epitome of Roman domestic architecture. These single-family homes, often sprawling across city blocks, were characterized by a central atrium (an open-roofed courtyard) that collected rainwater into an impluvium (a shallow pool). Beyond the atrium lay the peristyle, a colonnaded garden that provided light, air, and a tranquil retreat. Domus walls were often adorned with elaborate frescoes, and floors with intricate mosaics, showcasing the owner’s wealth and taste. They frequently included private baths, libraries, and elaborate dining rooms. The preserved homes of Pompeii offer an unparalleled glimpse into the luxurious and detailed interiors of these Roman abodes.

For the vast majority of the Roman populace, especially in crowded cities like Rome, life was lived in insulae – multi-story apartment blocks. These were the world’s first true high-rise buildings, sometimes reaching six or seven stories, though structural integrity often suffered. Constructed from concrete and brick, insulae were a testament to Roman engineering and their need to house a massive urban population. Apartments on the lower floors were larger and more expensive, often featuring amenities like piped water. Upper floors, however, were smaller, more cramped, and less stable, prone to fire and collapse. The insulae represented the stark social stratification of Roman society, from the ground floor shopkeepers to the impoverished tenants in the perilous upper levels.

Beyond the cities, the Roman elite retreated to magnificent villae – country estates that combined agricultural production with luxurious living. These often included elaborate gardens, private bathhouses (featuring hypocausts for underfloor heating), and even private amphitheaters, showcasing the ultimate in Roman comfort and engineering.

Mesoamerica: Harmony with Cosmos and Nature

Across the Atlantic, the ancient civilizations of Mesoamerica – the Maya, Aztec, and Inca – developed housing styles intimately connected to their spiritual beliefs, astronomical knowledge, and challenging environments.

The Maya, known for their towering pyramid temples and sophisticated calendar, built homes primarily from stone, adobe (sun-dried brick), and timber, with thatched roofs made from palm leaves. While their grandest structures were ceremonial, their residential compounds often reflected a similar reverence for order and the cosmos. Houses were typically arranged around central courtyards, sometimes elevated on platforms to protect against floods and signify status. The elaborate stone carvings and frescoes found in their temples suggest a similar aesthetic would have adorned the homes of the elite.

The Aztecs, who built the magnificent city of Tenochtitlan on a lake, utilized adobe, stone, and wood, constructing homes on raised platforms or chinampas (floating gardens) to cope with the watery environment. Their houses, often brightly painted, featured flat roofs that served as additional living space and gardens. The imperial city itself was a marvel of urban planning, with canals serving as streets and grand palaces built around courtyards.

In the Andes, the Inca perfected the art of stone masonry, crafting structures with unparalleled precision, fitting stones together so tightly that no mortar was needed. Their homes, often built on steep mountain terraces, were typically rectangular, single-story structures with thatched roofs. The ingenuity of their terraced farming and complex road networks extended to their residential planning, with entire villages built into the challenging terrain, often designed to withstand earthquakes. Machu Picchu, while a royal estate or sacred retreat, showcases the pinnacle of Inca domestic and civic architecture, with its perfectly fitted stone walls and strategic placement within the landscape.

Ancient China: Order, Hierarchy, and Feng Shui

Early Chinese housing, particularly during the Shang and Zhou dynasties, saw the development of distinctive architectural principles that would influence centuries of design. Homes were predominantly constructed from rammed earth, wood, and later, brick. The prevailing layout was the courtyard house (siheyuan), a complex of buildings arranged around one or more central courtyards. This design reflected the importance of family, hierarchy, and privacy.

The orientation of the house was crucial, often dictated by principles that would later evolve into feng shui, emphasizing harmony with the natural environment and cosmic forces. The main hall, usually facing south for optimal sunlight and protection from northern winds, housed the most important family members or served as a reception area. Bedrooms and other functional rooms branched off from the courtyards. Tiled roofs, often with intricate ornamentation, became a hallmark of Chinese architecture, signaling status and wealth. While the Forbidden City represents the apex of imperial architecture, its fundamental principles of courtyard design, axial symmetry, and hierarchical arrangement were scaled down and replicated in the homes of the common people, reflecting a deeply ingrained cultural order.

Conclusion: A Mirror to Humanity

From the earliest mud-brick shelters to the engineered wonders of Rome, the housing styles of ancient cultures tell a profound story. They speak of human ingenuity in adapting to diverse climates, mastering available materials, and innovating construction techniques. They reveal the intricate social structures, the economic disparities, and the prevailing belief systems of societies long past.

Whether it was the emphasis on civic order in the Indus Valley, the spiritual connection to the cosmos in Mesoamerica, or the pragmatic adaptation to urban density in Rome, each dwelling was a microcosm of its culture. These silent architects, though often reduced to foundations and fragments, continue to speak volumes, reminding us that even the most fundamental human need for shelter can be transformed into a powerful expression of identity, aspiration, and the enduring human spirit. They are not merely ruins; they are echoes of lives lived, dreams dreamt, and civilizations built, etched forever in stone and mud.