Seeds of Civilization: Unearthing the First Domesticated Plants of the Americas

Thousands of years ago, a silent revolution took root across the Americas, long before the arrival of European explorers. It was a transformation driven by human ingenuity and observation, as ancient peoples began to coax sustenance from the wild, selectively breeding plants to better serve their needs. This profound shift from nomadic hunter-gathering to settled agriculture laid the groundwork for complex societies, sprawling cities, and enduring cultural traditions, forever altering the trajectory of human history in the Western Hemisphere.

The story of the first domesticated plants in the Americas is a rich tapestry woven with threads of genetic research, archaeological discovery, and the invaluable knowledge of Indigenous communities. Unlike the Old World, where a relatively small suite of cereals like wheat and barley dominated early agriculture, the Americas saw a diverse array of plants domesticated across distinct ecological zones, each contributing uniquely to the diet and culture of its people.

Mesoamerica: The Cradle of Maize and Its Companions

Perhaps no plant embodies this transformation more dramatically than maize (corn). Today, it is a global staple, but its origins lie in the Balsas River Valley of south-central Mexico. Here, around 9,000 years ago, ancient farmers began the painstaking process of transforming a humble wild grass called teosinte into the plump, kernel-rich cobs we recognize today.

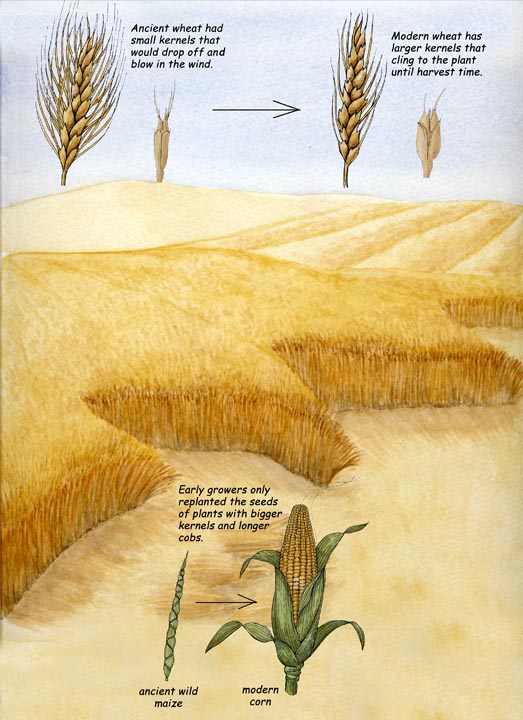

Teosinte is a far cry from modern corn. Its kernels are small, few, and encased in a hard fruitcase, making them difficult to access and consume. Yet, through generations of careful selection for traits like larger kernels, softer glumes, and kernels that remained attached to the cob, Indigenous cultivators engineered one of humanity’s most successful crops. Genetic studies, notably those by Dr. John Doebele and Dr. George Beadle, conclusively demonstrated the direct lineage from teosinte to maize, a triumph of ancient bioengineering.

The domestication of maize was not a singular event but a gradual process. Early archaeological evidence from sites like Guila Naquitz Cave in Oaxaca, Mexico, shows some of the earliest signs of maize cultivation, along with its frequent companions: squash and beans.

Squash (Cucurbita species) often predates maize in the archaeological record, with evidence of its domestication dating back perhaps 10,000 years ago in Mesoamerica. Wild gourds and squashes, initially valued for their hard rinds as containers, were gradually selected for their edible flesh and seeds. Species like Cucurbita pepo, which includes pumpkins and many summer squashes, were among the first to be cultivated, providing a crucial source of carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals. Their robust nature and ability to store well made them invaluable to early agricultural communities.

Beans (Phaseolus species), particularly common beans, are another Mesoamerican marvel. Domesticated around 8,000 years ago, they form a perfect nutritional synergy with maize and squash, famously known as the "Three Sisters" agricultural system. Maize provides a stalk for beans to climb, beans fix nitrogen in the soil, enriching it for all three, and squash leaves shade the ground, retaining moisture and suppressing weeds. Nutritionally, the amino acids lacking in maize are abundant in beans, providing a complete protein source when consumed together – a testament to the sophisticated understanding of agriculture held by ancient American peoples.

Adding a fiery kick to this ancient diet were chili peppers (Capsicum species). Evidence from Ecuador suggests domestication as early as 6,100 years ago, making them one of the oldest domesticated plants in the Americas. Beyond their flavor, chilies also possess antimicrobial properties, which would have been beneficial for food preservation in pre-refrigeration times.

Other important crops from Mesoamerica include avocado, cacao (the source of chocolate), and cotton. Avocado, domesticated around 8,000 years ago, offered a rich source of healthy fats. Cacao, appearing in the archaeological record by 3,900 years ago, was not just a beverage but a highly valued commodity, even used as currency by some Mesoamerican civilizations. Cotton, crucial for textiles, also saw early domestication, with some of the oldest evidence found in Peru, indicating distinct domestication events.

The Andean Highlands: A Different Palette of Staples

While Mesoamerica gave the world maize, the rugged, high-altitude landscapes of the Andes Mountains were the birthplace of another global staple: the potato (Solanum tuberosum). Originating in the region around Lake Titicaca, on the border of modern-day Peru and Bolivia, potatoes were domesticated around 8,000 to 10,000 years ago.

The genetic diversity of Andean potatoes is staggering, with thousands of varieties, each adapted to specific microclimates and possessing unique flavors, textures, and colors. This diversity was a crucial buffer against crop failure, ensuring food security in a challenging environment. Beyond their caloric value, potatoes were central to Andean culture, forming the basis of advanced agricultural techniques like terracing and the creation of chuño – freeze-dried potatoes that could be stored for years, a brilliant example of ancient food preservation.

Alongside potatoes, the Andes also saw the domestication of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) and amaranth (Amaranthus species), often termed "pseudo-cereals." These highly nutritious grains, rich in protein, fiber, and essential amino acids, thrived in the high-altitude conditions where conventional cereals struggled. Quinoa, with evidence of domestication dating back 5,000-7,000 years ago, was a sacred crop to the Inca, who called it "the mother of all grains." Amaranth, similarly ancient, was also a significant food source and held ritualistic importance in both Andean and Mesoamerican cultures.

The Amazon and Beyond: Manioc, Peanuts, and More

Venturing into the lush, humid environments of the Amazon basin reveals another set of vital domesticates, most notably manioc (Manihot esculenta), also known as cassava or yuca. This starchy root crop, domesticated around 8,000-10,000 years ago, became a staple for millions across South America. Wild manioc contains toxic levels of cyanide, requiring sophisticated processing techniques like grating, pressing, and heating to make it edible – a remarkable feat of ancient ethnobotany. The ingenuity involved in detoxifying manioc highlights the deep scientific knowledge possessed by Amazonian peoples.

Other significant crops from South America include peanuts (Arachis hypogaea), domesticated around 7,600 years ago in Bolivia, offering a rich source of protein and oil. Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), originating in Central or South America around 8,000-10,000 years ago, also became a widespread staple, known for its high caloric value and adaptability. Its journey across the Pacific to Polynesia remains a fascinating testament to ancient transoceanic contact.

Further north, in what is now the United States, Indigenous peoples domesticated crops like sunflower (Helianthus annuus) for its seeds and oil, and various gourds and marsh elder. These regional domestications underscore the pervasive and independent development of agriculture across the continent.

The Impact and Enduring Legacy

The ripple effect of plant domestication was immense. It allowed human populations to grow exponentially, as a smaller area of land could support more people. This newfound stability led to sedentism, the establishment of permanent villages, and subsequently, the development of more complex social structures, specialized labor, and monumental architecture. The Olmec, Maya, Aztec, Inca, and countless other civilizations were built upon the foundation of these cultivated plants.

The agricultural revolution in the Americas also had a profound global impact, particularly after the Columbian Exchange. Crops like maize, potatoes, tomatoes, chili peppers, squash, and beans were introduced to the Old World, transforming diets, driving population growth, and contributing significantly to the global food system. It is difficult to imagine Italian cuisine without the tomato or Irish history without the potato, yet both are American gifts to the world.

Today, the study of these first domesticated plants continues to yield new insights. Modern genetic techniques allow scientists to trace the evolutionary pathways of these crops with unprecedented detail, confirming archaeological findings and shedding light on the precise mechanisms of domestication. This research not only helps us understand our past but also informs future efforts in sustainable agriculture and food security, particularly in the face of climate change.

The story of the first domesticated plants in the Americas is a testament to the profound ecological understanding, patience, and innovative spirit of ancient peoples. It is a legacy etched in the genetic code of our food, a quiet revolution that continues to nourish billions and reminds us of humanity’s enduring connection to the earth and its bountiful offerings. From humble wild grasses and tubers, a new world was cultivated, proving that some of the most powerful transformations begin with a single seed.